Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

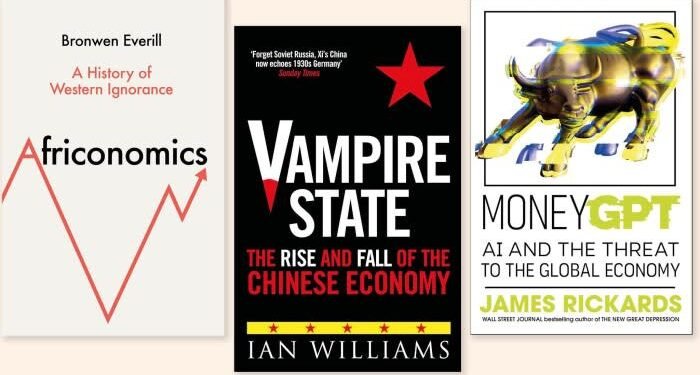

China’s economic emergence is nothing short of remarkable. Over the past four decades, it has lifted almost 800mn people out of poverty — and by some measures is already the world’s largest economy. But many now suspect that its growth model, centred around state-directed capitalism, has reached the end of the road. In Vampire State: The Rise and Fall of the Chinese Economy (Birlinn, £20) author Ian Williams — a longtime foreign correspondent, who has reported extensively from China — highlights how the Chinese Communist party has maintained a tight grip on industry, markets and entrepreneurs.

Williams argues that major policy decisions and reforms have always had the party’s continual survival as its primary motive. In effect, the Chinese economy has been largely a tool of the government, and that manipulation undermined its underlying development. Through several deeply reported chapters, he outlines how Beijing wields its influence on business: from regulatory coercion and boardroom intimidation, through even to the mysterious disappearance of entrepreneurs. He explains how rules, agreements and statistics can often be manipulated to meet the party’s ends. And how the Chinese bureaucracy is organised in Machiavellian schemes, globally and nationally — including industrial espionage — to simultaneously prop-up and maintain command of the economy.

This is a timely and important read. Williams’s sceptical prognostications about China’s economic future are hard to argue against, particularly as the state is right now struggling to revive “animal spirits” that have weakened, in part, because of President Xi Jinping’s recent clampdown on wealth-creators and tech firms. Still, with China’s dominance in emerging technologies, critical minerals and green industries, it is also difficult to write it off.

From China, to artificial intelligence. Billions of dollars are flowing into AI as companies seek to take advantage of the technology’s potential benefits for productivity. But many are worried about what the widespread use of AI might mean. In MoneyGPT: AI and the Threat to the Global Economy (Penguin Business, £18.99) James Rickards, a financial expert and investment adviser, convincingly argues that the greatest danger is not that AI malfunctions, but that it will function precisely as it was intended to. Rickards shows how the potential widespread use of AI in systemic sectors — including financial markets and nuclear defence — should worry us all.

The author slickly outlines, through an insightful hypothetical scenario, how an AI-induced financial crash might unfold in real time, from the perspective of traders, central bankers and malicious actors. It underscores how bank runs and self-reinforcing selling spirals can reach warp speed, under the influence of automated technologies. Indeed, the book makes a powerful case for better guardrails and limits around how humans might outsource decision-making as AI technology evolves.

In the UK, all eyes are on Rachel Reeves, chancellor of the exchequer, as she prepares to deliver her first Budget on October 30. The British economy is at a crossroads: growth has been poor for over a decade, demands on the state are rising, and the tax burden keeps pushing higher. In Return to Growth: How to Fix the Economy, Volume 1 (Biteback, £25) Jon Moynihan, a Conservative peer, provides a rare, detailed diagnosis and set of recommendations to get the country back on course. The author makes an often under-appreciated moral, as well as, economic argument for why growth should be central to policymakers — reiterating how the rising size of the state risks increasingly crowding out the private sector. He then incisively cuts through the UK’s tax system, regulation, government spending and civil service, outlining specific savings, reforms and tweaks that could unleash growth and reduce impediments to it. Moynihan does not mince his words, and while some may disagree with some of his assessment of Britain’s problems — and the solutions — this is a highly valuable contribution to a debate that can often be short on detail.

Finally. Bronwen Everill, a history lecturer at the University of Cambridge, in Africonomics: A History of Western Ignorance (HarperCollins, £25) provides a detailed historical account of how the west and its development agencies have approached Africa’s social and economic development over recent centuries. Everill attempts to explain through a series of case studies how western notions of trade, economic activity, debt and societal relationships may have jarred with realities on the ground. While it is indeed unclear how Africa might have emerged if local norms and cultures had emerged on their own, without western influence, Everill is convinced that the west’s economic agenda — while full of good intentions — created significant problems for the continent. A deeper exploration of the link between western-centric thinking and policy failings on the ground is certainly warranted. Still, this is a historically insightful read, with the author ultimately elevating the case for development policy to be rooted in a better understanding of local environments.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen