Hand on hip, the Black woman in Claudette Johnson’s Standing Figure with African Masks (2018) swivels round to eyeball you with a no-messing gaze. Her contrapposto pose and backdrop of flattened figures derived from Picasso’s Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907) refer back to art history, but her low-slung jeans, rucked-up shirt and challenging stare are very much in the present moment.

Nearby, another imposing Black female, nearly three metres high, clad in fashionable sports gear and cast in gold-patinated bronze, also stands with hands on hips, but her eyes are closed; she’s in an interior world of her own. Johnson’s woman is a self-portrait, whereas Thomas J. Price’s is a hybrid composite based on 3D scans of people he encountered in London and Los Angeles. But both assert a powerful, contemporary human presence while simultaneously channelling and challenging Western art traditions. And both position the Black figure centre stage, as a subject rather than an object.

Johnson’s imposing pastel and Price’s monumental bronze are among the terrific works in The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure at the National Portrait Gallery. This hugely significant show of 22 artists from the US and the UK examines and celebrates the range, richness and variety of ways in which so many Black artists from the US and the UK are currently engaging with figuration to “illuminate and celebrate the complexity and richness of Black Life”, as the curator Ekow Eshun puts it. Such an engagement marks a radical shift away from art-historical objectifications of the Black figure, and to a subjective portrayal through Black artist’s eyes—a radical reboot that packs a very particular punch within a museum founded during Britain’s Imperial heyday with a remit to amass portraits of “the most eminent persons in British history”.

