How could something that may seem as benign as funding preschool for grandchildren spark tension in a close family?

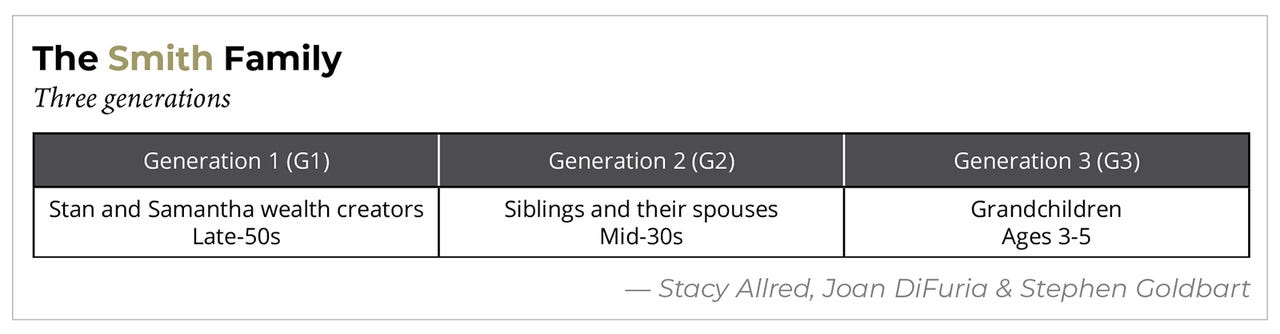

Let’s imagine a hypothetical1 three-generation family. Stan and Samantha (G1), the wealth creators of the Smith family,2 strongly value education. They have adult children (G2) who now have their own children (G3). Stan and Samantha were excited to fund their grandchildren’s education, starting with preschool for their three oldest grandchildren, born 18 months apart. See “The Smith Family,” this page.

This seemingly simple and generous gift raised concerns and tensions among G2. Stan and Samantha felt that if they didn’t address these concerns swiftly, they would fester and worsen.

We were asked to facilitate a family dialogue. We began by asking each participant to share their understanding of how G1’s preschool funding works. What ensued could have been a comedy skit on Saturday Night Live! It was clear that family members had different assumptions about the “rules” and different responses based on the history of their family dynamics.

G1 were both surprised and upset that such complex questions arose from what started as a straightforward intention to fund faith-based preschool tuition, honoring the tradition of the siblings’ preschool experiences.

