The poetry of the Dalit revolutionary Poykayil Appachan has long been a touchpoint for the artist Sajan Mani, whose work examines the caste system and the oppression of marginalised groups in India. One poem by Appachan, about the darkly plumed pariah kite, inspires the title of Mani’s first solo show in India, Multiple Legs of a Historically Wing-Chopped Bird at Shrine Empire gallery in New Delhi. The term pariah “connotes the degradation associated with the caste system”, writes the academic Cleo Roberts-Komireddi in her essay accompanying the show.

The exhibition delves into the histories of Kerala, where the artist is from. “You can see my practice as an act of history-making,” Mani says. “From the different works that are shown in the exhibition, one can go through the layers of history that were either not captured accurately or erased.”

From Sajan Mani’s 2023 series Transmigratory whispers

Courtesy of the artist and Shrine Empire

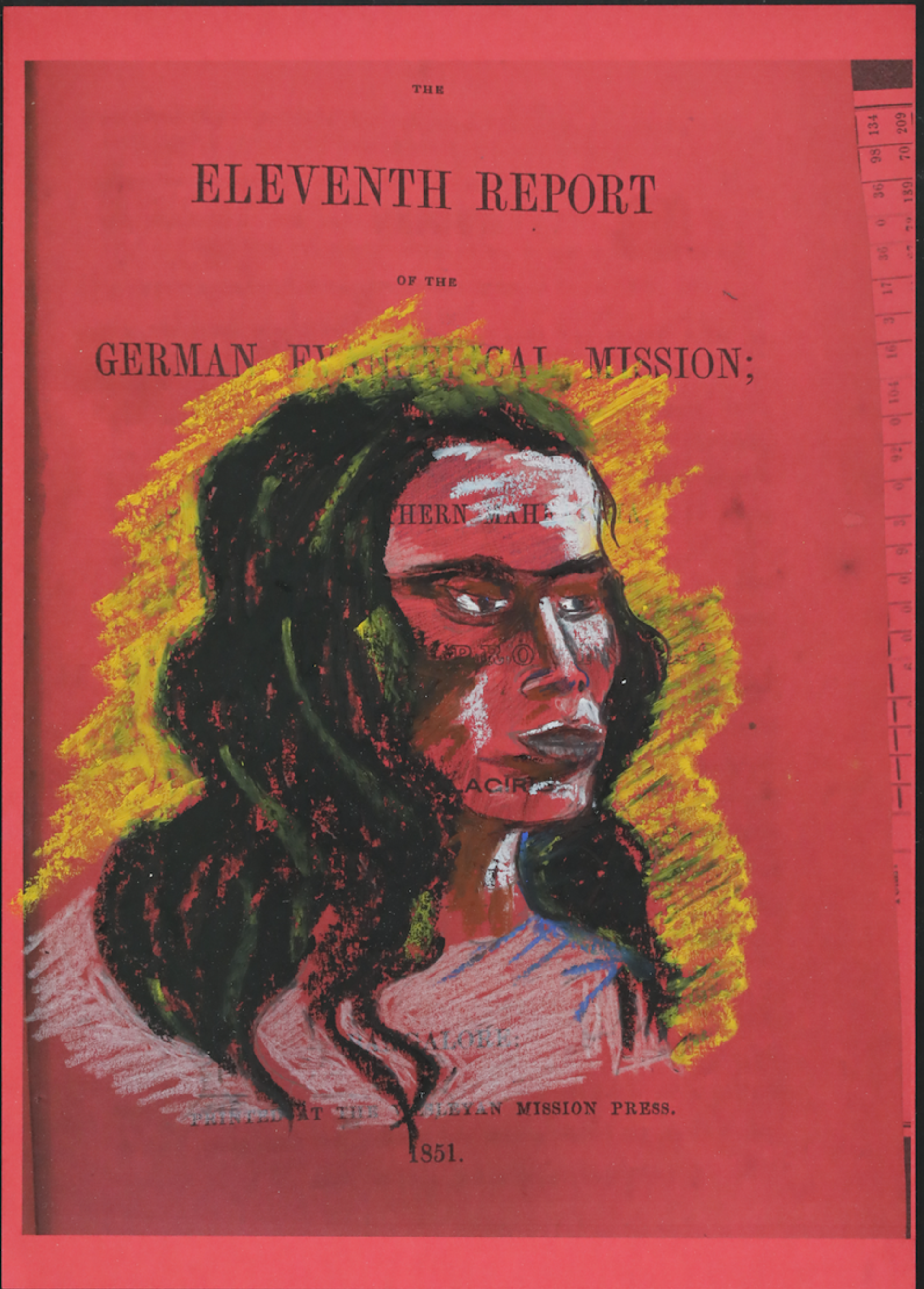

Entering the gallery, one first encounters a set of drawings hung on a bright red wall. The series, titled Transmigratory whispers, shows Dalit figures painted on archived pages of European missionary reports and dictionaries. Notably, Dalits were strictly forbidden to read and write, or to venture out of the social caste hierarchy. Mani elaborates: “Through a conscious act, I chose these images from a German anthropologist who came to Kerala in the 1920s; his name is Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt. Later he became a Nazi and a racial theorist. He took a lot of photographs of Dalit and Indigenous people from Kerala and their lives, so I, too, was looking into these archives and consciously choosing the life of oppressed people, and then foregrounding that into this time and space.”

Another room in the gallery displays works on thick rubber sheets. This is yet another endeavour of history-making for Mani, whose parents were rubber tappers. “Rubber is a very important medium for me. My childhood memories are filled with the smell, the elasticity of rubber”, he says.

According to Anahita Tanjea, the co-founder of Shrine Empire, “Sajan’s unique use of natural rubber sheets comes from his family working in the rubber plantations. The use of the medium is also a way to connect back to his roots and family history, along with using it as a metaphor and it becoming a witness to history and its people”.

For the show, Mani has also transferred pages from the first dictionary manuscript written in Malayalam, which he sourced from the Tübingen University archives in Germany. “I am rejecting the so-called established post-colonial studies and theories which normally, in India, was about kings and princes, and the Kohinoor,” he says. “It was never about the people who made these”. He uses these very archives in his works to rewrite the erased or the missing parts.

The exhibition opened with a public performance by Mani in the gallery space in which he made marks on the wall and floor. During the performance, the artist moved his body with fluidity, in reference to a river—he was born and grew up in a village on the banks of a river in Kannur.

The motif of water also speaks to the environmental concerns entangled in this work. Mani explains: “The river also creates a vast area of muddy land. Kallen Pokkudan, a Dalit environmental activist in Kerala who held Indigenous knowledge, planted mangroves all over the shores of the river. I bring these themes in my work. Climate justice should not be only surrounded by Western questions and the polar bears or the glaciers alone.”

Although the performance has been extensively documented for reference, the marks on the wall in the gallery remain through the duration of the show for future visitors to experience. “The residue on the floor and the smell of the soot continue to linger, giving a glimpse into the performance throughout the show”, says Shefali Somani, the co-founder of Shrine Empire.

Mani’s past performances have also referenced a ritual dance form called theyyam, which carries with it a history of resistance. It is said that during the ritual, lower-caste people embody gods. Participants predominantly use colours such as red and black. Some theyyam songs contain explicitly anti-caste and revolutionary elements. And the mark making on the walls as part of the performance is an intertwined act of drawing as writing and writing as drawing. “I felt like a collective body rather than a single body”, he says.

• Multiple Legs of a Historically Wing-Chopped Bird, Shrine Empire, New Delhi, until 22 January 2025