Nonfiction

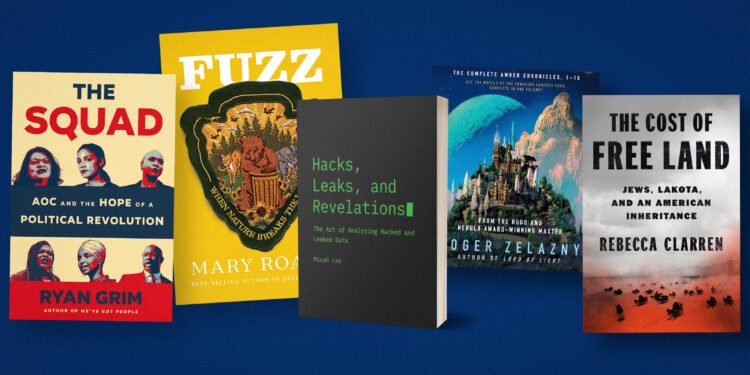

“The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance,” Rebecca Clarren

That Rebecca Clarren’s Jewish ancestors escaped antisemitic persecution in Russia, received free land from the U.S. government at the turn of the 20th century, and settled in South Dakota is a foundational part of her family lore. What went unquestioned over the years is whether they had any right to that land in the first place. In this timely and unflinching book, Clarren investigates how her family benefited from genocidal U.S. policies against the Lakota and other Indigenous peoples. Crucially, as a beneficiary of stolen land, Clarren also consults with her rabbi and Indigenous elders about how to begin to repair those harms. That yearslong process resulted in, among other things, a reparations project to help “return Indian lands in the Black Hills (He Sapa) to Indian ownership and control.” As Israel rains bombs on Gaza, it’s hard to read this book and not reflect on the ongoing consequences of land theft, whether in the United States or in Palestine. — Maryam Saleh

“Camino a la Fosa Común (Journey to the Common Grave),” Memo Bautista

The concept of a “common grave” conjures an image of large, World War II-type trenches, where piles of unidentified bodies are discarded and buried. But in 21st-century Mexico, common grave burials are a strict process. Due to the high levels of violence, with tens of thousands of people disappeared, common graves in Mexico are heavily guarded and meticulously organized, in case authorities need to access remains for an investigation. It is a grim reminder of how the Mexican drug war violence persists, violence typically perceived through faceless statistics.

Journalist Memo Bautista’s Spanish-language book, difficult to find outside of Mexico City, gives life to the numbers of dead in Mexico, not just for those who have died of drug war violence, but also ordinary working-class Mexicans.

As Bautista writes in his introduction, many of us have an image of how we want our own death to look like: We’ll spend a day eating our favorite foods, playing our favorite games, surrounded by our favorite people, and then pass away peacefully in our sleep. Often, that is not the case. Bautista’s collection of nonfiction stories chronicles how the living deal with the aftermath of untimely deaths: from the sanitation officials who clean the Mexico City subway after someone is struck, to the grieving mother whose teenage son is killed in a rural community’s agrarian conflict, to the young workers embalming lifeless bodies in Mexico City.

Bautista’s eponymous story is about a charming and complicated homeless man, Escalera, who Bautista follows for a period of years. After dying of hypothermia in Mexico City’s historic center, Escalera’s journey ends in the “common grave.” — José Olivares

“Hat Box: The Collected Lyrics of Stephen Sondheim,” Stephen Sondheim

We all know Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. At the bottom, there are physiological needs, such as food and shelter. Then there are psychological needs, including love, societal prestige, and self-actualization. Finally, at the very top, there is the need for the musicals of Stephen Sondheim.