Navigating the Tension

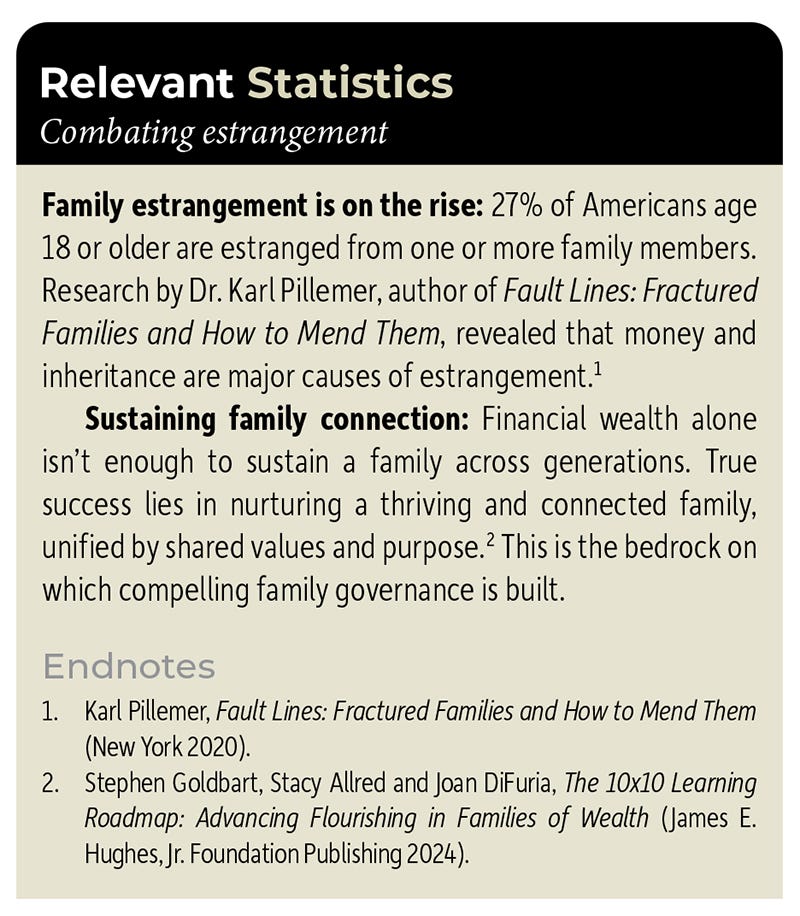

These questions and conflicts aren’t unique to the Smith family. They often arise when the grantor’s positive intentions are perceived and interpreted through the filters of family dynamics and absentee governance. To address these and related challenges, and to build conflict resilience, we recognized the need for a structured decision-making process, supported by policies and practices that “speak to the details” and are attuned to the dynamics of a family’s multigenerational culture. Our goal has been to create a family governance framework that meets this need and helps move the family toward greater clarity and alignment. See “Relevant Statistics,” p. 35.

Guiding the Journey

How do advisors guide the journey toward a thriving and connected family of wealth? Here are some considerations:

Can the Family Wealth Governance Policy System (the GPS) serve as a tool to lower family conflict? Recognizing that while estrangement results from a complex web of factors, and there’s no single magic solution, we’ve experienced the power of thoughtfully crafted, relevant governance to build conflict resilience.

We reached out to Dr. Karl Pillemer, a leading researcher in family conflict, to get his viewpoint. Dr. Pillemer strongly endorsed this approach as a tool to step back and engage in a rational process. As Dr. Pillemer shared:

It may be a cliché, but it’s true that fights about money are never just about money. What families need are clear, structured processes that everyone understands before decisions need to be made. When families have transparent frameworks in place—with explicit criteria, defined responsibilities, and agreed-upon procedures—it removes the emotional ambiguity that fuels conflict. Family members aren’t left wondering ‘why did they get more?’ or ‘what are the rules?’ The structure itself becomes a protective factor.3

Family governance often takes too long. At a recent family governance conference, our biggest takeaway was the sentiment of leading consultants that developing family governance takes much longer than families think it should! Family offices also report that governance development can take too much time and energy, leading to frustration and loss of family member participation. Given today’s speed of change and complexity, developing thoughtful, practical governance is more relevant than ever before. Families can’t afford to lose momentum. Yet, as organizational consultant Dr. Dennis T. Jaffe points out in his article, “Finish What You Started,”4 all too often, families fail to take the final steps needed to complete and implement the governance they initiate.

Developing meaningful governance requires time. But these stories of frustration motivate us to innovate and create a framework that provides structure and efficiency while enabling family members to share unique viewpoints and capture those perspectives in a tailored approach to governance.

The GPS

Governance is more than about setting rules—it’s the art and science of how we make decisions, communicate our values and craft and preserve our legacy. It’s also an iterative journey, not a destination. The GPS provides a clear methodology for designing governance policies that reflect a family’s unique identity and aspirations.

The GPS is a transformative tool designed to guide families as they craft their decision-making practices. By focusing on thoughtful family governance, the GPS can help families gain clarity and create an intentional pathway toward more cohesive group action. At its core, the GPS is a decision-making framework rooted in what matters most to each family.

