The Rubin Museum will close its Manhattan galleries in October, but will continue to champion the art of the Himalayas through an expansive model that includes grant-making and continuing its active loan programme.

Jorrit Britschgi, the museum’s executive director, said that a lot of thought, planning, and analysis led to the decision to transition into a museum without walls and expand their reach globally. The museum began to make this move by implementing various digital strategies. “We were able to test many of them already with the pandemic,” Britschgi says.

For instance, Project Himalayan Art—the museum’s online resource—has become a multimedia treasure trove for educators and the curious alike. Its Mindfulness Meditation podcast, launched in 2020, has been downloaded by users from 189 countries. (Its other podcast, Awaken, was a Webby Awards honouree.)

The Rubin, funded by Donald and Shelley Rubin, opened in a former department stores in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighbourhood in 2004 with more than 3,000 objects centred largely around art from the Tibetan Plateau. It established its presence over the years with a series of memorable exhibitions and innovative programmes from displaying The Red Book—the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s legendary and rarely seen illustrated manuscript—to the popular Dream-overs where adult participants camped out near a work of choice while listening to lullabies and bedtime lectures about dreams.

Even before the onset of Covid-19, Britschgi says, the museum’s leaders were considering different ways they could use the collection and deploy their financial assets to collaborate with other organisations to tell the story of Himalayan art and culture.

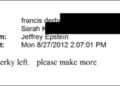

Installation view of the Pavilion of Nepal at the 59th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2022. Photo: Riccardo Tosetto, courtesy of Tsherin Sherpa and Rossi & Rossi

In many respects, the Rubin has already implemented its global vision. For the 2022 Venice Biennale, it provided lead support for the inaugural Nepal pavilion. Earlier that year, it returned an artefact in its collection when it was discovered that it had been looted from Itumbaha, one of the oldest monasteries in Kathmandu.

Britschgi points out that the new model the museum is pursuing is not related to the repatriation issue. “If there are other pieces that should be sent back, we will do that,” he says. When it came to Itumbaha, the museum was presented with an additional opportunity to help that community establish its own museum. “It was our response to what the community wanted,” he says. “We stepped in with a meaningful contribution … and going forward we will be entering many more collaborations in the Himalayas that go beyond repatriation.”

The Rubin also successfully recreated the Mandala Lab, a fixture of its New York space, as an interactive installation in a park in Bilbao—further proof that the museum can create projects for public spaces. “We have been able to reach people who wouldn’t typically enter a museum and make them familiar with our work and what we stand for,” Britschgi says.

Installation view of the Rubin Museum’s exhibition Gateway to Himalayan Art at Lehigh University Art Galleries (31 January-26 May 2023). Photo by Ryan Hulvat, courtesy of Lehigh University Art Galleries

Applications for the Rubin’s new grant programme will open in March, with details on the process to be posted online at that time. “We want to be responsive,” says Britschgi, adding that it will also be a learning process for the organisation on how to effectively step in. “There are two angles; how do we enable scholarship and new research, and how can we support creative exploration and dialogue.” In addition to this two-pronged approach, the Rubin is also establishing an awards programme for artists from the region.

The decision to sell the building allows the museum to spread awareness of its work around the globe. “This is a choice that the Rubin is making from a position of strength.” Britschgi says.

There is one beloved treasure from the museum that will find a permanent home in New York City—the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room. The Rubin is still working out the details and will announce a location in the coming months.