Africa’s biggest football festival – the men’s Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) – is happening in Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa. People from across the continent are following the tournament closely, sitting close to their televisions and talking about it on social media.

Everything seems set: the host nation spent over $1 billion to build four new stadiums along with roads and hospitals for this competition. Some of football’s most famous athletes will be participating, and it is winter in Europe, so they aren’t splitting attention with any other contest. The winner’s prize money will be 40% higher than their predecessor’s — a new record. On the opening day, thousands of supporters flooded the streets of Abidjan to the town of Ebimpé. But the stadiums, where all the action is, are mostly empty, and not for the first time.

Previous tournaments in Ghana, Angola, South Africa, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Cameroon have had the same story. Some matches, especially those involving Senegal, Mali, Benin, Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire, turn out livelier than others because of organised supporters’ groups, usually including bands which play throughout the games. But these groups don’t come for free. Federations, governments or sponsors often bankroll these 500-1,500-strong performers to show up at games. Regular citizens, who have no incentives other than having a good time, are hardly present.

Football tournaments are one of the most popular methods of attracting tourists. It’s why people compete for the right to host the World Cup. But these empty seats show how much the continent misses out on intra-African tourism.

Why won’t people show up?

The short answer is that getting to AFCON is too difficult or expensive for many Africans. Officially, tickets cost 5000 FCFA (about $8) for Category 3, 10000 FCFA (about $16) for Category 2 and 15000 FCFA (about $24). And the prices go up as the competition progresses. These prices cut out at least 85% of Africans who live on less than $5.50 daily.

Most participating countries are battling high inflation and currency devaluation, so their middle class is depleting. Nigeria, for instance, just had its worst year for the naira in 2023, and inflation is now near 30%. Ghana’s inflation also went as high as 43% last year. Egyptian authorities have implemented three sharp devaluations of the currency since early 2022. The IMF predicted Equatorial Guinea to fall back into a recession in 2023.

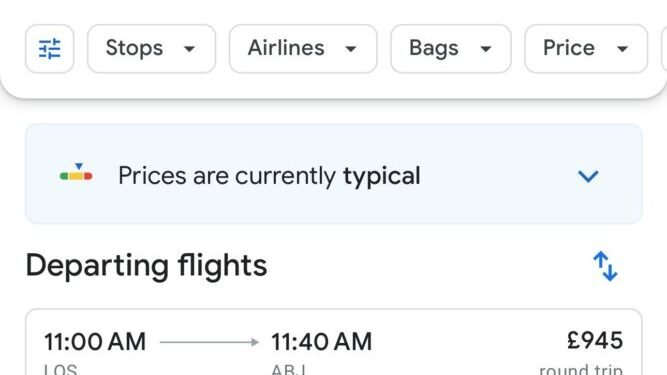

Also, intra-African commute is burdensome. Flying from Berlin, the capital of Germany, to Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, might cost you around $150 for a direct flight lasting under three hours. Meanwhile, travelling a similar distance between Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city, could cost between $500 and $850, often involving at least one layover and taking as much as 20 hours. A flight from London to Warsaw, which spans about 2hrs 15mins for a non-stop flight, costs £30. But if a Nigerian wanted to travel to Côte d’Ivoire for the tournament, they would spend £945 on a 1hr 40mins non-stop flight.

Taxes, statutory charges and levies, high jet fuel costs, airport taxes, and ground handling fees are some of the reasons airfare costs are so expensive. This article by Dorine Reinstein also shows that Africa-based airlines struggle with economies of scale because there’s not enough demand for intra-African travel. It’s the proverbial chicken and the egg situation. Little demand is leading to high prices and vice versa.