Robert Irwin, a pioneering figure in California’s Light and Space movement and a hugely influential maker of experiential, minimal, sometimes site-specific and often deeply ephemeral works, has died, aged 95. Irwin’s death, at Scripps Memorial Hospital, San Diego, was caused by heart failure, according to Arne Glimcher, the founder and chairman of Pace Gallery, which has represented the artist since 1966.

“In my long career, I have been privileged to work with some of the greatest artists of the 20th century and develop deep friendships with them,” Glimcher said, “but none greater or closer than Robert Irwin. In our 57-year relationship, his art and philosophy have extended my perception, shaped my taste and made me realise what art could be.”

Robert Irwin, untitled (dawn to dusk), 2016 © 2023 Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Permanent collection, The Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Photo by Alex Marks, courtesy The Chinati Foundation

Irwin contributed large-scale design work for galleries and landscape spaces at museums across the United States. These include at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where he created the terraces and gardens, circles within circles of tightly knotted topiary, around Richard Meier’s sprawling hilltop building in 1997—and went on working with the evolving gardens for another quarter-century—and a 2005 project at Dia:Beacon, a massive reconditioned factory building in Upstate New York.

In 2017, the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, opened untitled (dawn to dusk), a freestanding structure and the largest piece Irwin ever made. It took 17 years to make and saw Irwin—in his mid-80s by the time it opened—transform a former army hospital on Chinati’s campus into a 10,000 sq. ft, horseshoe-shaped installation that progresses from light to dark. Windows installed at eye level reveal a thin strip of landscape and a vast expanse of the Texas sky.

Robert Irwin (left) and Arne Glimcher, founder and chairman of Pace Gallery, 2022 Courtesy Pace Gallery

The loosely aligned Light and Space movement—whose proponents included Irwin and James Turrell, and which developed around a very 1960s California focus on space and transcendence—found its name when the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) hosted Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space: Four Artists (1971), featuring the work of Irwin, Peter Alexander, Larry Bell and Craig Kauffman. Forty years later, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) presented a landmark survey of the movement, Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface (2011).

Irwin’s works with light break down into two main types: those that manage natural light—sometimes through window openings, sometimes through the subtlest of net-like scrims—and installations built on fluorescence.

Peter Plagens wrote in Artforum that, at the 1971 UCLA show, Irwin’s stairwell installation was “by far the most ambitious work, because in this crowd it is the least material (material meaning ‘gear’ or ‘glass’ or ‘plastic’) and takes the most chances: the dense, translucent net fitted over the staircase to divert the changing sunlight, gives one almost nothing, and demands the viewer work for sensation”.

The “dense, translucent net” of Irwin’s stairwell piece became a calling card in some of his grandest, yet most minimal, pieces. An archetypical work is his Black rectangle—Natural light (1977), created for the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 2013, Donna De Salvo, chief curator and deputy director for programmes at the Whitney, told The Art Newspaper that the highlight of her year had been “the honour of working with Robert Irwin on the re-installation of his Scrim veil—Black rectangle—Natural light … 36 years after it was first presented at the Whitney”. The ephemeral nature of some of Irwin‘s works—in 1976 at the Venice Biennale, he made a square piece in string on the ground to capture the slowly moving shadow of a nearby tree—was emphasised by the fact that the 2013 Whitney installation came down less than four months later, just a year before the museum left its Marcel Breuer-designed home on the corner of Madison Avenue and 75th Street and moved downtown to a new building on Gansevoort Street.

Robert Irwin, Full Room Skylight–Scrim V–Dia Beacon (1972/2022) at Dia:Beacon, New York Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation

Irwin’s untitled (dawn to dusk) at the Chinati Foundation was an exemplar of his work with light and apertures, as was his first permanent museum installation, 1° 2° 3° 4° (1997), for MCASD (where he was an artist in residence), set in the museum’s oceanview gallery. The work’s title refers to four dimensions—height, width, depth and time; time being aligned with the movement of the sun as it plays on three rectangles that Irwin cut in the gallery’s tinted windows (lighter blue against darker blue), through which the sea breeze blows. It is a truly experiential space: at once playful, simple and profound.