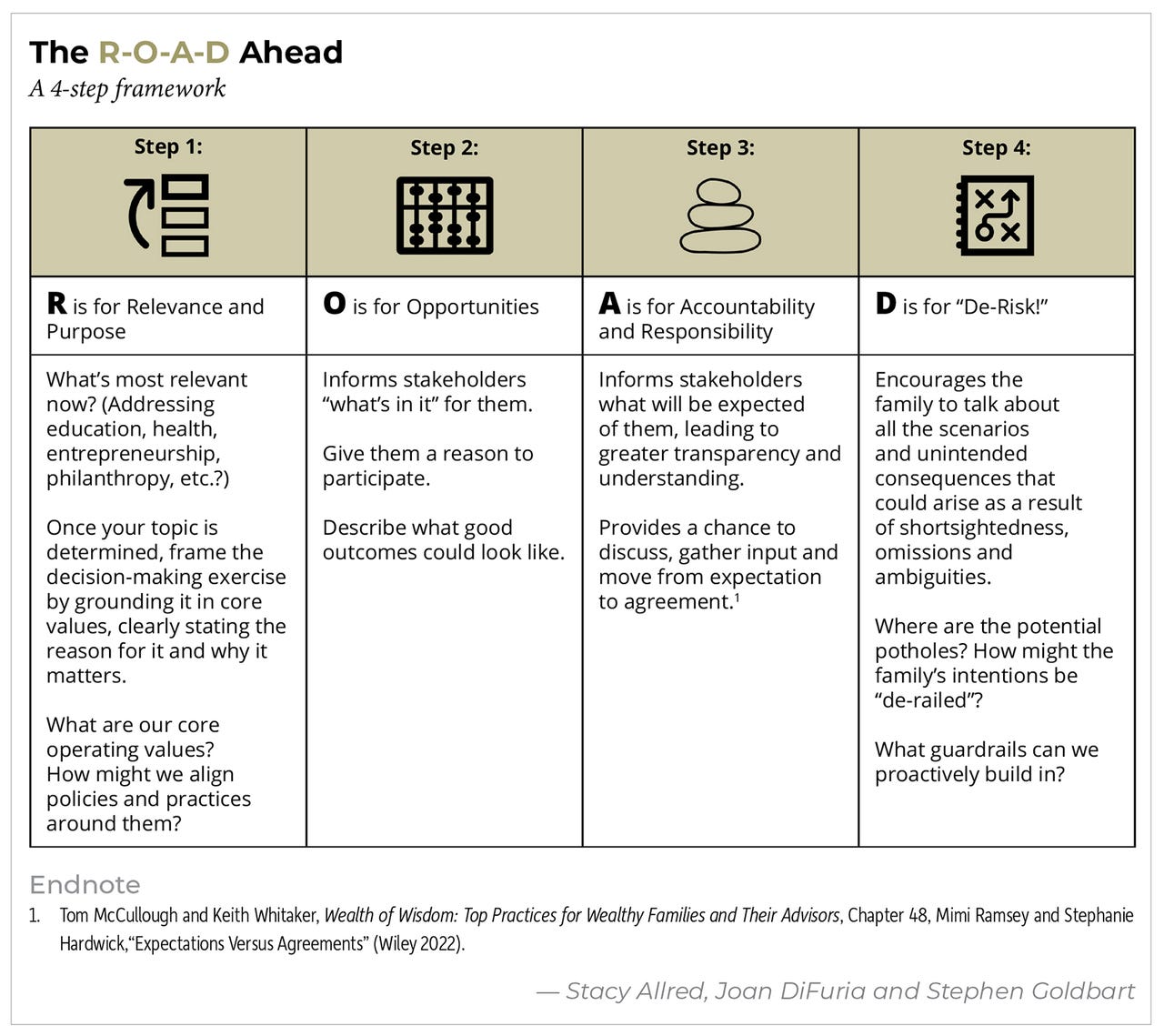

The R-O-A-D Ahead

The GPS is a 4-step framework that invites the family into a constructive, intergenerational and planful dialogue about the “what,” “why” and “how” that supports a particular policy or decision. Families are empowered to create policies that not only distribute assets but also strengthen relationships, nurture individual potential and contribute to a collective legacy. See “The R-O-A-D Ahead,” this page.

Applying the 4-step R-O-A-D framework: While families can thoughtfully build governance at any time, it’s optimal to anticipate what’s around the corner and build the policy in advance. Developing a policy about using marital agreements is easier before a fiancé enters the picture. For the Smith family, their unexpected conflicts around funding preschool became the on-ramp for applying the 4-step R-O-A-D framework. This process created an opportunity to develop an education policy that provided structure for making thoughtful, family-sensitive decisions.

Using the GPS process, the family explored and resolved key questions, including:

• Was the purpose of the gift to fund preschool education in general or more specifically to support faith-based education?

• If different schools charged different tuition rates, would all tuitions be covered regardless of amount, or would there be a funding “cap”?

• What responsibilities did G2, their spouses and G3 have in receiving and managing this educational support?

