Western governments are seeking to build more mines and refineries for critical minerals, given their necessity in not only clean energy technologies like electric vehicle batteries but also defense applications like hypersonic glide vehicles. Australia, Canada, and the United States have been particularly active in funding domestic mineral projects, and the European Union is set to begin vetting mineral projects soon. But beyond capital challenges (and local opposition), the West’s paucity of mines and refineries faces structural realities: geology and technology.

To address these challenges, Western governments should continue offering funding such as grants for drill programs and loans for processing facilities, but they should prioritize mineral extraction and processing capacity that supply their defense industries.

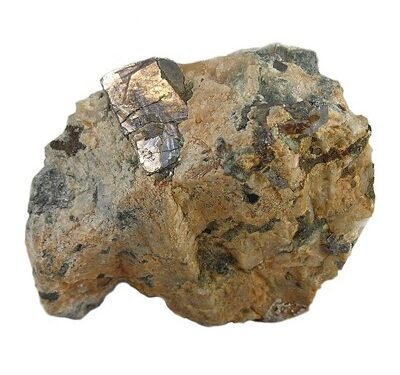

To build more mines, companies need profitable deposits. The profitability of a mine depends on numerous factors, including the targeted element’s price, ore type, mine depth, surrounding infrastructure, and, arguably most importantly, deposit scale and grade. In the West, most large-scale, high-grade deposits have been discovered, are being mined, or have been fully mined. For example, the most recent major nickel sulfide discovery occurred in 1993 at Voisey’s Bay in Canada.

Consequently, smaller-scale and lower-grade mines would likely be marginal producers with higher capital intensity and operating costs, meaning they would struggle to remain profitable and operational amid lower mineral prices. For example, Molycorp, the former owner of the Mountain Pass rare-earths mine in California, declared bankruptcy in 2015 when rare earth prices fell; last year, Jervois suspended final construction at its Idaho Cobalt Operations mine amid low cobalt prices. More recently, First Quantum Minerals placed its Ravensthorpe nickel mine in Western Australia on care-and-maintenance status due to low nickel prices, and BHP is considering the same for its own nickel assets there.

To build more refineries, companies in the West need the requisite technology and know-how. Yet these companies tend to lack expertise in building and operating mineral refineries—as those skills were largely ceded to China decades ago. For example, the United States has no large-scale commercial refineries of nickel or cobalt, although Australia and Canada do. Still, building and operating new refineries in Western countries will likely take longer and cost more than expected. For instance, with the refining technology of high-pressure acid leaching, Western-run plants often bust their budgets, fail to open on time, miss production goals, and remain insufficiently profitable.

New refineries in Western countries may even have to rely on Chinese technology. In 2022, for example, Chinese companies had ownership stakes in six of the seven high-pressure acid leaching plants operating and under construction in Indonesia. Chinese companies regularly build these plants on time and under budget. But if Western companies do decide to rely on Chinese processing technology, China can cut off access to this processing technology, just like its ban last year on exports of rare earth processing technology.

Despite these geological and technical challenges, Western companies are making advances in mineral extraction and processing—often with government support, such as grants for exploration, loans for processing, and research funding for novel extraction and refining methods. For example, the U.S. company MP Materials received $45 million in grants to build America’s only integrated rare earth mine and oxide production facility. The money came from the Pentagon, arguably the most active government department in funding mineral projects.

While Western countries currently lack sufficient economically viable mineral reserves to satisfy their total mineral demand, they could aim to increase mineral extraction and processing capacity to volumes that meet a good portion of their defense industries’ mineral demand, which is often less than other sectors. For example, in the United States, 17 percent of beryllium products were used in aerospace and defense applications in 2023.

Moving forward, Western governments should continue to fund mines and refineries in their jurisdictions, helping them to overcome geological and technical challenges. But they should prioritize funding for mineral extraction and processing projects that supply defense industries given the necessity of secure mineral supply chains for national security.

Gregory Wischer is a non-resident fellow at the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines.

Morgan Bazilian is the director of the Payne Institute for Public Policy and a professor of public policy at the Colorado School of Mines.