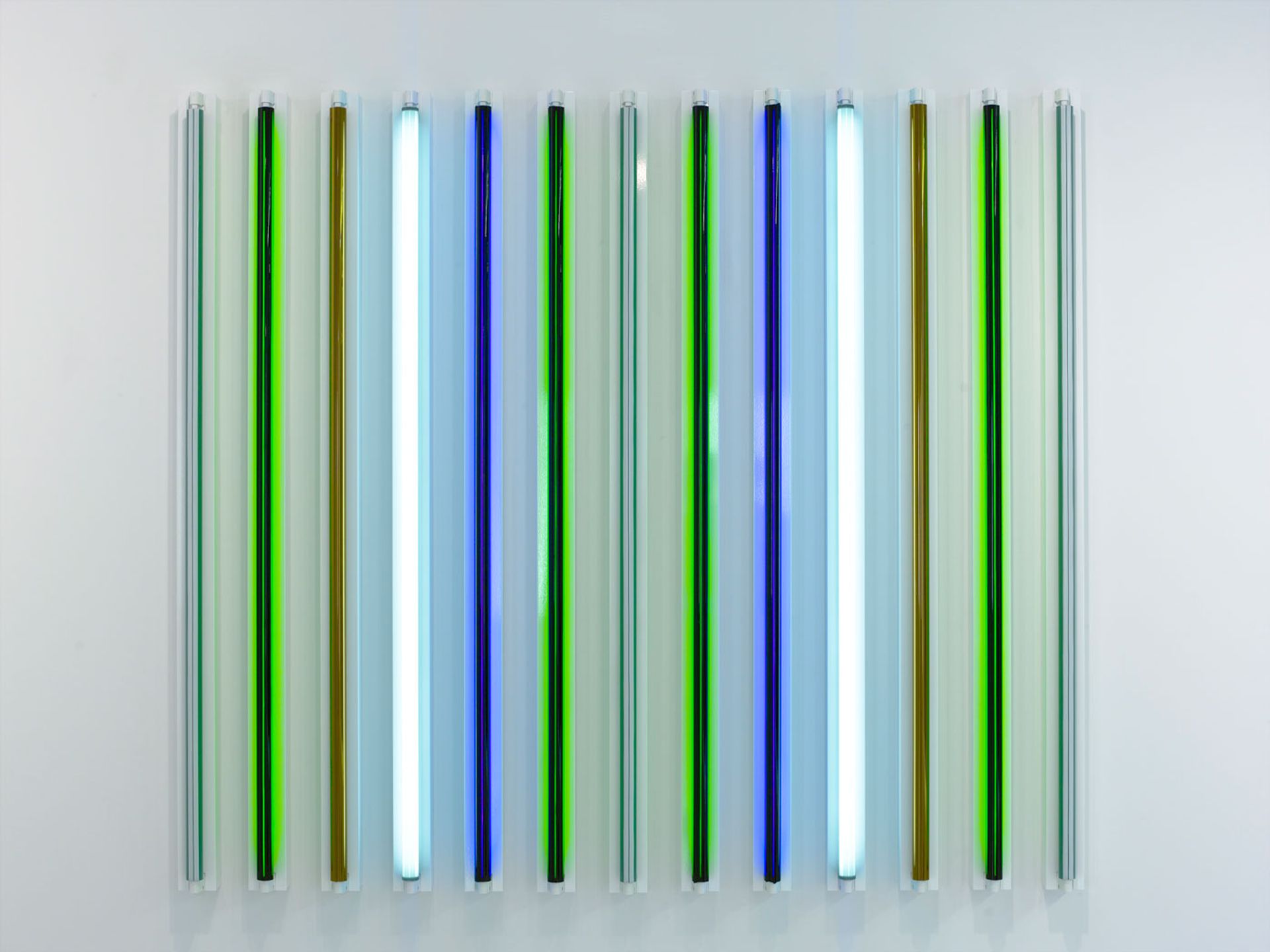

One of Irwin’s largest fluorescent works is Light and Space (2007), a permanent installation at MCASD, made up of 115 lighting tubes. Another is Niagara (2012), a corridor-length piece comprising fluorescent lamps, electrical tape, and coloured gels, at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. (In a conversation with De Salvo in 2013, Irwin said that it was a pity people often wanted to look at Niagara while standing at the centre of the work when it was much more fun to walk along its length.)

Light artists interviewed by The Art Newspaper for a recent article on light and technology almost universally cited Irwin as an important contemporary influence. To Hannes Koch, co-founder of the European collaborative studio Random International, it was “always Robert Irwin”. And that influence came not just from Irwin’s celebrated use of light, but from his study of perception—the artist‘s and the viewer‘s—and of using that experiential register to involve his audience, effortlessly and instinctively, in his works.

Robert Irwin, So. Cal, 2010 © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A son of Los Angeles

Irwin was born in Long Beach, south of Los Angeles, the son of a shipyard worker, and he served in the US military in Europe before returning to the West Coast where, from 1948, he studied at three art schools: Otis Art Institute, the Jepson and the Chouinard (now CalArts).

On a return trip to Europe in the mid 1950s, he toured museums, studying the Old Masters and—almost on a whim—took a boat to Ibiza, in the Balearic Islands, which was then still a sleepy, bohemian idyll. There, he had his first encounter with (self)-perception, spending, like some accidental Desert Father, eight months alone in an isolated cottage, conversing with no one. It was, he later said, a decisive moment in his formation as an artist. “I realised I was in the 20th century,” he later told his friend and biographer Lawrence Weschler. “And I wasn’t at all interested in historical forms.”