With guidance and facilitation, the family clarified the purpose of this dialogue, characterizing it as a “learning conversation” that created space for G2 to share input to help inform their parents’ ultimate decisions. The family then reframed the gift of preschool tuition by considering the “jobs to be done” through it, that is, the underlying purposes and outcomes the funding was meant to serve.

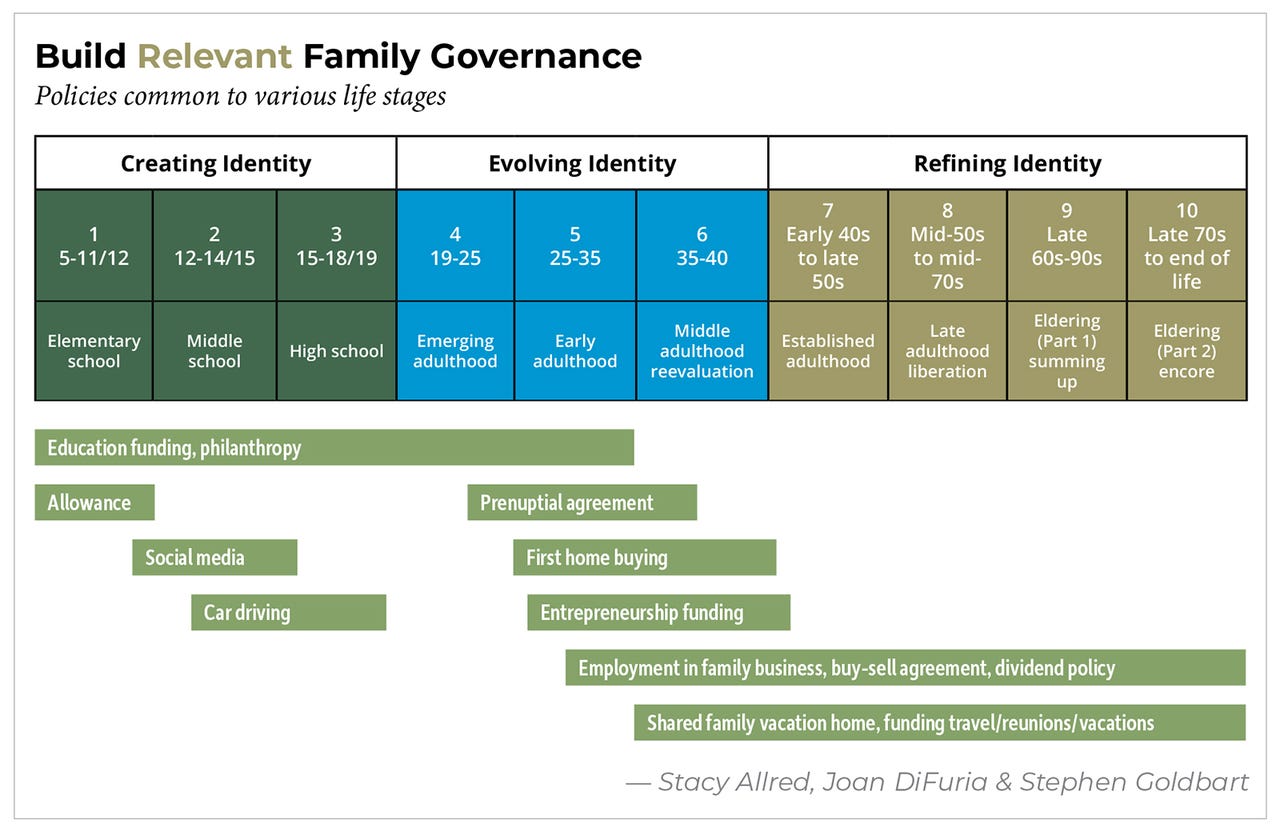

Governance and life stage: While timing is unique to each family, “Build Relevant Family Governance,” this page, overlays the 10 life stages in the 10×10 Learning Roadmap5 to policies common to various life stages.

Model in Action

To expand on the use of the GPS to guide the governance journey, let’s go into detail about two popular topics: (1) addressing family funding for first home purchases; and (2) entrepreneurship.

Developing a first-time home buying policy. Making the model come alive, let’s apply this framework to create a first-time home buying policy. This practical application will help families move from ambiguity to alignment, from reactive decisions and scattered actions to intentional, strategic choices, and from simply achieving financial success to using it wisely to support true thriving.

