The leading British artist Joe Tilson has died aged 95. His death was confirmed in an online statement issued by Cristea Roberts Gallery, who co-represent the artist. The gallery said in a statement that Tilson was “one of the founding figures of British Pop [and] an enthusiastic proponent of political activism, sexual liberation and social change”.

Earlier this year Tilson underwent a renaissance, showing work in two London shows—at Marlborough and Cristea Roberts Gallery—and was the subject of a new monograph by Marco Livingstone, published by Lund Humphries. In an Instagram post, Livingstone said: “Tilson successfully avoided both the pitfalls of staying still—not wishing to create a brand—and of randomly changing direction, having no inclination to chase every new fad in a desperate bid to maintain visibility.”

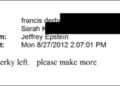

Joe Tilson’s Proscinemi for Dionysos (1982)

Courtesy the estate of Joe Tilson and Cristea Roberts Gallery, London © estate of Joe Tilson

Tilson, who was born in 1928, grew up in south London and worked as a carpenter before serving in the Royal Air Force between 1946 and 1949. He later studied at St Martin’s School of Art, London, in the early 1950s where he met Peter Blake, Allen Jones, Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, part of a group of emerging young British artists.

In an interview with The Art Newspaper earlier this year, Tilson said: “I arrived at St Martin’s and who also arrived? Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. It’s like saying I was in Holland and I met this bloke called Rembrandt.” Some of his most celebrated Pop Art compositions include Secret (1963) and the A-Z Box of Friends and Family (1963), a quirky homage to colleagues and loved ones.

Joe Tilson’s The Stones of Venice, Depositi di Pane (2018)

Courtesy the estate of Joe Tilson and Cristea Roberts Gallery, London © estate of Joe Tilson

In the 1960s Tilson moved to rural Wiltshire, veering away from Pop art and focusing on other subjects such as Greek mythology and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Australia. The artist also spent much of his life in Italy, where he had homes in the Tuscan hills and in Venice.

He was elected a Royal Academician in 1991; in 2002 the Royal Academy held a major retrospective, Joe Tilson: Pop to Present, celebrating his decades of printmaking.

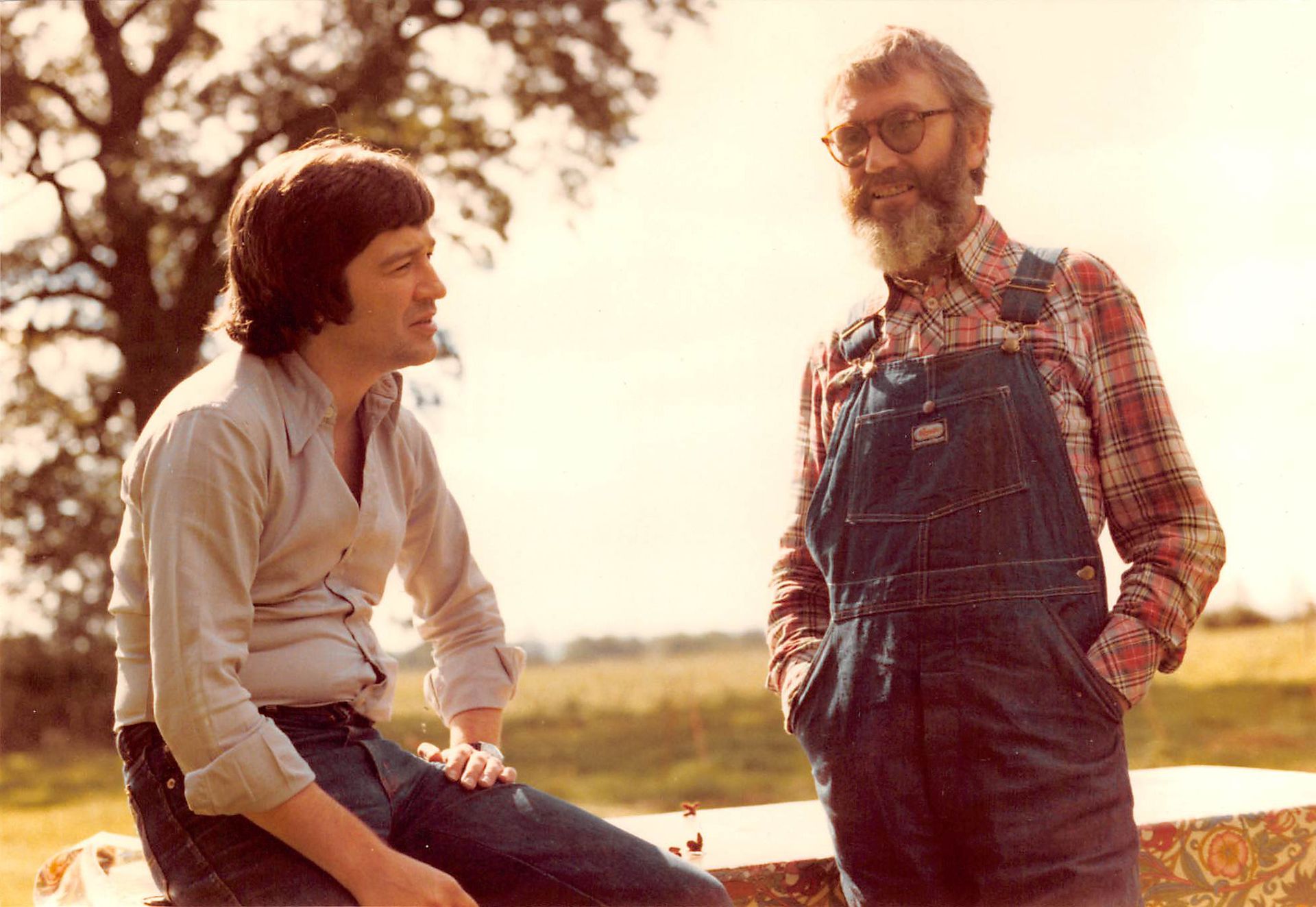

Alan Cristea and Joe Tilson in Christian Malford, Wiltshire, 1970s © Alan Cristea

The dealer Alan Cristea also paid tribute, saying: “When I started my own gallery in 1995, he was the one constant reference point. We continued to publish his editions together, still as technically inventive and gloriously colourful and exuberant. His love of printmaking never ebbed and his generosity never waned. He was one of the most inventive printmakers with whom I ever had the privilege to work.”

This spring, Tilson told The Art Newspaper: “The best thing is to go to the gallery. What artists say about their work, I wouldn’t take any notice of that. A lot of people think: ‘There’s the meaning.’ No, no. The meaning’s in you. People don’t apply themselves to art. They take it superficially. But art is a lot of hard work. It takes training, it takes travel. People have got to work at it. To understand art is very, very difficult.”

Of posterity, he said: “No, no interest whatsoever. There’s nothing you can do about the meaning of your work. Life’s life. I just take it the way it comes. So much depends on chance.”