Robert Irwin, White Drawing, 2008-09 © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Back in Los Angeles, Irwin practised Abstract Expressionism—”big and muddy” and not very good, by his own 2013 account—and held a one-man show at the Felix Landau Gallery in 1957, while still searching for his ultimate métier. Los Angeles was affluent but conservative in the 1950s, without an established art scene, but Irwin benefited from his connection to the ground-breaking Ferus Gallery in Venice Beach, founded by Walter Hopps in 1957, which helped establish the reputations of Irwin (who joined the gallery in 1958) and other fiercely independent artists such as Robert Kienholz, Billy Al Bengston and Ed Ruscha. Writing in the New York Times in 1982, the critic Peter Schjeldahl characterised the Ferus Gallery artists’ circle of 1957-66 as “a milieu of burning ambition, provincial naïveté and leapfrogging inspiration… these artists blended impulses imported from the East with vernacular local energies: beach-blanket hedonism, car-customiser craftsmanship and Zen.”

“We banded together, looked after each other,” Irwin remembered in 2013. The Ferus Gallery brought artists like Andy Warhol, Josef Albers, Giorgio Morandi, Frank Stella and Roy Lichtenstein to the West Coast. The Morandi show, Irwin said, was one they saw as an education for Los Angeles: to see the work of a master who painted bottles repetitively “until they were no longer bottles”.

In the 1960s, Irwin made his individual mark as an artist with smaller, more focused works: first straight-line pieces, then spot paintings and his aluminium and acrylic-disc works—which stand out from the wall, creating shadows as part of the gallery display—and from the 1970s with his landmark light installations. He first exhibited with Pace in 1966, presenting his dot paintings at the gallery’s West 57th Street space in New York, and featured in some 20 further solo shows with the gallery, maintaining a close friendship with Glimcher for almost 60 years.

