The 2024 Whitney Biennial is a slow burn. The often-subtle resonances between pairs or groups of works in the exhibition, Even Better Than the Real Thing (until 11 August)—curated by Chrissie Iles, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Meg Onli, a Whitney curator-at-large based in Los Angeles—are a departure from the loud themes of recent editions. It is, as Iles writes in her catalogue essay, “an exhibition made as a set of relations”.

How visitors respond to this nuanced menu of resonances may depend on what they expect from high-profile, high-stakes contemporary art shows like the Whitney Biennial. They may leave dissatisfied if they are expecting the bold statements of some recent editions: like the stark curatorial gesture of David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards’s 2022 edition, a Whitney Biennial shaped by the previous two years’ traumas and structured as a journey from darkness into light (or vice-versa); or Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks’s 2017 edition, with its mood of seething violence, epitomised by two paintings—Henry Taylor’s monumental depiction of the 2016 killing of Philando Castile by a police officer in Minnesota, the times thay aint a changing, fast enough! (2017), and Dana Schutz’s rendering of 1955 lynching victim Emmett Till, Open Casket (2017), which sparked a controversy that eventually eclipsed everything else in the show.

To be sure, this Whitney Biennial has its dramatic gestures, too. It includes a teetering replica of the White House made from dirt, Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House (2024) by Kiyan Williams, which will be reshaped by the elements over the course of the show (whose run overlaps with much of the 2024 US presidential campaign). Demian DinéYazhi’ created a bright neon sculpture warning museumgoers and passersby on the West Side Highway about the dangers of hopelessness, we must stop imagining apocalypse/genocide + we must imagine liberation (2024), which includes a subtle reference to the worst-case example of those dangers currently playing out in Gaza. Cannupa Hanska Luger contributed a work from his series of suspended installations inspired by the inverted form of a tipi—because, as he has said, “This installation is not inverted… our current world is upside down.”

Cannupa Hanska Luger, Uŋziwoslal Wašičuta (from the series Future

Ancestral Technologies), 2021–present Benjamin Sutton

But to a large extent the exhibiting artists’ engagements with the titular “real” are less about the upside-downness of our current reality and more about questions of authenticity and identity. “These artists want to destabilise the ways that identity gets flattened within the art world,” Onli says in an interview in the exhibition catalogue. “In organising this biennial, Chrissie and I have had to consider a political moment as feverish as the culture wars of the 1990s. Artists are still struggling to make sure they are not essentialised.”

Consequently, the work on view tends to evade simple summarising and reduction, instead rewarding the kind of close examination and prolonged engagement that reveals the textures and details of lived experience. In her catalogue essay, Onli says of the process of organising the exhibition that “we encountered artists addressing the multidimensionality of one’s own subjectivity and bodily materiality. This turn inward, toward the self, does not reflect a shutting out of the world—quite the opposite. It is an acknowledgment of the self and the body as malleable, citational and formed in concert with the systems that govern us.”

The bodies politic

How bodies are defined by, react against or evade systems of power may be this Whitney Biennial’s most self-evident theme—signalled elegantly and prominently in the first work many visitors will see when disembarking on the museum’s fifth floor. In Tourmaline’s video Pollinator (2022), shown here in a theatre framed by a photo-mural of a flower, the artist casts herself as both a flower and a pollinator, while also paying tribute to the activist Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992).

Nearby, the Canadian artist Jes Fan takes a much more abstract approach to rendering his own body, turning computed tomography scans of his knee, hip muscles and vertebrae into a set of 3D-printed sculptures. The reinterpretation of medical imagery turns the artist’s innards into seemingly alien forms, made all the more otherworldly by being draped with orbs of hand-blown glass.

Rose B. Simpson, Daughters: Reverence, 2024 Benjamin Sutton

In contrast, around the corner, Rose B. Simpson, an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Santa Clara in New Mexico, has created a work where bodies—a group of four ceramic figures titled Daughters: Reverence (2024)—are purposefully visible and figural. The four stylised figures are positioned looking at each other, as if holding the space against what the artist has described as the “objectification, stereotyping and the disempowering detachment of our creative selves through the ease of modern technology”.

On the museum’s sixth floor, a group of works in adjacent galleries addresses the hypervisibility and regulation of women’s bodies, epitomised by Carmen Winant’s powerful installation The last safe abortion (2023), a collection of 2,700 photographs capturing the essential care provided day after day for half a century at clinics, hospitals and other abortion providers in the US’s Midwest. The provision of such care has become much more complicated—at times even impossible—in many states ever since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022.

