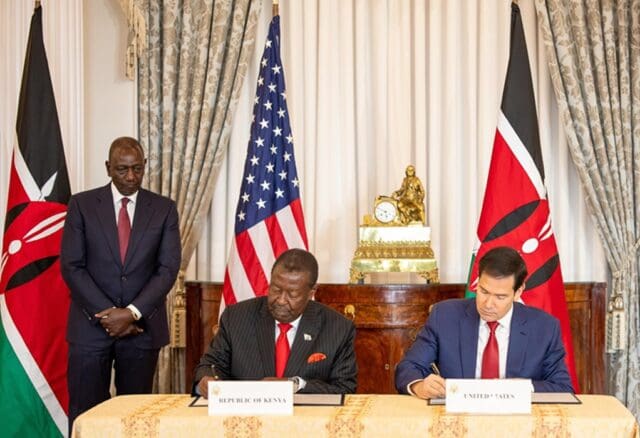

Washington / Nairobi – The United States and Kenya have formalized a landmark five-year, $2.5 billion health agreement. This deal is the first signed under the America First Global Health Strategy. With the U.S. contributing $1.7 billion and Kenya committing $850 million, the deal ushers in a new model of bilateral health cooperation.

The shift moves away from funding external NGOs. It focuses on directly strengthening Kenya’s national health system. Targets include combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. It also includes supporting family-planning programs under U.S. policy constraints, and bolstering infrastructure across public, private, and faith-based providers.

What Changes: From NGO Aid to Government-Led Health Systems

Under the new agreement, funding will now flow directly into Kenya’s national health system. This is a marked departure from previous U.S. health assistance models predominantly managed by non-governmental organizations.

This reallocation is part of a broader U.S. foreign-aid overhaul following the dismantling of USAID earlier in 2025. This decision had triggered deep concern across the global-health community for the sudden defunding of multiple programs.

– Advertisement –

Proponents argue the “America First” model emphasizes accountability, efficiency, and long-term capacity building. This is achieved by partnering directly with national health authorities rather than intermediaries.

Key Terms of the Agreement

- Funding split: $1.7 billion from the U.S., $850 million co-financed by Kenya.

- Program scope: HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, other infectious diseases, and family planning (within U.S. restrictions on abortion services).

- Providers eligible: All clinics and hospitals enrolled in Kenya’s health insurance system — including private and faith-based facilities — will receive equal treatment for government reimbursement.

- Data and specimen sharing: The agreement requires participating countries (beginning with Kenya) to share pathogen-related data — including biological specimens and genetic sequences — with U.S. authorities within days of detection.

Why This Is Seen as a Game-Changer

Toward Greater Sustainability and Self-Reliance

By redirecting funds into Kenya’s own health infrastructure and budget, the agreement aims to build sustainable capacity — reducing dependence on foreign-run NGOs and external funding cycles.

Under the previous funding freeze earlier in 2025, many essential services in Kenya — including HIV prevention, maternal care, immunization, and data-reporting systems — faced serious disruptions.

Streamlined Aid, Fewer Intermediaries

Supporters of the new model say it reduces inefficiency, cuts overhead, and ensures that funds reach where they’re most needed. This includes clinics, hospitals, and health workers on the front lines.

Strategic & Political Dimension

Health aid under “America First” appears tied to foreign policy aims. Beneficiaries are likely to be U.S. allies. The choice of Kenya is symbolically significant. U.S. officials said similar deals with other partner countries are expected in the coming weeks.

Challenges & Criticisms

Critics caution that the shift away from NGO-led programs could undermine flexibility. This is especially true for community-level interventions, outreach among marginalized groups, and rapid response to crises. A major concern is whether national systems alone can maintain coverage and quality across rural and underserved areas.

Also controversial is the data-sharing requirement. While early detection of pathogens is a public-health priority, some global-health proponents warn it could erode sovereignty over biological data. It may also raise equity issues around access to any resulting vaccines or treatments.

Finally, the dismantling of USAID earlier this year left a gap. Many argue that the scale and scope of prior NGO-led programs — including maternal care, immunization, nutrition, and HIV prevention — simply cannot be replicated by centralized government systems alone.

What Comes Next

U.S. officials have indicated that similar bilateral health deals — modeled on this Kenya agreement — are likely to be rolled out within weeks. These will target other countries identified as strategic partners.

For Kenya, this deal marks the beginning of what proponents hope will be a stronger, more resilient push toward universal health coverage. The agreement aims for better disease surveillance and long-term health-system strengthening. Health leaders in Nairobi have hailed the pact as a major milestone.

At the same time, global-health advocates and civil-society groups will be watching closely — assessing whether the new system delivers on promises of sustainability without sacrificing access, quality, or inclusivity.