There are many art historical references seemingly embedded within the work of Matthew Wong, the self-taught Canadian painter who died tragically by suicide five years ago, aged 35, just as he was beginning to draw widespread acclaim. There is Peter Doig and Edvard Munch’s tender isolation, Henri Matisse’s love for expansive blocks of colour, and Wu Guanzhong’s radical handling of perspective and composition—to name but a handful.

Few artists, however, appear to hold as great a connection to Wong’s work as Vincent van Gogh, who captured through swirling thick brushstrokes and an intense colour palette a similarly rich sense of emotion and spiritual feeling. Next month, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam will put on an exhibition placing these two artists side by side, charting Wong’s fascination with his Dutch Modernist predecessor and celebrating both their artistic and “personal” relationship, says its curator Joost van der Hoeven.

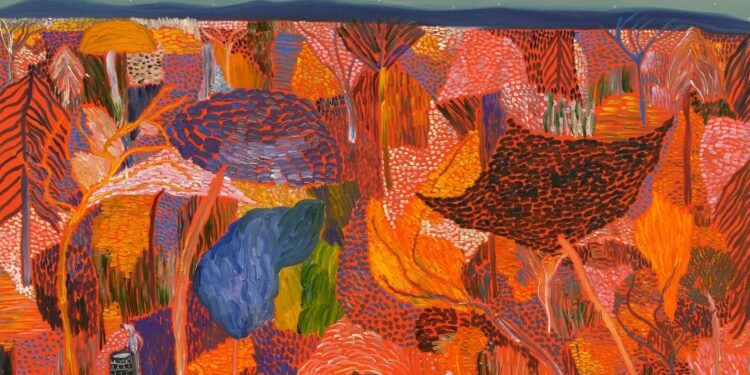

Matthew Wong‘s The Realm of Appearances (2018) highlights his trademark use of brushstrokes as well as his grasp of depth and perspective

© Matthew Wong Foundation c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2023

Wong was born in Toronto in 1984, and moved between Canada and Hong Kong throughout his youth. His earliest artistic explorations were in photography, and he gained an MA in the art form from the City University of Hong Kong in 2012. He became frustrated by what he described as the “unnatural” nature of the medium, however, and began experimenting with ink, before turning to painting.

The Amsterdam show includes more than 60 works that he made over his prolific eight-year career, ranging from early abstractions in ink to the expressive painted landscapes for which he is best known. They will be shown beside a small group of Van Gogh works including Wheatfield (1888), The Bedroom (1888), and Garden of the Asylum (1889).