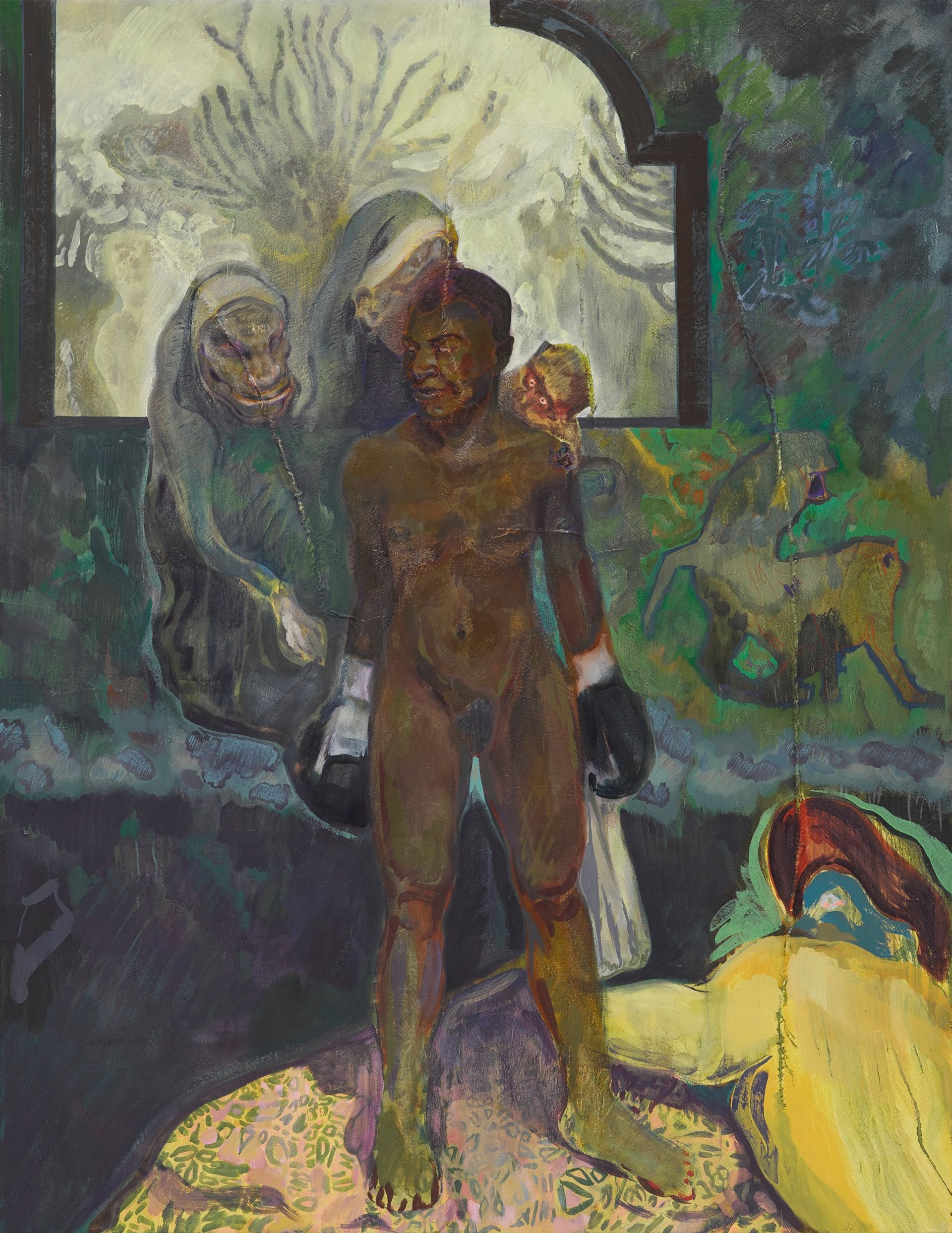

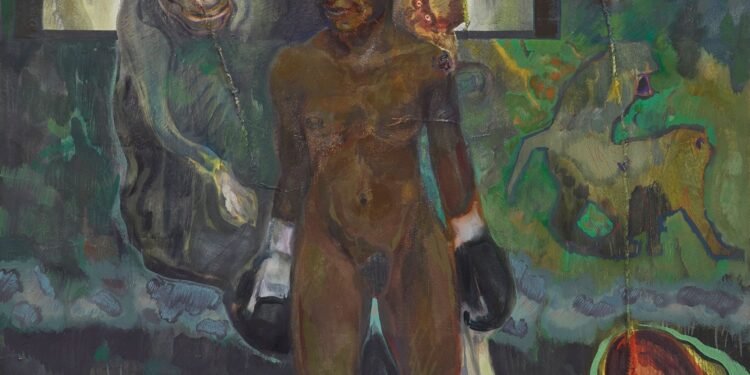

Michael Armitage’s Conjestina (2017)

Throughout, notions of visibility and representation are interrogated. In her series Vanishing Point, Barbara Walker reduces the main subjects of classic paintings to outlines embossed into thick paper, but highlights their marginalised Black bit players by meticulously drawing them in graphite, while Kimathi Donkor uses the scale and language of classic Western history paintings to depict two major female leaders from the African diaspora—Queen Nanny, head of the 1700s guerrillas, and the American abolitionist Harriet Tubman—in dramatic action. Elsewhere other grim histories are revisited, whether in Noah Davis’s coruscating rendition of the Tulsa race massacre, Lubaina Himid’s restrained retelling of atrocities committed on the notorious slave ship Le Rodeur, or Michael Armitage’s fantastical but also fraught renditions of more recent upheavals in Kenya and Uganda.

Slippery categories

Another key concept is the fundamental tension between the understanding of race as a fiction, a social construction in constant flux, but which is also navigated as a lived reality. Amy Sherald signals the slipperiness of racial categorisation by painting the skin of all her subjects in a uniform grayscale: both and neither black nor white. The jet black, uncompromisingly non-natural skin tones consistently used by Kerry James Marshall in all his figure paintings also suggest Blackness as a conceptual proposition; while in her trio of grand imagined portraits of a fictitious noble Nigerian family, Toyin Ojih Odutola presents Black flesh in dense charcoal, animated by a tracery of linear white chalk highlights, which she describes as an exploration of how her skin feels, rather than its appearance.

As its title implies, this is also a show dedicated to a multifaceted here and now, what Ekow Eshun calls “the wonder and fragility of the Black everyday”. There’s kinship and conviviality in Denzil Forrester’s tightly packed quasi-Cubist revellers at a reggae dance hall; Hurvin Anderson’s paintings of customers in the Birmingham barber shop used by him and his family; and Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s majestically scaled self-portrait holding her child in her Los Angeles garden surrounded by lush foliage rendered in a richly textured combination of paint, collage and transfers.

