Katie Ludlow Rich and Heather Sundahl had prizes to give away. “Which founding mother from Exponent II was banned from speaking at Brigham Young University?” Rich quizzed a small, mostly female audience gathered inside a conference room at the University of Utah.

Hands flew up.

“Laurel Thatcher Ulrich!” one woman shouted, naming the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who famously observed that “well-behaved women seldom make history.”

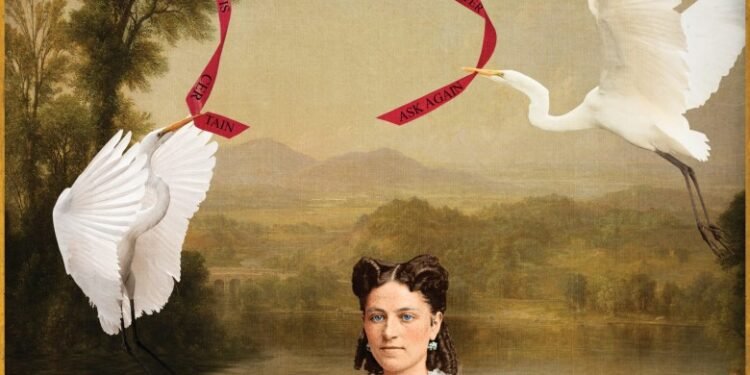

“Yes,” Rich smiled, awarding her a tall prayer candle emblazoned with an illustration of a Mormon feminist. “1993. The shadowy ban,” she said, pointing to an important moment in Ulrich’s history.

Rich and Sundahl were speaking about the 50-year history of Exponent II, a Mormon feminist magazine, at the annual Sunstone Symposium, a conference dedicated to progressive Mormon scholarship. (Full disclosure: The author received an honorarium for giving the keynote lecture at the conference.) In this room, everyone seemed familiar with the magazine, rattling off the names of former editors as if they were rock stars.

Over the past five decades, Exponent II has carved out a community where people can explore the ways in which Mormonism and feminism collide, and the friction created by those dueling identities. Throughout that time, the Mormon Church has repeatedly ostracized its feminist members, including some who have written for Exponent II.

Recently, Rich and Sundahl, longtime contributors to the magazine and its blog, published a comprehensive history of the publication, Fifty Years of Exponent II, which features an afterword by Ulrich. They lay out the breadth of perspectives offered by the magazine over the decades as its writers grapple with what it means to be both a Mormon and a feminist: “Dual identities,” they write, are also “dueling identities.”

The magazine offers a more accurate portrait of Mormon life than is commonly portrayed in popular media, according to Rachel Rueckert, the magazine’s editor, and it represents a culture that is much more complicated and interesting than people outside the faith realize. “My friends are everywhere on the Mormon spectrum,” she says. “I know a lot of Mormon atheists. I know a lot of queer Mormon folk. Where are their stories represented?”

THE MAGAZINE WAS FOUNDED in Boston by women who belonged to the LDS Church at the height of the women’s liberation movement. The first issue was published in 1974. The new quarterly took inspiration for its name from The Woman’s Exponent, a suffragist newspaper created by Mormon women in the late 1800s.

The intent was for Exponent II to feature recipes, homemaking advice and women’s views, all delivered in a style that read, as its first editor put it, like “a long letter from a dear friend.” It would be mailed to Mormon meeting houses nationwide. The magazine gave women a voice, though still a very conservative one: “Their brand of feminism,” Rich and Sundahl write, “was consistent with the church’s aims.”

Exponent II’s first editors were optimistic that the wider church would embrace it “with open arms,” Sundahl said. The first issue was pointed: inside were discussions of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and women’s education alongside recipes for cranberry mousse and wheat bread.

The church leadership was nonetheless displeased and reacted as if a good Mormon wife had burned her bra in front of the church’s then-president and prophet, Spencer Kimball himself. The problem was, in part, that Exponent II’s first editor was married to a man who held a position of power in Boston’s LDS community. Church authorities flew from Salt Lake City to Boston to caution the magazine’s staff against future publishing plans. One said it “smacked of an underground newspaper” and warned the editor that people might think it was a church-sanctioned publication, given the editor’s husband’s position. In 1975, she stepped down. But the publication kept going.

Exponent II has carved out a community where people can explore the ways in which Mormonism and feminism collide, and the friction created by those dueling identities.

Given the church’s strong views on gender, the reaction was not surprising. The highest seats of power and the priesthood are reserved for men. The word “patriarchy” is used frequently in the faith: Counsel and guidance bestowed by priesthood holders are literally called patriarchal blessings. “In Mormonism, there’s quite a lot of attention to gender roles,” said Caroline Kline, assistant director of Global Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University and a co-founder of Exponent II’s blog. “If you’re a liberal feminist, as am I, you’re probably going to struggle with the fact that women do not have the priesthood and therefore are not included in the ecclesiastical structure in the same way men are.”

Additionally, the church has, throughout its history, suggested that women should prioritize motherhood over other pursuits. “Beguiling voices in the world,” wrote LDS President Ezra Taft Benson in 1981, “maintain that some women are better suited for careers than for marriage and motherhood. These individuals spread their discontent by the propaganda that there are more exciting and self-fulfilling roles for women than homemaking.”

One modern church manual is slightly less explicit: Women “have, by divine nature, the greater gift and responsibility for home and children and nurturing there and in other settings.”

As Exponent II became a leader in Mormon feminist thought, it posed an existential threat to a church where men are viewed as the heads of the household and holders of the priesthood. “What Exponent does is it teaches women to listen to their internal authority,” Sundahl told High Country News. “It teaches women that you have the power in you.”