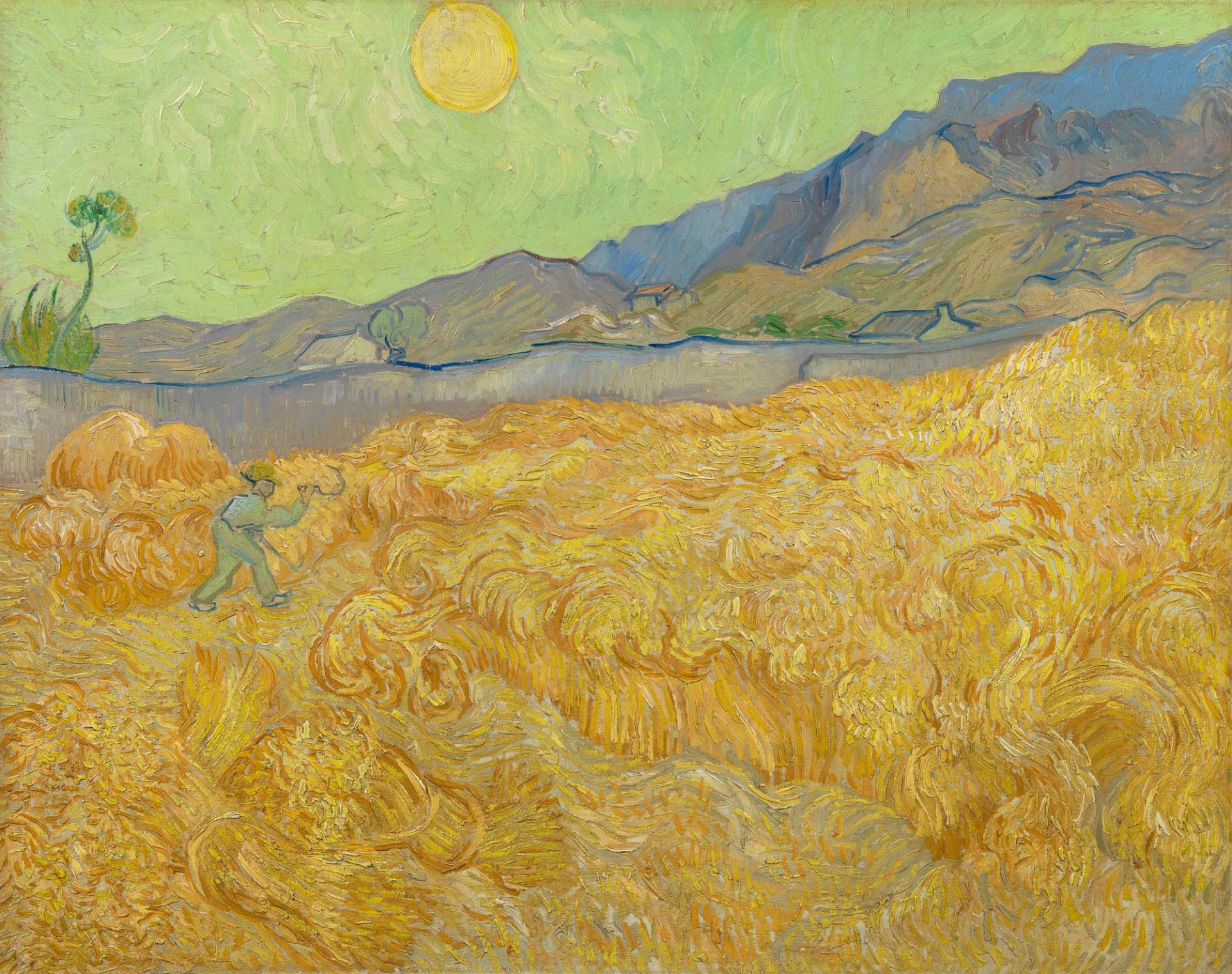

Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Reaper (1889)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Like Van Gogh, Wong struggled with his mental health, battling both Tourette’s syndrome and depression—he was also autistic. This has fed into a mythologising of Wong as a “tortured”, outsider artist, akin to Van Gogh—a factor that has fed into market demand for his work reaching particularly dizzying levels since his death. Van der Hoeven points out that the recent travelling retrospective held at the Dallas Museum of Art and MFA Boston “lowered the temperature” on Wong’s reputation by focusing on the art and artistic influences first and foremost. He explains that he seeks to do the same here, with the artist’s first retrospective in Europe.

In preparation for his show, Van der Hoeven spoke to many of Wong’s friends, who gave insight into the artistic connection Wong felt he had with Van Gogh. “Nearly all of them said that Matthew mentioned Van Gogh as an important source of inspiration”, Van der Hoeven says. The curator also had lengthy conversation with Monita, Matthew’s mother, who runs the Matthew Wong Foundation and has been closely involved in putting together the exhibition; she also said he spoke often of the Dutchman.

There is evidence beyond the anecdotes, too. For example, Wong regularly shared his work on social media—where he had a strong following—and in 2015 published a (now deleted) post showing one of his own works beside a Van Gogh. He also commissioned a catalogue essay in which his use of brushstrokes was compared to that of Van Gogh’s and the French painter Chaïm Soutine’s.

