Marseille’s Art-o-rama contemporary art fair, which opened its 17th edition yesterday (until 3 September), marks the last hurrah of the art world summer, as August on the French Riviera draws to a close. Featuring around 40 mostly emerging galleries from Europe, the US and Latin America in the former tobacco factory-turned cultural complex Friche la Belle de Mai, it is host to a crowd that appears relaxed (doors don’t even open until 2pm), tanned and convivial.

This sunny atmosphere takes on a more macabre tone at the stand of Ginny on Frederick gallery in London, which shows a solo presentation of oil paintings by the UK artist Alex Margo Arden (£2,500-£3,750). These depict moments from the police crime scene of the death of the cinematographer Halyna Hutchins, who was fatally shot in 2021 when a gun held by the actor Alec Baldwin went off while they were filming a Western movie, Rust, in New Mexico. Baldwin claims that he was not aware the gun was loaded with a live round, nor, he also claims, did he pull its trigger.

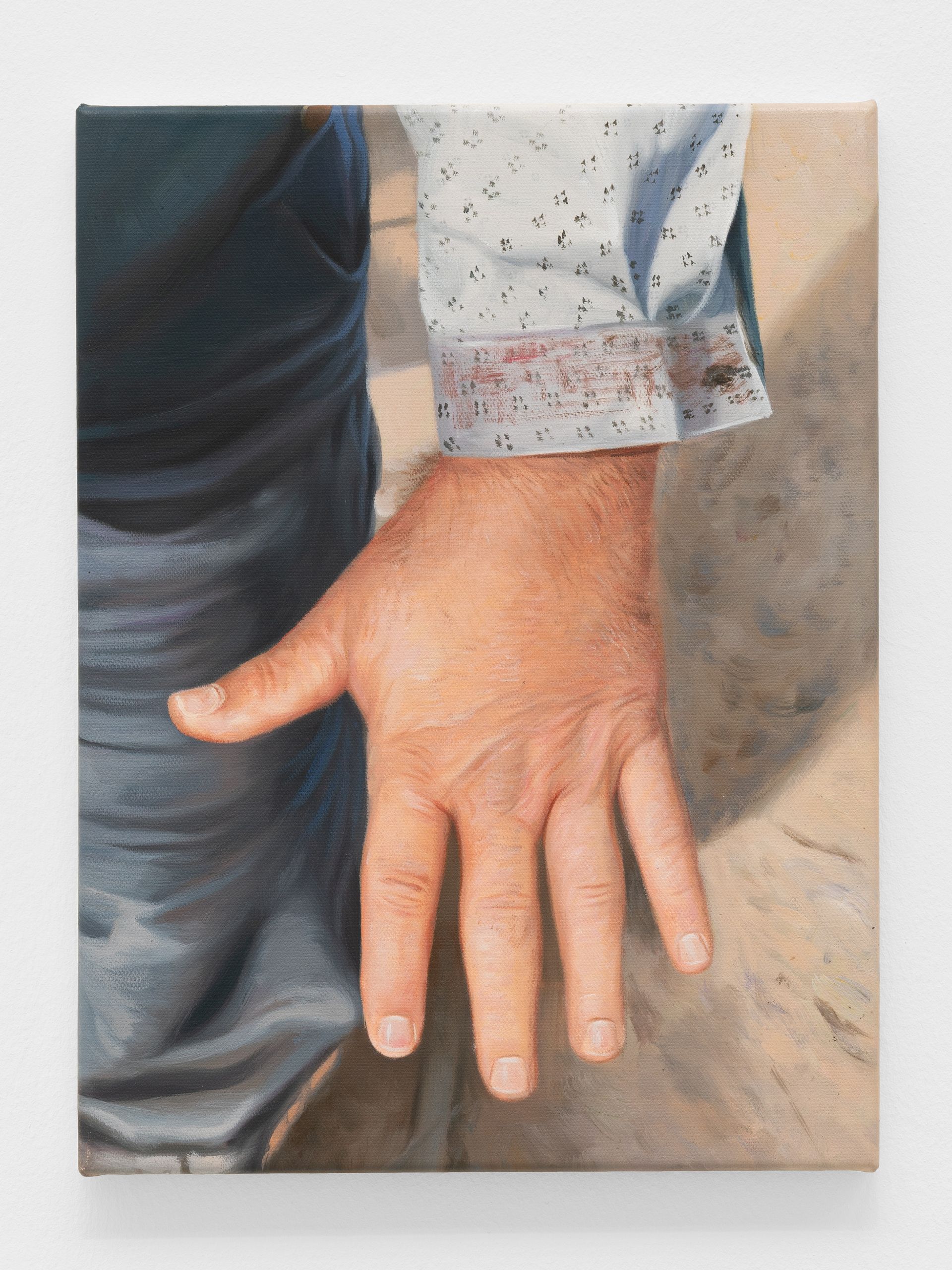

The context of these paintings—which depict police cars parked outside the film set, a gun in an evidence box, and a solitary arm with reddish marks around its shirt sleeve—is made clear by an accompanying text written by Arden, that details the incident and ensuing legal trials. Prosecutors in New Mexico dropped involuntary manslaughter charges against Baldwin in April this year, after Arden had finished the paintings. Meanwhile the trial of the film crew’s armourer, responsible for the gun, Hannah Gutierrez-Reid, who has pled not guilty to involuntary manslaughter, is scheduled for later this year.

The events, covered widely in the media, raise serious questions of who to blame? The film industry? The US’s deeply entrenched gun culture? No one? This dilemma is encapsulated by one word, written by Arden three times across the walls of Ginny on Frederick’s stand like a mantra: “Responsibility, responsibility responsibility”.

Alex Margo Arden’s His Hand (I) (2023)

Courtesy of Ginny on Frederick

“Since the earliest days of cinema, there have been huge deadly disasters during filming, especially in the epics shot in the 1920s and 1930s,” Arden says. “There are instances of a studio shooting a drowning scene, and in doing so accidentally killing 15 extras—and then just bringing in 15 more people to complete the scene. Actual death on a film set collapses the distinction between reality and artifice in the most horrifying way.”

This word “responsibility” pertains equally to another question raised by these paintings: how should artists portray scenes of real-life tragedy—if at all? Importantly, Arden has elected not to depict any full human figures, especially that of Hutchins post mortem.

Arden’s careful approach to such charged subject matter differs from other, more explicit artistic depictions of real-life tragedy. The most prolific example of this in recent years might well be Dana Schutz’s painting of the corpse of Emmett Till, a Black child who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. The work was shown at the 2017 Whitney Biennial and a media storm ensued over the ethics of this image being used in an exhibition, as well as by Schutz (a white woman).