Jordan Casteel presents tender life-sized portrayals of an elderly couple on the streets of Harlem. Henry Taylor depicts himself hanging with his friend, the late, great Davis, who in turn painted one of the most uplifting images of the show, which captures a young boy in mid-dive into a crowded outdoor pool. It’s a wonderfully immediate expression of utter teenage exuberance, although inspired by a snapshot taken by his mother back in 1975, in the still segregated south side of Chicago. Bravo to the National Portrait Gallery for bringing together some of the most exciting artists working at the moment, who now make it impossible to view its permanent collections in the same way.

Some of the same artists are also taking part in two other complementary exhibitions which are simultaneously shaking up the canon in two of London’s other august institutions, the Royal Academy (RA) and the Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London.

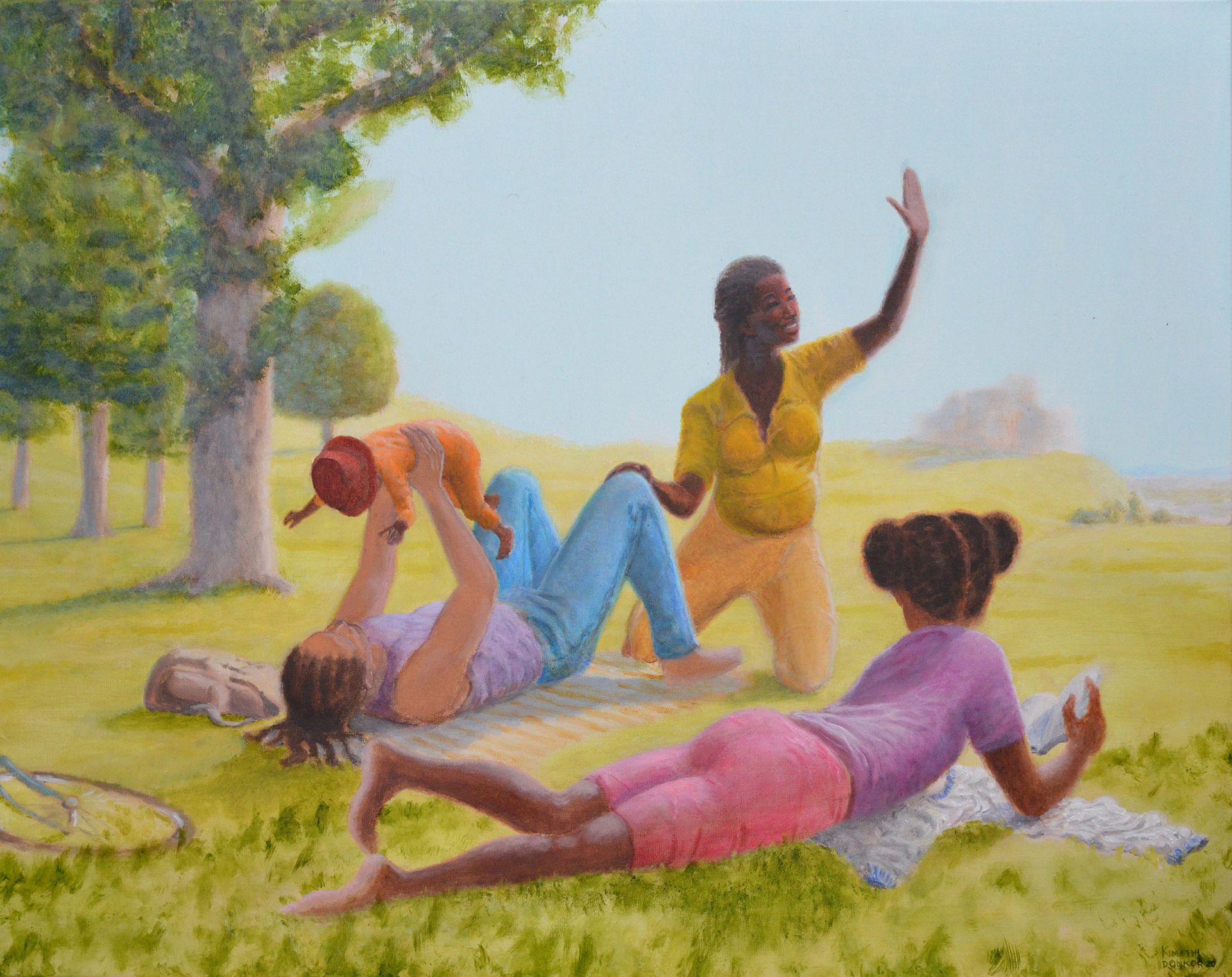

Kimathi Donkor’s On Episode Seven (2020)