Here are the four steps in a sample first-time home buying policy:

Step 1: Relevance and Purpose

We value:

• Empowering family members to build roots in a vibrant, safe neighborhood with a strong sense of place and ownership through a foothold in real estate

• Fairness in our decision-making process, including transparency about first home distributions among all siblings

• Supporting thoughtful decisions through the home buying process with financial guidance and education from trusted advisors

• Leveraging financial capital to support a down payment for a first-time home

• Thoughtful planning so that family money enhances (not undermines) relationships (within the family and the couple)

• Allowing the rising generation to stay in proximity to family by combating the high cost of housing

Step 2: Opportunities

Partnering with each family member for a down payment of a first home of $500,000 (in 2025 dollars, indexed for inflation)

• Funds designated for a first home are often kept within real estate-related assets. If a home purchase isn’t imminent or if the property value is below $500,000, excess funds may be set aside for a future down payment or remodel. This distribution is independent of any inheritance in the future

Using the purchase of a first home as a learning opportunity about making sound, sustainable investments:

• Family members learn about details involved in purchasing and financing a home (understanding loan-to-value, different loan options, tax implications, ongoing maintenance costs and factors impacting value)

• Understanding the value of a dollar and making a wise purchase by understanding the market

• Understanding the benefits of a good location: safety first, good schools and climate-resilient (for example, ideally avoid flood and fire zones)

• Supporting home purchase in a way that enhances the recipient’s self-esteem and autonomy, balancing support with the rising generation and building independence with clear responsibilities of ownership

Step 3: Accountability and Responsibilities

Demonstration of “skin in the game” regarding both the financial investment and direct responsibilities of the purchase and ownership (due diligence and property management/maintenance):

• Receiver: Plan to showcase ability and budget to fund purchase price (over $500,000 family gift) and the ongoing expenses of ownership, including mortgage, real estate taxes, homeowner’s insurance and maintenance

• Receiver: Provide an analysis showing vetting of property, including neighborhood analysis, property comparables and three loan opportunities

• Giver: Transparency about what’s okay and what’s not okay to avoid confusion and future conflict

Step 4: De-Risk

Help to prevent the misuse of family gifts for a first home by ensuring home purchase within the recipient’s financial abilities to afford, own

and maintain.

Transparent and consistent communication about policies and practices to all family members:

• Deploying a fair process and making equal gifts for the down payment

• Setting clear limits about what we’re willing and not willing to do

• Being clear about our desire to support, not undermine, the recipient’s autonomy and contribution

• Finding the balance point between the benefits and liabilities of family wealth regarding the purchase of a home

Developing an entrepreneurship funding policy. Many of the families we serve highly value entrepreneurship; often, that was the engine that developed their financial wealth. Appreciating both the value of entrepreneurship and the importance of guardrails to bolster the probability of success, let’s apply this framework here. Here are the four steps in a sample entrepreneurship funding policy:

Step 1: Relevance and Purpose

We value:

• “Betting on yourself,” taking smart risks and learning perseverance, grit and persistence

• Entrepreneurship as a productive pathway to activate initiative, fun and creative expression, with the potential to lead to financial independence

• The ability to make an impact, innovate and initiate change that improves the world

• Finding creative means to educate and open up experiential learning to help the next generation rise as leaders and innovators

• Fairness in our decision-making process, including family transparency about entrepreneurship funding

• Supporting thoughtful decisions through the entrepreneurship funding process with financial guidance and education from trusted advisors

• Thoughtful planning so that family money enhances (not undermines) relationships (within the family and the couple)

Step 2: Opportunities

Partnering with family members for funding, growth and learning:

• Accelerated learning of leadership identity and skills, including how to: (1) understand the risk/reward factor in creating one’s own enterprise; (2) develop business plans, with access to consultation and mentorship inside and outside the family; (3) navigate the psychosocial impact of leading an entrepreneurial project on oneself and other close relationships (life partner, family and friends); and (4) build collaborative work relationships (partners, investors, employees, clients, etc.)

