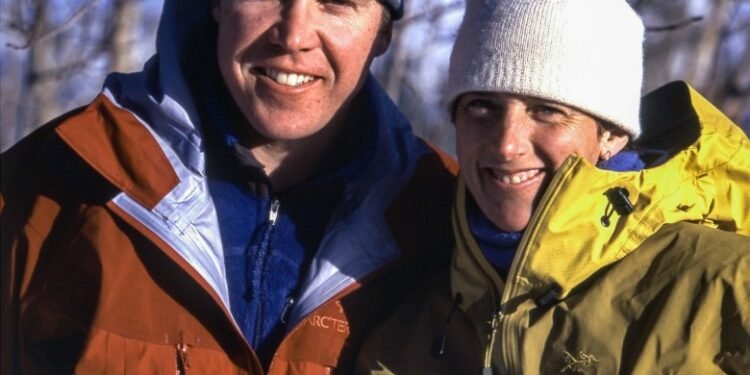

In the spring of 2003, newlyweds Karsten Heuer and Leanne Allison strapped into cumbersome packs and skinny skis and set off across the snow near Old Crow, in Canada’s Yukon. Heuer, a wildlife biologist, and Allison, a filmmaker, intended to follow members of the Porcupine caribou herd on their long migration to calving grounds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, across the border in Alaska. Through trial and error, with patience and diligent attention, the couple managed to fall into step with pregnant cows rushing northwest through rugged terrain and howling storms, desperate to reach the coastal plain’s nitrogen-rich plants before they gave birth.

The journey was hungry and hard, spanning more than a thousand miles. Fat fell away from Heuer’s and Allison’s limbs, just as it did from caribou bodies. The pair began to hear a sort of hum when caribou were close, began to dream caribou through the night, began to feel the land they traversed as a heartbeat and extension of their own bodies. “Ours was just one thread of one migration … one chapter in a multitude of stories,” Heuer later wrote of watching smaller groups of caribou converge over hills and valleys into a great flowing, grunting, thrumming throng. Alongside them flitted Lapland longspurs and horned larks; above them flapped Vs of geese and swans. All were bound for the brief summer bounty of the Arctic, pressing onward over countless generations and thousands of years, despite prowling wolves and bears, despite lethally abundant blood-sucking insects — determined to get there or die in the attempt.

Even when Heuer and Allison lost track of their animal companions, they didn’t travel alone. They carried an action figure of then-President George W. Bush to show him the living, breathing, connected world that he would fracture if he and Congress opened the coastal plain to oil development.

And, in a way, Heuer and Allison carried me, too.

In 2007, I was 25 years old, working my first non-seasonal job as a newspaper reporter in the ski-resort town of Aspen, just a few hours from where I grew up on Colorado’s urban Front Range. I loved being outside, backpacking in the surrounding mountains, getting closer to cushion plants and lichen and pikas and sky. But the outdoor media I encountered during that time felt like it was about something else, celebrating an idea of human achievement in which the wild was either scenic backdrop or challenge — a substrate for discovering how far intrepid individuals could push themselves. I saw little of what I loved in this world of “first” ascents and descents, where people climbed a mountain “because it’s there.”

Then, I picked up a copy of Being Caribou, the book that Heuer had written about his and Allison’s journey in hopes of getting more people to care about and fight for the well-being of the Porcupine herd. The book led me to Allison’s film of the same name. As skiers whizzed down Aspen Mountain beyond my apartment window, I followed Heuer and Allison through the Richardson Mountains and across the churning Firth River. But more importantly, I followed and felt caribou I had never seen and tundra, plains and peaks I had never crossed. The book and the film used the limits of human bodies to cultivate empathy for the experience of other beings: how much stronger they were, the hardships they faced in their quest to thrive and bring more of themselves onto the Earth, the ways industrial infrastructure would harm them.

The book and the film used the limits of human bodies to cultivate empathy for the experience of other beings.

Many other people took the same journey I did. Heuer and Allison’s works were part of a broader, older movement of culture-making about the importance of the coastal plain, said Finis Dunaway, a historian at Trent University and author of Defending the Arctic Refuge: A Photographer, an Indigenous Nation, and a Fight for Environmental Justice. For decades, the Gwich’in on both sides of the Alaska-Yukon border have fought to keep drilling out of the calving grounds that are so crucial to the caribou that they live alongside and hunt and hold sacred. Photographers, writers, filmmakers and others have rallied to the cause as well, sometimes alongside Indigenous leaders. Allison’s film spread through watch parties and events; Heuer’s book passed from shelves to hands to other hands. The couple sat on panels with other makers, did speaking engagements, inspired people to write letters, stand at rallies, learn more. It can be easy for historians to overlook these kinds of efforts, Dunaway told me: They “seem so far from the center of action on Capitol Hill, and they seem very small-scale and grassroots. But they exerted a huge impact, a surprising impact, on galvanizing public concern and getting people engaged.”

Those impacts weren’t just political. For me, Heuer’s book was deeply personal. I saw exciting storytelling possibilities in its inversion of the adventure narrative form that I found so alienating. The caribou herd’s journey gave me new ways to understand the wild landscapes of my home region, divided by invisible state borders and busy highways that challenge migrating pronghorn and mule deer. And it helped seed the love of Northern landscapes that would shape parts of my own career.

Karsten Heuer died in November at just 56 years old, after being diagnosed with a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. When I read the news, I sagged with loss, grieving all he had given me, and all he had yet to give. Then, I picked up Being Caribou and read it again. With a new federal administration dead set on oil development in Alaska, its reminder that “we need to work from the bottom up” to protect the coastal plain is as relevant as ever.

The book ultimately sold about 7,500 copies in the U.S. It wasn’t the sort that breaks sales records or draws massive crowds to readings, said Helen Cherullo, who shepherded the manuscript at Mountaineers Books. But it had a way of touching the right people, changing how they lived their lives and saw the world — motivating them to share those changes with others. “It’s not really the number of people that show up,” she told me. “It’s who shows up.”