Researchers using the laser mapping technology Lidar have revealed a vast, urban complex of more than 6,000 earthen platforms in Ecuador’s Upano Valley, according to research published in the journal Science last week. High in the foothills of the Andes, this is the Amazon’s earliest and largest example of agrarian urban settlements.

One of the primary authors of the study, French archaeologist Stéphen Rostain, who has spent four decades studying Amazonian heritage, says that while his fieldwork determined there were hundreds of mounds, the Lidar scans revealed that there were thousands.

“These were huge earthworks made by Indigenous people,” says Rostain, who directs investigations at France’s National Center for Scientific Research. The mounds, he says, were a series of complexes inhabited by upwards of 10,000 people and containing housing and “square low plazas for community activities enclosed by peripheral platforms”, as well as tiered gardens.In between the mounds were agricultural fields that had been drained to grow crops such as maize, beans, sweet potatoes and yucca.

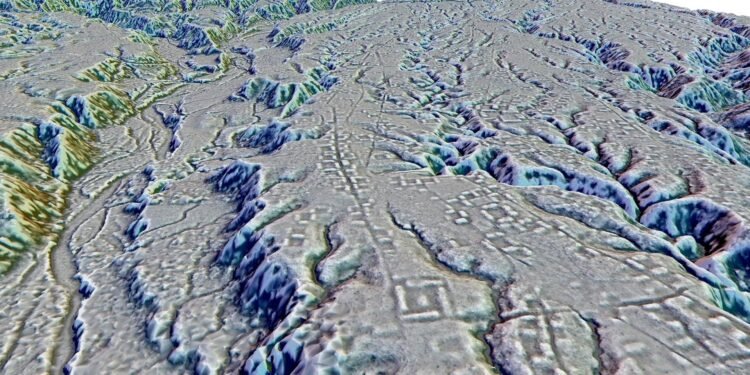

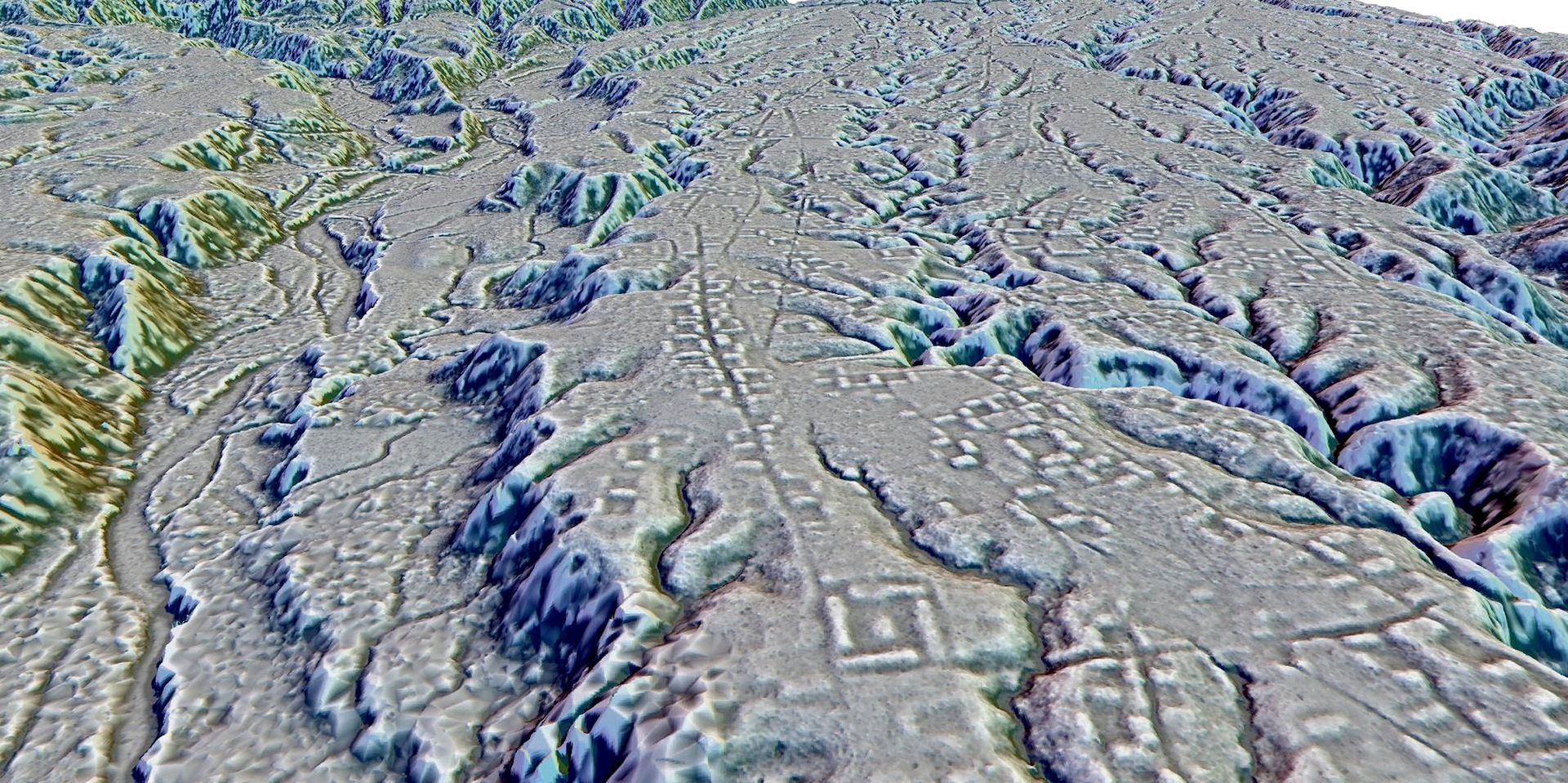

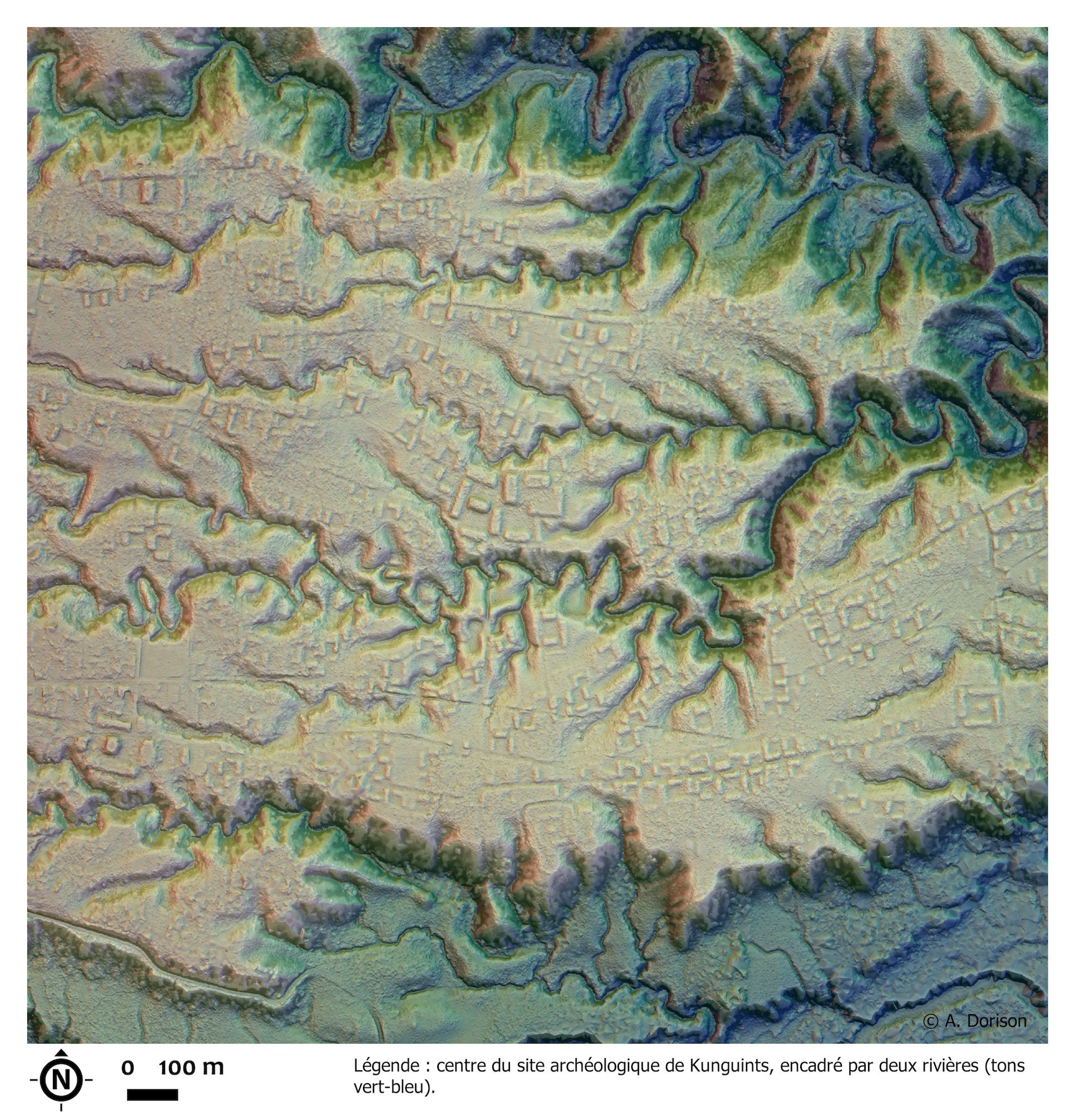

Kunguints site, Upano Valley, Ecuador. Complexes of rectangular platforms are arranged around low squares and distributed along wide dug streets Image: Lidar, A. Dorison and S. Rostain

The discovery is significant not only for its scale, he says, but also because it puts paid to prevalent “racist and colonial attitudes toward Indigenous peoples in Latin America”. While many Latin American countries celebrate their Incan heritage, he notes, they often ignore their Amazonian heritage.

The findings—the culmination of two decades of his fieldwork—contradict the “prevailing idea that Indigenous peoples in the area were only nomadic hunters and gatherers”, Rostain adds. This discovery, he says, has “changed the paradigm of environmental determinism”. When Rostain began his fieldwork in French Guyana in the 1980s, he found “thousands of mounds in coastal swamps—but no one believed that Indigenous people had made these mounds”.