In 1969, Irwin engaged in another memorable phase of his experiential voyage when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) invited him to work on sensory deprivation with Turrell and the perceptual scientist Edward Wortz of the Garrett Aerospace Corporation. Turrell withdrew from the experiment before it was complete, but Irwin took copious notes on his reaction to being in ten minutes of total darkness and silence: “The trees were still trees and the street still a street, and the houses were still houses, but the world did not look the same; it had very, very noticeably altered.” As he said on another occasion: “I feel, therefore I think, therefore I am.”

Robert Irwin, untitled (dawn to dusk), 2016 © 2023 Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Alex Marks, courtesy The Chinati Foundation

The British-born dealer Peter Goulds, founding director of the Louver Gallery in Venice Beach, told The Art Newspaper in 2011 how in the 1970s, Irwin was to be found at the centre of ”the dialogue in the studios of Venice… animated, artist-led meetings with collectors and curators… held in the studios of Robert Irwin, Larry Bell and Sam Francis.”

Apart from a period spent in Las Vegas, Irwin remained in California, living and working in Los Angeles and San Diego. The opening of the Getty Museum in December 1997 was a very personal homecoming, as the complex sits just a short distance south of one of Irwin’s childhood homes in Los Angeles.

Shortly before the opening of the museum, and Irwin’s central garden, the artist told The Art Newspaper that he felt optimistic: “I find it interesting that the Getty, which is identified with and committed up to its balls in antiquities and other periods of time, is the first one that’s having a serious dialogue with me. Harold Williams [founding president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust] is the biggest populist walking around this part of the world. It’s the dead opposite of what you think it is. And if the place is well administered, it’s an incredible boon.”

Another Los Angeles work, Irwin’s Primal Palm Garden, a courtyard piece at Lacma installed between 2010 and 2016, has become a city landmark.

Irwin famously abandoned his studio practice in the 1970s, but in the past decade, while continuing to work on large site-specific pieces, he returned to the studio to develop new forms of sculpture using fluorescent light and acrylic, such as the Sculpture/Configuration pieces (2018) and his Unlight series (2020 and 2022), all shown at Pace in New York.

Irwin speaks of the sometimes-ephemeral nature of his work in a new documentary, Robert Irwin: A Desert of Pure Feeling, which has been available on streaming services since 20 October and receives its European premiere today at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. “If I say to you, ‘You can make something, and it is going to be so beautiful, the best thing you’ve ever done. Only one problem: it’s only going to last for 20 minutes…’”

Weschler published the first edition of an acclaimed biography, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin, in 1982, based on a series of longform articles for The New Yorker; and an expanded edition in 2009, the fruit of 30 years of conversations with Irwin.

Reviewing the book’s first edition in The New York Times, a typically swashbuckling Schjeldahl was struck by the mid-career Irwin’s “refusal to admit conceptual limits to the realisation of artistic perfection. Mr. Weschler reports that in the 60s, Mr. Irwin was scandalised to note that Frank Stella’s geometric paintings have sloppily uneven edges. He confronted Mr. Stella with this and was even more vexed by the answer he got: ‘It’s not important.’ Such things were so important to Mr. Irwin that his fastidiousness didn’t stop at the edges of his paintings; he would routinely replaster and repaint any wall on which a work of his was hanging… The consequences of this logical obsession with total perceptual control form the dramatic content of Mr. Weschler’s book.”

In that dramatic encounter with perceptual control, Irwin produced some of the most engrossing, thoughtful, and thought-provoking experiential art of his generation.

His work is to be found in museum collections around the world, including the Art Institute of Chicago; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC; the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid; and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Irwin’s work is at present on view at Pace’s London gallery as part of the two-artist presentation Robert Irwin and Mary Corse: Parallax.

Robert Walter Irwin, born in Long Beach, California, 12 September 1928; John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship 1984; member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters 2007; married 1956 to Nancy Olsburg (marriage dissolved), second to Adele Feinstein (one daughter); died in San Diego, California on 25 October 2023.