This is only partly a joke. Sondheim’s work is generally for people whose other needs have been met. But if they have — wow, it is going to make your life exquisitely vibrant. You’ve been to the shows. You’ve bought the albums. You (I) have delivered your monologue accepting an imaginary Special Lifetime Achievement Tony Award for Private Sondheim Shower Interpretation. Next, you need “Hat Box.” It’s a two-volume memoir by Sondheim, except it’s purely about his work, and includes essentially all the lyrics he wrote through 2011, plus all the detail you could ever wish about how this spectacular, subtle artist made his spectacular, subtle art. — Jon Schwarz

“Innocent Until Proven Muslim: Islamophobia, the War on Terror, and the Muslim Experience Since 9/11,” Maha Hilal

In quiet moments, photographs I’ve seen from Getty Images and social media race behind my eyes in vivid detail, showcasing an unstoppable flow of atrocities in Gaza. How is it possible that Israel’s actions still maintain such fervent and radical support? How is it possible the United States continues to send endless weapons and military support to their genocidal campaign in Palestine in defiance of global protest? In thinking about how the lives of civilians — nearly 10,000 children — can matter so little, I have been rereading my friend Maha Hilal’s brilliant book “Innocent Until Proven Muslim.”

Israel’s rampage in the wake of an act of shocking violence on its own homeland feels like a repeating, almost too clearly, of America’s actions in the wake of 9/11. I wish I was shocked — but I’m not. I’ve spent my adult life thinking about the long shadow of the “war on terror.” This genocide in Gaza seems to be the logical extension of the demonization and dehumanization of Muslims that the U.S. has so intentionally perfected. Hilal’s book, a devastating exposé of how we’ve ended up here, at the very least provides a path forward. With meticulously researched examples, Hilal shows exactly how three administrations since 9/11 have painted Muslims as inherently violent at home and abroad. She weaves through American policy from the Patriot Act to CIA torture, Guantánamo Bay, FBI entrapment cases, and beyond, challenging readers to question the narratives perpetuated by policymakers and media that have brought injustice and indignity for decades. Her final radical argument that the very framework of the “war on terror” must be abolished is a powerful antidote to the injustice we feel today. — Elise Swain

“Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World,” Malcolm Harris

It’s a history of a small town. Of the Bay Area. Of a state. Of the American West. Of America. Of the West. It’s a history of empire, of conquest and genocide, of war-making and profiteering, of racism and eugenics, of moral bankruptcy and giant returns on investment. Malcolm Harris can be a very funny writer, but he isn’t kidding around when he called his latest book “Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.” I expected the tony suburb to be an avatar of all the things Harris wanted to cover, but it’s remarkable how much Palo Alto is actually a central player in American and world history. Colonial extractive industries? It’s in there. The primacy of railroads? Early avionics in the world wars? Privatization of virtually every public function? Computers? Check, check, check, and of course! Want a framework where the awesome, genocidal power of social media makes perfect sense? It’s Palo Alto.

Books that present clever unifying theories, especially when they qualify as doorstoppers, can end up being forced and fraudulent (see: Malcolm Gladwell) or, perhaps worse still, boring laundry lists of disparate facts and ideas that fail to come together. Harris, though, is an engaging writer, and the theme works so staggeringly well that “Palo Alto” holds attention and holds together. The results are frightening. Palo Alto isn’t just a town that touches our collective history; it’s one that has grabbed on to it, slaps it around, and won’t let go until it squeezes every last breath and penny out of us. — Ali Gharib

“The Living,” Tsurisaki Kiyotaka

Tsurisaki Kiyotaka is a photographer of human corpses: “They are the only subjects I want to photograph — this is my personal dogma.” This is a fact, well, beaten to death with prior titles like “The Dead,” “Death,” and “Danse Macabre to the Hardcore Works,” as well as via documentary films like “Orozco the Embalmer.” However, Kiyotaka notes his situation has at times required him to “engage in other photography to financially support my passion of corpse photography — in short, I have engaged in photojournalism, or at least a good imitation thereof.”