Detail of Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion, 2023 Benjamin Sutton

An adjacent gallery features four recent canvases by Harmony Hammond, including Patched (2022), another work made in reaction to the overturning of Roe v. Wade. At the centre of each quilt-like pattern of red and white squares are blood-stained patches of cotton, alluding to “repeated and ongoing violence against women”, in the artist’s words.

Nearby, works by the Chicago-based artists B. Ingrid Olson and Julia Phillips offer up absence and fragmentation as ways to evade violence and control. “Evoking the body without the depiction of one has become one of several strategies through which artists attempt to thwart such probing looks and scrutiny,” Onli writes in her catalogue essay.

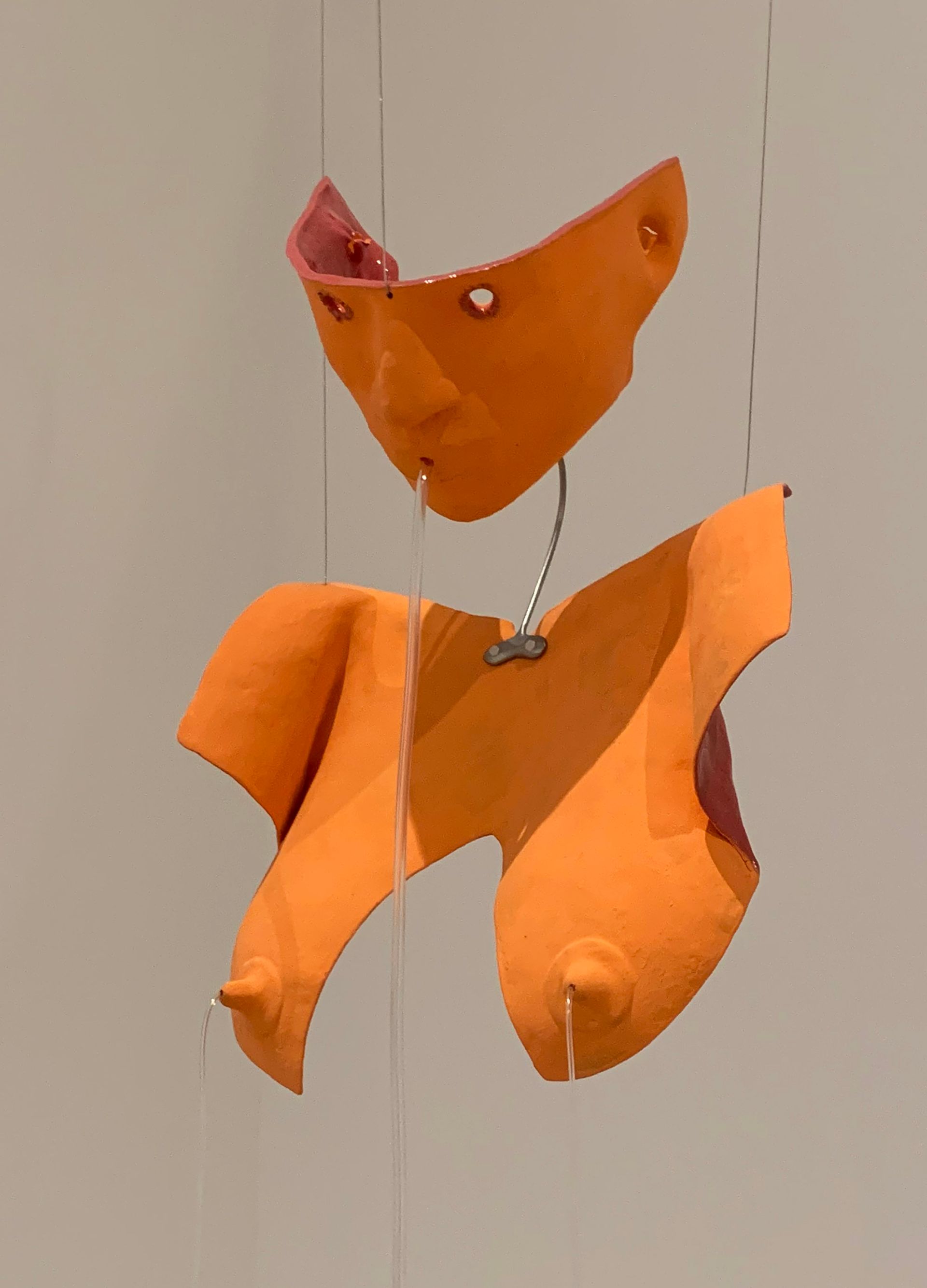

Julia Phillips, Nourisher, 2022 Benjamin Sutton

Phillips’s delicate ceramic sculptures include the chest and partial face of a nursing woman, Nourisher (2022) and Mediator (2020), in which two ceramic casts of chests rendered in contrasting hues face each other across a microphone stand. The figures, exquisitely detailed while also generic, use fragmented bodies as a kind of prompt. “Letting viewers fill in the blanks hopefully allows them to adjust the works to fit their own realities and imaginations,” the artist has said.

In Olson’s Dura Pictures series, the artist photographs and fragments her own body in her studio, such that individual limbs and body parts are visible in disorienting compositions. The accompanying set of 30 sculptures, Proto Coda, Index (2016-22), consists of small containers for individual body parts—something like what might happen if Ikea started manufacturing armour. Two small concave ramps on the gallery floor are the perfect size to nestle one’s heels in; a half-dome on the adjacent wall describes the negative space of the crown of someone’s head. Olson’s abstract cases for body parts obliquely make the point that bodies are not all cast from the same mould.

Ageing wonders

While human bodies come in all shapes and sizes, they share a susceptibility to time. One gallery on the museum’s sixth floor brings together works by three artists that more or less overtly address topics of self-preservation and ageing. Carolyn Lazard’s maze-like arrangement of medicine cabinets filled with vaseline, Toilette (2024), hints at the private, domestic rituals of cleaning and self-care. On an adjacent wall, Mary Kelly’s ten-panel work Lacunae (2023) takes the form of a calendar that stretches across the entire gallery wall. On it she repeatedly noted her age, as well as the names and ages of friends at the times of their deaths. The resulting composition records the slow creep of death in a manner that is deeply personal yet universal.

Sharon Hayes, Ricerche: four, 2024 Benjamin Sutton

That universality is at play on the other side of the room in Sharon Hayes’s beautiful documentary Ricerche: four (2024). The 80-minute video consists of interviews Hayes conducted with three groups of elderly LGBTQIA individuals, who reflect on their lives and the importance of their chosen communities at this advanced stage of life.