Courtesy of the artist and Niru Ratnam, London. Photo: Kimathi Donkor

When it opened in in 1817, the Dulwich Picture Gallery was Britain’s first purpose-built public art gallery and it has an extensive historical collection, including works by Rembrandt, Poussin, Gainsborough, and Canaletto. In its temporary galleries its currently showing Soulscapes, in which 21 artists from the African diaspora reimagine, extend and in some cases critique the genre of landscape. Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s Cassava Garden becomes a metaphor for hybrid cultural identities, with plants built up from her dense layering of images from fashion magazines, Nigerian pop stars and samplings from family photo albums; while Kimathi Donkor now moves from epic history painting to present a series of scenic, soft focused idylls in which modern Black families can frolic at ease in sun drenched scenarios all conjured entirely out of the artist’s imagination. Bittersweet or optimistic? The viewer can decide.

In vibrant contrast to the museum’s Northern European landscapes, it’s a treat to revel in the lush but haunting tropical paintings of Ravelle Pillay, along with the rich embroidered work of Kimathi Mafafo, Alberta Whittle’s surreal circular tropical scenes and Isaac Julien’s striking riff on the sublime in his c-print of glistening turquoise Icelandic ice caves. The classic pastoral traditions enshrined in Dulwich’s collections are further challenged and complicated in Harold Offeh’s film, Body, Landscape Memory: Symphonic Variations on an African Air, in which Black figures recline and strike poses on logs and tree stumps amid leafy countryside set to a soaring musical score by the 19th-century Black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who was named after the Romantic poet. Another more trenchant critique of associations around rural Englishness can be seen in the photograph by Jermaine Francis in which a Black figure, clad in face-covering hoodie sits beside a stretch of dank and decidedly unpicturesque water bordered by scrubby trees through which some nondescript buildings are just visible.

Accompanying these interrogations of identity and entitlement embedded in the English landscape, I would like to have seen the Pastoral Interlude photographs taken by Ingrid Pollard in the 1980s of the artist and her friends in the Lake District. These were made in response to her feelings of alienation in such surroundings and her observation that, for many, “it’s as if the Black experience is only lived within an urban environment”. This is a key theme has also been taken up more recently by both Elsa James and Jade Montserrat, two other notable omissions from this show, with both artists making films in which they use their own bodies to confront and confound prejudices around a Black presence in the English landscape. This is a conversation that is by no means over and Soulscapes has opened the door for more institutions to punctuate the tainted associations around the picturesque landscape.

Tavares Strachan’s The First Supper (Galaxy Black) (2023)

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin, collection of Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. Photo by Jonty Wilde

There’s more radical rethinking at the RA which in its landmark exhibition Entangled Pasts: Art, Colonialism and Change, dives deep into its own history to unpick its profound and problematic involvement with empire, colonialism and slavery. It’s a complex and wide-ranging quest that spans from the RA’s establishment in 1768, to when it was described by its founder and first president Joshua Reynolds as an “ornament” to the British Empire, up to the present day.

Works from contemporary diaspora artists strike up bold conversations alongside historic paintings, sculptures and documents as Entangled Pasts drills into the patronage and sources of wealth that for many years underwrote the academy and its members, from painting portraits of slave owners and traders to the RA’s first treasurer being a former employee of the East India Company. It also examines the visibility and the experiences of people of colour in Georgian and Victorian Britain, as well as the widespread and ongoing cultural impact of colonialism that continues to reverberate.

The gauntlet is thrown down in the RA’S courtyard where the statue of Reynolds brandishing his easel is eclipsed by Tavares Strachan’s life sized bronze recreation of Leonardo’s Last Supper—of which the RA owns a copy—in black and gold. But in Strachan’s The First Supper (Galaxy Black), the former Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie takes the place of Christ and the Apostles are replaced by heroes of Black history, from Mary Seacole to Marcus Garvey.