Some of the Upano Valley mounds have already been destroyed by new settlements set up by cattle farmers. The challenge now, he says, is to prevent further destruction of this “treasured” archaeological site.

“It was a special valley because it was never really colonised,” Rostain says. The territory of the Aents Chicham was largely untouched until the 1970s, he adds, with “no roads and no communications—like a lost valley”. The area was occupied by the mound builders from 2500BCE to 600CE. “After that, no one lived there for two to three centuries. We don’t know what happened, but it could have been volcanic activity, climate or cultural changes.” Currently, he says, there are no Indigenous people living there, only non-native settlers.

Complex of rectangular earth platforms of the Nijiamanch site along the cliff edge of the Upano riverbed, Ecuador Image: Stéphen Rostain

But in an interview with The Art Newspaper, Manari Ushigua, an Indigenous leader from the Sápara Nation, says there have been “stories about ancient cities for centuries in our communities”. They were part of ancient Amazonian civilisations, he explains, that disappeared because of climate change or what he terms a cambio del sol (or “sun change”) in line with ancient Mayan calendars. “These were civilisations” are, he says, “on a par with European ones”.

A self-described “protector of the forest” and healer, Ushigua co-founded the Naku Centre, which creates an economic model in the Amazon based around cultural and forest preservation.

“These are sacred sites and their preservation is important not just for our communities but for all of humanity,” Ushigua says. “They contain secrets about climate change that can help not only the fragile Amazonian environment but the whole planet. We are suffering from the effects of rampant development and environmental destruction everywhere—but if we look to the jungle and these ancient places we can learn a lot.” There are many other ancient sites hidden underground, he says, their whereabouts known only to Indigenous peoples.

Kunguints site, Upano Valley, Ecuador. Dug streets crosse the urban area where they are bordered by complexes of rectangular platforms arranged around low squares Image: Lidar, A. Dorison and S. Rostain

According to Rostain, a priest named Juan Botaso arrived in the 1970s and noticed the mounds. He showed another priest, an amateur archaeologist named Pedro Porras, who “made a crude excavation and published a paper, whose only merit was to reveal the existence of the mounds in the rainforest”. Andean countries—including Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador—“are fascinated by their mountains and coast but not the Amazon”, Rostain says. “This is due to a colonial, racist mentality that natives of the Amazon are ‘savages’ incapable of building anything sophisticated.”

Rostain began working in Ecuador in 1996 and in the Upano Valley in 2015, the same year the government mandated a private company to employ the Lidar technology in surveying the region. Due to bureaucratic snafus, the survey was only released in 2020. Rostain spent another two years making a detailed study with a colleague.

Unfortunately, he says, the site will be destroyed unless there is international intervention. He adds, “The government doesn’t care about Amazonian heritage. It’s just a place for resource extraction.”

One hopeful note is that the recent discovery, he says, has instilled a sense of pride in Ecuadorian patrimony. “All my friends and family were so pleased that Ecuador was in the news not for narco-gang problems and violence—but for a huge archaeological discovery, “Rostain, who is married to an Ecuadorian woman, says. “That alone is a small victory.”