History, herstory, our-story

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight is a trope in the many works that focus on history and the use of historical figures, often in films and videos. Isaac Julien’s 2022 five-channel black-and-white video installation Once Again… (Statues Never Die)—concurrently on view at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht (until 17 August)—provides a 30-minute anticolonial institutional critique with an eye towards museum restitution. This is achieved through exploring the relationship and eventual falling out of the Harlem Renaissance philosopher Alain Locke and the chemist Albert C. Barnes. (Locke studied Barnes’s African art collection at the Barnes Foundation, which would much later commission Julien’s piece.) The videos reimagine, in part, the two men’s debates about African art, with sculptures by Richmond Barthé and Matthew Angelo Harrison interspersed throughout the room for added effect.

Isaac Julien, Once Again… (Statues Never Die), 2022 Benjamin Sutton

Also interested in the history of colonialism, Ligia Lewis filmed A Plot A Scandal (2023) in Rimini, Italy—for the artist, its historic centre encapsulates “Eurocentric ideals of (white) man’s dominion over the land”. With that backdrop, Lewis focuses on the stories of three people: the 17th-century English philosopher John Locke (who justified the existence of slavery and defended European colonisation), José Antonio Aponte (an artist and revolutionary who led a significant slave rebellion in Cuba in 1812) and the artist’s own great-grandmother.

Another form of institutional critique—but in a more physical form and, this time, directed at the US as a whole—is Kiyan Williams’s Ruins of Empire II. The monumental earthen sculpture of the White House façade slumps and sinks into the floor on a Whitney terrace, an upside-down US flag flying atop its roof, while a shiny aluminium sculpture of Marsha P. Johnson looks on from the side. Perhaps there is a note of optimism here. As the elements inevitably break down the already teetering seat of US executive power, the defiant drag queen and activist will remain unscathed.

Kiyan Williams, Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the

Master’s House (2024, left) and Statue of Freedom (Marsha P. Johnson) (2024, right) Benjamin Sutton

In an appreciation of a lesser-known historical figure, Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich focuses on the 20th-century Martinican writer and feminist Suzanne Césaire, who pioneered the idea of Négritude—a uniquely Black Caribbean form of anticolonial surrealism. Césaire’s husband, Aimé Césaire, and associates André Breton and Wifredo Lam often get all the credit for ideas she introduced them to, and Hunt-Ehrlich points to the irony of such a significant figure being forgotten in her film Too Bright to See (2023-24).