Nonetheless, Arden does not shy away from asking difficult questions around this subject. “I’m interested in questions of responsibility, what it means to have embedded myself, as an artist, into the narrative of this trial by remaking parts of the evidence for public consumption. This trial was so sensationalised in the media, and all that coverage inevitably skewed the reception of the facts. Opinions of blame and justice can be understood as the interpretations of multiple people,” she says. (The first conviction in the legal proceedings around Hutchins’s death came on 31 March when Dave Halls, first assistant director on Rust, received a six-month suspended sentence after making a plea deal admitting a charge of negligent use of a deadly weapon.)

Arden says she was able to depict so much evidence because the Santa Fe police department unusually decided to upload hundreds of images of the crime scene into a publicly available Google drive; the drive was later taken down. To complicate the idea of responsibility in her work even further, Arden has employed professional painters to execute these works, “distancing them from her hands”, she says.

“These works aren’t here to provide a morality lesson, but they do raise some important points about Hollywood and gun safety, as well as conceptual ones around painting and labour processes in art,” says Freddie Powell, the director of Ginny on Frederick. The gallery, currently housed in a sandwich shop in Farringdon, east London, is moving to a new location nearby in early October.

Attendees of the 17th edition of Art-o-rama in Marseille

© Margot Montigny

Ginny on Frederick’s stand is one of several curatorially ambitious presentations from young galleries at Art-o-rama, which charges relatively low stand fees, at €3,000. According to the director of Fraeme, Véronique Collard Bovy, the organisation that runs the fair’s venue, the rest of Art-o-rama’s costs are covered by various state cultural bodies and external partners.

“The low costs definitely encourage young galleries like us to bring more experimental work,” says Alex Harrison, the director of Public gallery in London, which is showing a solo presentation of ceramic works, paintings and sculptures by the French artist Nils Alix Tabeling. Meanwhile, Sans Titre gallery from Paris has brought a 15-metre-long fabric work by the Palestinian artist Aysha E Arar, which comments on the Israeli occupation of homeland.

So does Art-o-rama’s combination of low financial risk and relaxed fair-goers lead to sales? “I’ve had fewer conversations than at some other fairs,” Powell says. But that hasn’t stopped some of Arden’s works from shifting—three in total have so far sold, including one to the Marseille-based choreographer Arthur Harel.

As Collard Bovy says: “A collector recently told me, at Art-o-rama, I consider art first and the market second, and we intend to keep it this way.”