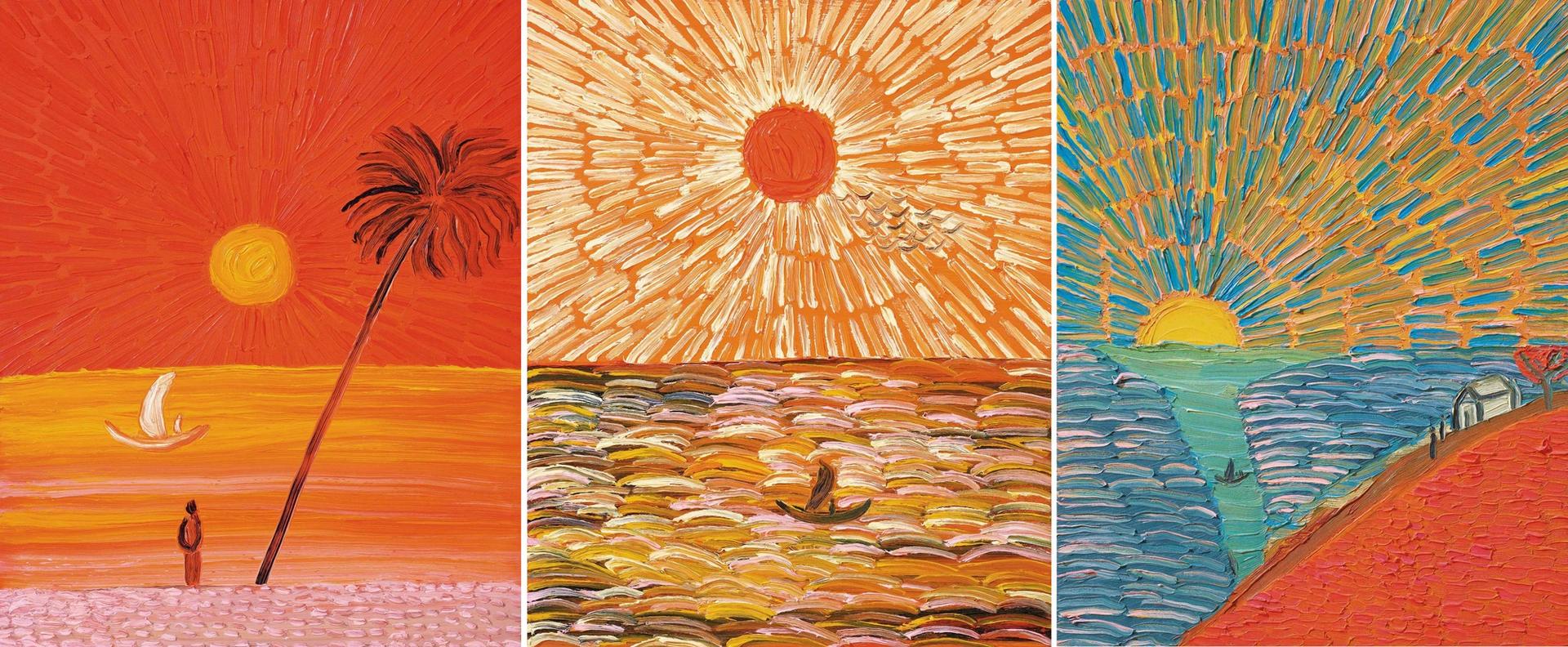

Wong’s affinity with Van Gogh will come through in a variety of ways in Amsterdam. There is a triptych by Wong titled The Journey Home (2017), in which solitary boats are shown sailing before a radiant sun at various times of the day. “That sun is very reminiscent of Van Gogh; you can almost feel the heat radiating off the painting,” Van der Hoeven says. Similarly, Wong’s Coming of Age Landscape (2018), with its dominant foreground and lush palette of blues, greens and yellows, bears striking similarities to Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with a Reaper (1889), and “demonstrates how important Van Gogh was to him in a more stylistic way”.

Matthew Wong‘s The Journey Home (2017) is reminscent of Van Gogh works in both its palette and rendering of the sun

© Matthew Wong Foundation c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2023

Other comparisons are much more on the nose. Included in the galleries will be Wong’s own iteration of Starry Night (2019), Van Gogh’s curling licks of paint replaced by short, pointillist lines and dots. In The Space Between Trees (2019), meanwhile, Wong recreates Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888), a lost work in which the artist depicted himself wandering down a path with an easel and other painting equipment in hand. In Wong’s version, he inserts a bench in place of the artist—a potent symbol, given he spent a lot of time towards the end of his life sitting on a park bench in Edmonton, Canada. For Van der Hoeven, it is both a tribute to his predecessor and a poignant approach to a self portrait—one that also recalls Van Gogh’s Chair (1888), in which the seat is itself a stand-in for the artist.

Matthew Wong created his own iteration of Van Gogh‘s 1889 painting Starry Night

© Matthew Wong Foundation c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2023

There are emotional, sensitive aspects of the show that Van der Hoeven does not wish to shy away from. One quote from Wong on a wall states about Van Gogh: “I see myself in him. The impossibility of belonging in this world.” The final section of the show, meanwhile, is about how the two artists used their art to reference their personal lives. Practical measures have been put in place to raise awareness and offer support for the public: the details of crisis helplines will be readily available, and there will be events such as mindful viewing sessions and Friday lates focused on mental health.

Through the overall narrative, however, Van Der Hoeven hopes to make it clear that these were artists who—despite having many shared interests, sensibilities and aesthetics—were very distinct. There will be an entire section showing how Wong painted, unlike Van Gogh, from his imagination, while Van Der Hoeven also points to Wong’s drive to share as much as possible and better his skills as a clear contrast to Van Gogh’s less confident approach. The show will also, crucially, highlight the inspiration Wong drew from other artists from across history including Chinese painter Shitao—most prominent in the 17th century—and the 20th-century abstractionists Joan Mitchell and Willem de Kooning.

Matthew Wong’s See You on the Other Side (2019)

© 2023 Matthew Wong Foundation / c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2023

Matthew Wong | Vincent van Gogh is the latest in a string of exhibitions that have sought to highlight Van Gogh’s influence on contemporary artists—with shows on David Hockney in 2019 and Etel Adnan in 2022 among the other examples. Van der Hoeven hopes this latest—and perhaps boldest—attempt will present the museum as “a place where you can also go to see good shows of contemporary painting”, as well as new perspectives on its resident artist.

Above all, the show is “a celebration of their art and the triumph of painting,” the curator adds. “I hope it will demonstrate that this guy from Hong Kong and Edmonton can pick up sources of inspiration like Matisse and Van Gogh, engage in a dialogue and insert himself within their ranks.”

- Matthew Wong | Vincent Van Gogh, Van Gogh Museum, Amsteram, 1 March-1 September

- In the Netherlands, support and assistance can be found by calling 113 or visiting the website of the 113 Suicide Prevention Foundation. In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. You can also text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis text line counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.