Moving further east across the globe, Diane Severin Nguyen’s first feature-length film, In Her Time (Iris’s Version) (2023-24), follows a Chinese actress preparing to star in a movie about the Nanjing Massacre—a 1937 genocide and mass rape perpetrated by the Japanese army during the Second World War that killed 200,000 Chinese civilians. As the actress rehearses for the part, particularly for her death onscreen, the lines blur between perpetrator and victim, power and weakness, performance and reality, propaganda and truth.

Can’t stop the music

An invisible but recurring theme, music in many different forms permeates several spaces and projects. Clarissa Tossin’s film Mojo’q che b’ixan ri ixkanulab’/Antes de que los volcanes canten/Before the Volcanoes Sing (2022) incorporates footage of people playing replicas of traditional Mayan wind instruments—the objects themselves are displayed just outside the screening room. A kind of extension of Isaac Julien’s institutional critique, the project uses 3D-printed versions of the intricately carved instruments because the originals are all owned by museums, unavailable to descendants of the people who made them to use for their intended purpose.

Another silencing of music can be found in what is perhaps the most delightful-yet-profound project at the biennial, TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME) (2023-24) by Nikita Gale—an artist with a background in archaeology who has found unique ways of using music in sculptural works. In a darkened room, a player piano has been programmed to perform Scott Joplin’s The Entertainer, a classic ragtime tune—except that the strings are muted, so that when one would normally hear individual notes, there are only the taps of the mechanics of the instrument. The absence of both a human musician and the actual music is further accentuated by an instantly recognisable rhythm of the keys and hammers. (Joplin, dubbed the “King of Ragtime” in the late 19th century, was himself largely forgotten until his music was “rediscovered” in the 1970s.)

Nikita Gale, TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME), 2023–24 Benjamin Sutton

In a further dismantling of a musical instrument, K.R.M. Mooney’s wall sculptures are cast from parts of instruments and other objects that produce sound, like amplifiers. Given their materials, the sculptures are made to transform over time with changes in humidity and temperature.

From objects that make (or once made) music to the sound itself, as part of the biennial this year, the musician JJJJJerome Ellis—the name’s styling references the artist’s stutter—was invited to create a score for the entire exhibition, taking inspiration from the works, spaces and sounds experienced there. Ellis is currently working on the composition, which will be displayed as drawings and notations as it develops, culminating in a live performance in August.

Picking up pieces

Ser Serpas, taken through back entrances subtle fate matching

matte thing soiled…, 2024 Benjamin Sutton

Assemblage has long been a fixture of the biennial, and this year is no exception, with a number of artists using found objects in their work. But for Ser Serpas, “assemblage is the aftermath” of the performance of art-making, as seen in her installation in the lobby gallery, taken through back entrances… (2024). The New York-based artist scoured the streets of Brooklyn for objects she could recombine into sculptures that hold a tension between balance and collapse—a portrait of both the city as a whole and the artist as an individual.

Karyn Olivier, meanwhile, picks her found materials with more of a theme in mind. In her sculpture How Many Ways Can You Disappear (2021), she used driftwood, buoys, fishing rope and lobster traps as stand-ins for the sea, migration and the legacies and many histories of enslaved human beings forcefully transported over vast bodies of water.

Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio, Paloma Blanca Deja Volar / White Dove Let Us Fly, 2024 Benjamin Sutton

Finally, although the Los Angeles-based artist Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s Paloma Blanca Deja Volar/White Dove Let us Fly (2024) can hardly be called assemblage, his use of archival documents and tree amber provides for unique sculptures that (like K.R.M. Mooney’s works) morph with changes in temperature and light. Aparicio connects the history of amber-producing trees in Southern California with that of Latin American migrant workers, and the papers encased in amber moving slowly through the sculpture are reminiscent of how an individual’s memories and trauma shift with the passing years.

As it changes over the course of the show, Aparicio’s piece—like so many works in this Whitney Biennial—defies simple categorisation or static meaning and merits close, patient and repeated observation. Or, as Iles puts it in the catalogue, “these artists are troubling notions of fixity and objecthood in ways that remind us that the body itself is unfixed and changes over time”.

- Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, until 11 August, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York