The outcome of life constructed as fiscal requisite for the support of death is here manifested in nearly 200 photos of protests in Ramallah, West Bank; festivals in India and Thailand; Ukraine in 2022; the aftermath of an earthquake in Japan — these and more, coalescing in a dizzying array of approaches to the living as existing to sustain the dead. As Paul Virilio once succinctly summarized, “When you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.” “The Living” extends this sensory sentiment by visually augmenting the miasma emanating from all manner of circuitry frying the world (crypto, artificial intelligence, or whatever is the current flavor of the month at your eschatological creamery). The synesthetic boundary-blurring that Kiyotaka manages to achieve here allows you to smell the searing with your eyes and cry with your fists. — Nikita Mazurov

“Sir Vidia’s Shadow: A Friendship Across Five Continents,” Paul Theroux

This is one of the best books I’ve read about friendship and particularly a friendship gone awry. It is hilarious, insightful, and timeless despite being written many years ago, and I recommend it to anyone who enjoys good writing. — Murtaza Hussain

“Hacks, Leaks, and Revelations: The Art of Analyzing Hacked and Leaked Data,” Micah Lee

Have you ever thought it might be fun to learn how to dig through troves of hacked law enforcement documents, or decipher leaked chat logs from Russian ransomware gangs, or analyze metadata from videos of the January 6 attack? And, once you find the juicy bits, publish your findings and change the world?

I just wrote a book that teaches journalists, researchers, and activists exactly how to do this! It will be released on January 9, but it ships right now if you order it directly from the publisher — and you can get 25 percent off using the discount code INTERCEPT25, valid until January 15.

No prior technical or programming experience is required. All you need is a laptop, an internet connection, and a desire to learn new skills. The book is incredibly hands-on, it uses real datasets as examples (you download them and analyze as you read), and it’s crammed full of anecdotes from the trenches of 21st-century investigative journalism. — Micah Lee

“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” Rebecca Skloot

I finished this book in about two days; I couldn’t put it down. This incredibly well-researched, engrossing, and often painful book is about more than Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cervical cancer cells were taken and used without her consent and led to huge strides in modern medicine, like the creation of vaccines for polio and HPV. It also tells the story of her children, her doctors, and her family’s fight to learn about just what happened to her cells after her death (they were never informed that her cells were being used and only found out decades later after speaking with a friend who worked at the National Cancer Institute).

Through interviews with Lacks’s husband, cousins, and friends, Rebecca Skloot paints a vivid picture of her life — and helps her family get closure after years of exploitation from researchers, scammers, and journalists. It’s a gut-wrenching read: The section where Skloot and Lacks’s daughter Deborah discover the truth about what happened to Deborah’s older sister Elsie, who was institutionalized when she was 10 and died five years later, will haunt me for a very long time. But there are also moments of beauty, like when Deborah and her brother Zakariyya see their mother’s cells for the first time. Equal parts scientific and narrative, this story is told with a lot of care and will sweep you in. — Skyler Aikerson

“Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon,” Michael Lewis

As one of the many spectators enthralled at the abrupt fall from grace of the crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried, I was happy to learn that he would also be the subject of Michael Lewis’s next book. But it wasn’t until I read the New Yorker’s review that I knew this one would jump to the top of my pile. Since the book published a month before the eventual verdict in federal court, I wanted to know how Lewis’s “contrarian bet” would stand up to the coming headlines.

I don’t agree with the take that Lewis “staked his reputation” on his assessment of SBF. He chose to publish shortly before history would determine whether he was “right” or “wrong” because, I like to think, he knew his work would help people see beyond whatever headline announced the news. In the end (no spoilers), the fact that Lewis came to a more nuanced answer to the question of SBF’s guilt than a federal jury did helps remind us all what a reporter’s job is: not to proclaim the guilt or innocence of their subject, but to tell as much of the story as possible and let readers decide where they stand. I, for one, came away with a much more layered understanding of the case than any of the many articles written about it had given me before. — Greg Emerson

“Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law,” Mary Roach

Migrating elephants and jaywalking moose and dumpster-diving bears, oh my! Mary Roach combines wildlife biology, human behavior, and consistent humor to answer the age-old question: “How does that pigeon know how to wait until the last second to fly away before it gets hit by my car?” If you love wildlife, sometimes like people, and are interested in how we can improve the path to coexistence, you won’t be disappointed with “Fuzz.” — Casey Quirke