And that is radical.

THROUGHOUT THE MAGAZINE’S lifespan, the LDS church has shown increasing hostility toward Mormon feminism. In 1979, academic Sonia Johnson — who once called the LDS Church “the last unmitigated Western patriarchy” — was excommunicated after founding a feminist group called Mormons for ERA.

In 1993, the board of Brigham Young University rejected a recommendation that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich — the faith’s only female Pulitzer Prize-winner and one of the founders of Exponent II — speak at BYU’s annual Women’s Conference. It offered no explanation for its decision. That same year, three feminist thinkers — part of a group of Mormon academics branded the “September Six” — were excommunicated. More recently, in 2014, the church excommunicated Kate Kelly, the Mormon feminist who founded Ordain Women, an organization calling for women to gain the priesthood. (HCN requested comment from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints about Exponent II and its stance on feminism but did not receive a response.)

Despite these clashes, Exponent II continues to unflinchingly dive headlong into hot-button topics including abortion access, marriage equality, sexual abuse and the priesthood. The magazine comes out quarterly in print, and the blog publishes new essays several times per week. In a 2007 post titled “Radical Mormon Feminist Manifesto,” Jana Remy, the blog’s co-founder, pushed back on the idea that the church could define people’s identity or decide whether they had a place in the faith. “We will no longer passively submit to secondary status,” she wrote. “We reject church teachings about the eternal nature of traditional gender roles and will not sustain official proclamations from the church leaders that reify such notions of women and men conforming to specific narrow roles such as submissive wives, full-time mothers, bread-winning fathers.”

“It teaches women to listen to their internal authority. It teaches women that you have the power in you.”

The manifesto advocated for equal partnerships, co-parenting, support for single parents, for women and people of color to be leaders of the faith, and for the inclusion of LGBTQ members in temple ordinances. “We affirm that as the LDS Church moves into the 21st century,” Remy wrote, “it can no longer ignore and reproduce the multiple oppressions of sexism, racism, and ableism that are endemic to its patriarchy hierarchy.”

Kline called Remy’s piece “prophetic.”

“She laid out where Mormonism should go in terms of issues of equality and gender and race,” Kline said. “This is exactly where Mormon feminism went. She was just a decade or two in front of everyone else.”

As the years passed, the magazine became a place for the wider community to gather and process the increasingly restrictive policies handed down by the church. For example, in 2015, the church prohibited the children of same-sex couples from receiving church blessings, including baptism, until they turned 18 and decried same-sex unions.

In response, Exponent II “chose a side,” wrote Pandora Brewer in the magazine’s Spring 2016 issue, which was devoted to perspectives from those most affected by the policy. “We believe that this is a troubling, divisive policy.” (The church revised it in 2019.) And in August 2024, when the church banned trans people from being baptized and working with children, and required them to be supervised in restrooms at events, people again turned to Exponent II to process it. “The indignation at the cruelty of these policy changes towards transgender people burns within my bosom like the raging fire prepared to receive the hewn trees with rotten fruit spoken of in the scriptures,” one blogger wrote.

Rich said the magazine’s readers don’t see Mormon feminism as just one thing; within the community, there is plenty of struggle and debate about what that identity looks like. The point, she said, is that people get to define it for themselves.

Rich is no longer an active member of the church; the 2015 policies were one reason she pulled away. Exponent II helped in her faith transition. “To hear or to encounter writings by these really smart women who were processing and talking about these things that I also found upsetting was both validating and scary,” she said.

Sundahl remains an active member of the faith, though her four adult children have all left the church. She said that being part of Exponent II has been a refuge — proof that it’s possible to stay in the church and be a feminist.

In 2008, Sundahl authored a piece for the blog called “Baby Killer,” telling the story of a miscarriage she experienced at 17 weeks. Her doctor sent her to a Utah abortion clinic for a late-term dilation and evacuation procedure that is done to remove remaining fetal tissue.

“As this Mormon mother of three, I went to an abortion clinic,” she said. “You have these ideas of who you are, and you’re like, good Mormon girls don’t go to abortion clinics.”

“To hear or to encounter writings by these really smart women who were processing and talking about these things that I also found upsetting was both validating and scary.”

Sundahl wrote of the horror she felt walking past a protester to get into the clinic. “An older man, perhaps in his sixties, stood in front of me with a sign. He looked like a temple worker on his day off. On the poster was a picture of a dead fetus and the words ‘Baby Killer,’” she wrote. “Part of me longed to explain to this man that I wasn’t a baby killer like the other women in there. I was a Mormon, a baby maker.”

“I felt obligated to talk about it,” she said later, reflecting on the piece in an interview. “I need to put out there that we have these binaries: abortion clinic, good Mormon mommy. Those two things don’t go together. And I’m like, ‘OK, but that’s me. I’m both those things.’

Her piece received many comments from Mormon women describing their own miscarriages and the pregnancies they were currently struggling with. “People underestimate how complicated all of these issues are,” one commenter wrote.

But being so up-front comes at a cost, too. When people drop their subscriptions, Rueckert’s staff solicits feedback on why they left.

“It’s usually one of two things,” she said. “It’s like, ‘You’ve gotten too spicy, you’re too far left.’ Or the opposite: ‘You guys don’t take a hard-enough stance, it’s not progressive enough.’”

She laughed.

“Honestly, as long as we keep getting responses on both sides, I’m doing my job.”

Note: This story was updated to clarify a quote from Caroline Kline, in which the word “can” was changed to “are.”

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This article appeared in the December 2024 print edition of the magazine with the headline “The passion of the Mormon feminist.”