Step 3: Accountability and Responsibilities

• A formal business plan with clear objectives, financials and timelines; review of proposal by family leadership (wealth holding generation and others as applicable, including: family office executive, trustee, family council, with a clear process and criteria on who and how the final decision will be made

-

Review of the facts, expectations and predicted outcomes

-

Decide on the viability of the business plan considering: (1) review of the applicant’s business history including due diligence, credit and history of performance; (2) strengths of the recipient to execute the plan; and (3) opinion of outside advisors

• Recipient must have “skin in the game”: Demonstration of commitment: time, energy, money and openness to outside consultation (for example, mentor, coach, advisory board)

• Input and investment from unrelated parties, including:

-

Vetting by at least one outside consultant, with expertise in the specific industry of the proposed project

-

A minimum of one outside investor as a 10% or higher stakeholder

• Family leadership will determine:

-

Amount of investment (including limitation of less than 5% of the overall balance sheet)

-

How funding is given, for example, in lump sums or installments, as a loan, gift (trust distribution), investment or other

-

Amount of funding will vary, considering all the variables (for example: $1,000 for a teenager’s first venture, to $1 million for a venture capitalist and many in between)

Step 4: De-Risk

• Ongoing, active process to learn from failure, including impact on family reputation in the larger community. Evolve our policy with experiential learning

• Facing the natural consequences of failure (avoid continuous bailouts)

• Careful monitoring of how funds are used through quarterly evaluation

• Steps to monitor the quality of business partners or investors, including background checks as needed

• Discussion on the impact that family funding has on family and business relationships, including the source, such as a pot trust (assets for the benefit of multiple beneficiaries) versus an individual trust

A Word of Caution

There’s a saying that culture eats structure for breakfast.6 While the GPS is designed to help families make thoughtful, sustainable decisions, culture can quietly derail even the best frameworks. Emotional undercurrents, like a personal sense of fairness, unconscious dynamics and entrenched narratives, can halt progress. Cultural biases based on family patterns of who holds power, who has a voice, differing perspectives on the “moral compass” of wealth and insidious disempowerment of the rising generation can all undermine the successful implementation of governance.

Leveraging a decision process, like GPS, deliberately defining the why, what and how, increases the quality of our decision making. But this framework, like all decision-making models, will still be subject to the biases inherent in human decision makers (as described in the cognitive science literature). For example, cognitive biases such as confirmation bias (favoring information that supports one’s beliefs) and egocentric bias (assuming others share one’s perspective) may lead to distortions in decision making. If unexamined, these forces can erode trust and stall outcomes.

Therefore, building awareness of family culture and decision-making biases isn’t optional—it’s essential to achieving shared and lasting results.

GPS provides guidance for advisors and their clients in their thinking and construction of family policies and practices. This framework can serve not only as a compass for navigating complex family dynamics but also as a practical foundation for fostering resilience, unity and shared purpose across generations. By aligning values with actionable policies, the GPS helps families make thoughtful decisions, strengthen relationships and prepare for both opportunities and challenges ahead. With due humility, it’s essential to continually examine the influence of family culture and biases. As author Lynne Twist reminds us, money itself isn’t bad or good. Money itself doesn’t have power or lack power. It’s our interpretation of money—our interaction with it—that creates both the mischief and the opportunity for self-discovery and personal transformation.7

Endnotes

1. All case studies are shown for illustrative purposes only and are hypothetical. Any name referenced is fictional and may not be representative of other individual experiences. Information isn’t a guarantee of future results.

2. The “Smith” family and all examples are a compilation of our experiences to protect confidentiality.

3. Conversation and correspondence with Dr. Karl Pillemer, Aug. 7, 2025 and Oct. 22, 2025.

4. Dennis T. Jaffe, “Finish What You Started,” Family Business Magazine (Aug. 5, 2024).

5. For an overview of the 10×10 framework, see Stacy Allred, Joan DiFuria and Stephen Goldbart, “Building a Strong and Connected Family of Wealth: A 10×10 Learning Roadmap,” Trust & Estates (November 2021), www.wealthmanagement.com/estate-planning/ building-a-strong-and-connected-family-of-wealth.

6. Matthew Wesley, “The Blob: How culture eats structure for breakfast,” chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://jehjf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Fighting-the-Blob-Wesley-Hidden-Gem-3.pdf.

7. Lynne Twist, The Soul of Money: Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Life (Norton and Company, Reprinted 2017).