“The Squad: AOC and the Hope of a Political Revolution,” Ryan Grim

I find myself imagining a reader in the year 2100, studying the history of the 21st century and how the world finally came together, begrudgingly and in half measures, to keep global temperatures down. Perhaps the reader is a student of the booming industry of bioengineering tasked with populating the former state of Ohio with robotic birds. And they wonder to themselves, “How did it all happen? Where were the people pushing for action in, like, 2019?” Their personal algorithmic device will immediately conjure Ryan Grim’s “The Squad: AOC and the Hope of a Political Revolution,” which covers not only Congress but also the Sunrise Movement and the conception and evolution of the Green New Deal. Unless, that is, the climate movement fails. In that case, Grim’s book will explain how the human race doomed itself to visiting aliens in a year unfathomable to man. — Nausicaa Renner

Fiction

“This Thing Between Us,” Gus Moreno

If you love smart horror, but you’re tired of smart horror’s requisite ghosts as metaphors for trauma, then this debut novel about a married couple terrorized by their Amazon Echo is for you. About 20 pages in, it springs into one of the most ferocious gallops I’ve ever read, dragging the reader across horror genres, state lines, and borders between worlds. A relentless nightmare that never feels gratuitous, even as it wraps its tendrils around you. I read it in a day, but I still haven’t shaken it off. Moreno’s future is bright: You can tell from the long shadow it casts over the world he made. — Anthony Smith

“The Chronicles of Amber,” Roger Zelazny

In this 10-book series, Roger Zelazny artfully spins a mesmerizing tale spanning infinite worlds, where readers are transported to the realms of Amber and Chaos from which all other worlds originate as mere shadows. Through multifaceted characters and detailed narratives, Zelazny shapes a sprawling mythology exploring identity, power, manipulation, and destiny against captivating fantasy backdrops. It certainly lives up to its reputation as one of the most revered fantasy series of all time. Opting for the print version? Be forewarned about its tangible heft. — Kate Miller

“The Bee Sting,” Paul Murray

I’ve been waiting for new work from Irish novelist Paul Murray ever since stumbling across “Skippy Dies” in a free book pile in southern Turkey over a decade ago, and was not surprised that his new novel, “The Bee Sting,” was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. It’s an immersive portrait of a family that meanders through each member’s lived experience so closely that you feel like you know them intimately, and yet there are surprises throughout as Murray reveals the narratives we tell ourselves in order to survive. The novel opens with the family’s financial troubles, but they quickly become subsumed by psychological trauma, academic stress, repressed sexuality, blackmail, internet stalkers, substance abuse, and climate change. It’s also propulsive and very, very funny. — Celine Piser

“Indelicacy,” Amina Cain

In a slim 158 pages, Amina Cain deftly weaves together a story about vocation, pleasure, gendered labor, restlessness, creativity under capitalism, jealousy, and desire. Whip-smart and beautifully wrought, “Indelicacy” is an eminently readable novella, an instant classic that you’ll want to revisit again and again. — Schuyler Mitchell

“The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray,” Jorge Amado

This 1959 novella by imprisoned, exiled, censored, and beloved Brazilian author Jorge Amado is even funnier than its translated title teases. “When a man dies he is reintegrated into his most authentic respectability, even having committed the maddest acts when he was alive” is what the dead man’s blood relations have long been waiting for. Unlike Henry Kissinger, Joaquim Soares da Cunha did not commit war crimes — just the unspeakable middle-class transgression of embarrassing his family. His body now cold (and controllable), they’re eager to impose their will and revise the narrative of the retired civil servant who disowned them, at the age of 50, to become Quincas Water-Bray, “the king of the tramps of Bahia … boozer in chief of Salvador … tatterdemalion philosopher of the market dock … senator of honky-tonks … patriarch of the red-light district.” His friends, his found family, refuse to let his memory be buried by hypocritical propriety. The boatloads of spilled cachaça and a few piquant whiffs of magical realism gave me a contact high. Most strangely, lo and retold, this Bahian tale inspired an American movie called “Weekend at Bernie’s.” — Nara Shin