Indira Puri, author of the groundbreaking study “Simplicity and Risk,” published in the April 2025 issue of the Journal of Finance, challenges traditional finance models by demonstrating that humans aren’t just risk-averse, they are also complexity-averse (“simplicity is a unique component of choice”). This discovery reshapes our understanding of decision-making and portfolio design.

Puri tested whether people value simplicity when making risky choices, even when statistical outcomes (like mean or variance) are identical. Her tests presented participants with choices between lotteries of varying complexity while keeping key statistical moments (like expected value) constant. Her key questions were:

Puri’s experiments compared behavior against models like Expected Utility Theory (a decision-making model where rational choices are made by maximizing the expected “utility” of an outcome, considering both objective and subjective probabilities, especially in situations involving uncertainty), Prospect Theory (a behavioral economics theory explaining how people make decisions under risk, highlighting that individuals value gains and losses differently, often deviating from rational behavior) and rational inattention (the idea that economic decision-makers cannot absorb all available information but can choose which pieces of information to process).

Here is a summary of Puri’s key findings:

Models that ignore complexity conflict between risk aversion and complexity aversion. Behavioral models failed to explain complexity-driven risk premia—subjects actively paid to avoid complexity. They didn’t just tune it out.

Unsurprisingly, complexity led to more mistakes—subjects objectively chose worse options seven times more frequently in complex setups versus simple ones. As such, complexity increased risk premiums: Participants demanded higher compensation for risks presented in complex formats, even when the statistical moments (like mean and variance) were identical to simpler alternatives.

Additionally, simplicity preference was predictable—choices systematically shifted toward simpler frames when complexity increased, aligning with a new “simplicity axiom” proposed in the paper.

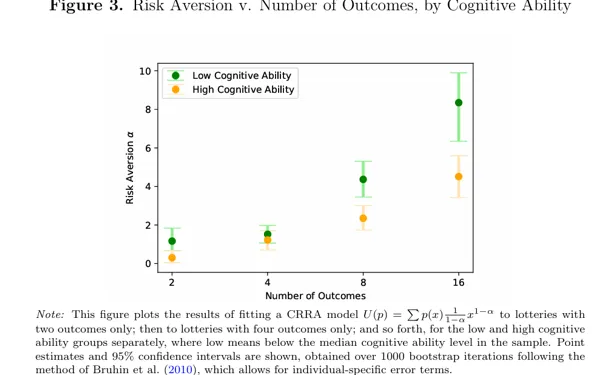

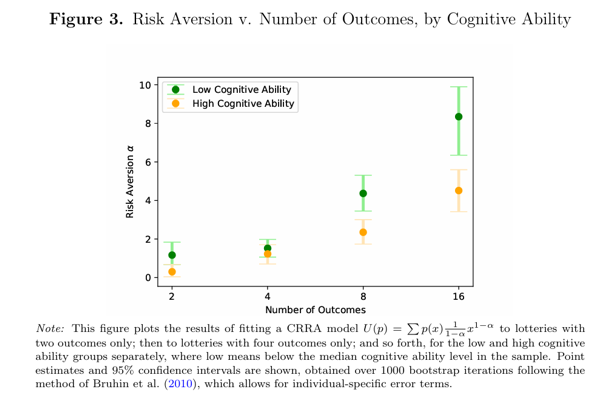

Finally, cognitive ability and complexity aversion are correlated—lower cognitive ability (measured via tests) correlated with stronger complexity aversion, suggesting simpler portfolios may better serve some investors. Prior research has shown that people with higher cognitive ability are less risk-averse.

Her findings led Puri to conclude that existing financial models are insufficient—none of the traditional models, including expected utility theory, cumulative prospect theory, prospect theory, rational inattention, salience theory (decision-makers’ attention is directed to the most salient payoffs of the lotteries available for choice) or probability weighting (the tendency for individuals to over-weight low probability events, while also under-weighting high probability outcomes) fully captured the experimental findings related to simplicity preference.

Takeaways

Puri’s findings challenge traditional finance models and suggest that humans are both risk-averse and complexity-averse, which has significant implications for understanding decision-making in financial markets and portfolio design. She showed that complexity is a hidden cost, as investors systematically overpay to avoid it, and traditional portfolio theory ignores this bias. By highlighting the cognitive aspects of risk perception, she added a new dimension to portfolio diversification theory, suggesting that effective diversification isn’t just about statistical risk reduction but also about creating portfolios that investors can understand and stick with over the long term.

My almost 30 years of advising investors have taught me that while there might be an economically right portfolio (one that is hyper-diversified across as many unique sources of risk that meet your investment criteria), there is no single psychologically right portfolio. Thus, the right one for each client is the one that they are most likely to stick with. The reason is that behavioral errors such as tracking variance regret (when a more diversified portfolio underperforms a simple total market portfolio) and recency bias can lead investors to abandon even well-thought-out plans, leading to poor performance. Puri showed that complexity aversion can also lead to behavioral mistakes.

To adapt, financial advisors can educate clients about complexity aversion to mitigate its effects and avoid the mistakes caused by simplicity aversion (such as less diversified and, therefore, riskier portfolios, ones with more tail risk). However, Puri’s findings suggest that simpler portfolio structures may be preferable, especially for investors with lower cognitive abilities, challenging the concept that more complex, highly optimized portfolios are always better.

Implications for Advisors and Portfolio Construction

Tailor Complexity to Cognitive Profiles. Identify clients prone to complexity aversion and offer them streamlined options to prevent the mistake of overpaying for simplicity.

Simplify Client Choices. Presenting portfolios in simpler formats (e.g., “60% stocks/40% bonds” vs. multi-factor optimizations) may reduce perceived risk and improve decision quality.

Avoid Opaque Products. Structured notes, leveraged ETFs, long-short factor strategies, or multi-layer derivatives might trigger hidden complexity premiums.