Budget 2024 announced this week underlined the poor fiscal state the government finds itself in, and the dipping into the Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account to the tune of R150 billion is concerning, as it seems to be the only remaining pot of gold the government has access to.

Although it is common for countries worldwide to use foreign exchange profits, withdrawals need to be used productively.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Using the R150 billion will provide temporary relief, but will be wasted if the core structural problems that caused the country’s debt to increase to the extent it has are not addressed effectively. Think electricity supply, logistics, corruption, and poor financial management of government, of state entities and local governments.

Read: #Budget2024 in a nutshell: No major tax hikes

South Africa needs a legislative debt ceiling to limit the debt the country can absorb.

The investment group Charles Schwab highlights that only a few countries have such ceilings.

These include the United States, Denmark, Poland, Kenya, Malaysia, Namibia and Pakistan. The US and Denmark have absolute ceilings, which means their debt cannot exceed a certain amount. The other countries’ ceiling is a percentage of GDP.

| Countries with debt ceilings | Ceiling |

| USA | A fixed amount of $31.4 trillion |

| Denmark | A fixed amount of $180 billion |

| Poland | Capped spending to 60% of GDP |

| Kenya | 55% of GDP |

| Malaysia | 66% of GDP |

| Namibia | 35% of GDP (the current ratio is 72%) |

| Pakistan | 60% of GDP (the current ratio is 75%) |

Apart from Denmark, it seems as if not many other countries stick to the ceilings, but it at least provides a target.

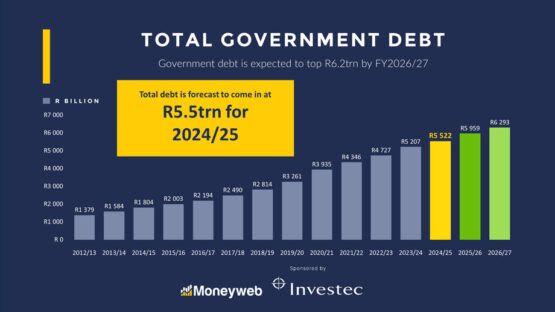

South Africa’s debt currently stands at around R5.2 trillion or 74% of GDP, and it is already unaffordable as one of every five rands of revenue is consumed by interest payments.

Source: National Treasury

The debt is set to rise to R6.3 trillion by 2027, or 75% of GDP, and according to National Treasury, this is the level at which the ratio will stabilise before declining.

History suggests that it is unlikely.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

In 2018, when Cyril Ramaphosa became president, South Africa’s debt was R2.3 trillion or 49% of GDP.

At the time, National Treasury foresaw it would stabilise at 53% in 2024, which was spectacularly missed.

Covid did have an impact, but it still means South Africa’s debt has spiked 126% in only six years, which reflects the extent of the problem.

A recent study by the World Bank suggests that the maximum threshold for developing countries is around 64%. If the ratio is higher, it starts to impact economic growth negatively.

It would be appropriate for South Africa to set a debt ceiling of around 64% of GDP and formulate a roadmap to achieve this target.

It could only happen by taking unpopular decisions such as privatising underperforming state-owned enterprises such as Eskom and Transnet and using the proceeds to repay debt.

It is probably wishful thinking, but if the current trend continues, the fiscal cliff is approaching faster than we think.