There are more prominent Black figures as well as sitters whose identity is now unknown in the first room of the exhibition which is devoted to portraits of exclusively Black subjects. They include Gainsborough’s portrait of the actor and writer Ignatius Sancho, Reynolds’ painting that is probably of Frances Barber, servant and eventual heir to Samuel Johnson, and a contemporary portrait by Kerry James Marshall that pays homage to Scipio Moorhead, an enslaved artist working in Boston in the late 18th century, none of whose works survive.

This is an exhibition which crackles with exchanges between a dizzying, disturbing gathering of works spanning the centuries. Particularly effective and affecting is the room that features a swaggering Reynolds portrait of the future George IV in full state regalia and attended to by an unknown Black page; a melodramatic scene of a shark attack by the slaver-artist John Singleton Copley and Kehinde Wiley’s vivid 2024 Portrait of Kujuan Buggie, clad in contemporary streetgear whilst striking an old-masterly pose.

Installation view of Entangled Pasts; 1768–now. Art; Colonialism and Change at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (3 February – 28 April 2024), showing Hew Locke’s Armada (2017–19)

© Royal Academy of Arts; London / David Parry. © Hew Locke. All Rights Reserved; DACS 2024

All these works are hung around a central suspended flotilla of model boats from all periods by Hew Locke. Titled Armada and consisting of galleons, fishing boats and cargo ships as well as more famous vessels such as the Mayflower and HMT Empire Windrush, this spectacular fleet is a dramatic reminder of the reliance of colonialism and the slave trade on shipping and navigation. But in this complex work they are also symbols of hope with Locke also describing them as votive boats, offering survival from perils at sea and the chance of new futures.

The idea of the ocean as a site of power, trauma and loss as well as an ongoing motif for discourse around migration, extraction and environmental issues is developed in one of the show’s most powerful sections, entitled The Aquatic Sublime. Here Turner’s thundering tumultuous seascapes are brought into dialogue with both Ellen Gallagher’s richly layered paintings which meditate on the lost lives of slaves cast overboard during the Middle Passage between Africa and the Americas and Frank Bowling’s haunting painting Middle Passage, where the faint outlines of African and American continents can just be made out, embedded within its hot red and orange surface.

Another highpoint is John Akomfrah’s majestic three-screen video Vertigo Sea. Here both archival and newly shot footage are brilliantly edited into an epic, expansive meditation on humankind’s troubling relationship with the ocean, past and present, encompassing colonialism, extraction and climate and ecological catastrophe.

Installation view of Entangled Pasts; 1768–now. Art; Colonialism and Change at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (3 February – 28 April 2024), showing Lubaina Himid’s Naming the Money (2004)

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts; London / David Parry. © Lubaina Himid

There’s tragedy but also joyousness in one of the exhibition’s culminating works: the brilliant installation Naming the Money by Lubaina Himid which fills an entire two galleries with a vivacious crowd of 100 brightly painted life-sized figures. Striding, cavorting and playing a variety of instruments, they represent and memorialise the Africans who were brought to Europe as slaves or servants. Labels on their backs identify each individual, giving both their original African names and occupations as well those imposed by their new European owners. They make poignant reading: one mapmaker is identified thus: “My name is Akim/They call me Jack/I used to measure mountains/Now I measure the estate/But I have the sky.”

Surrounded by a swirling soundtrack that sets their stories to Cuban, Irish, Jewish and African music, this animated and individually identified throng speaks to all the vanished, unnamed individuals evoked in this exhibition, portrayed but so often unnamed in its artworks. Himid pays tribute to the power of human resilience, community and creativity in the face of humiliation, and loss of liberty and demonstrates the how today’s artists can face the horrors of the past and to offer new narratives. As she astutely observes, “we need to ask the questions and give the answers: creative people are the best people to give the answers…acknowledgement of what’s been hidden, what’s been erased is more important than destroying something that’s already there. We can outclass that any day”.

Of course it will take more than a trio of shows to address the grim and enduring legacies of colonialism that permeate our museums and galleries. But at least in three of London’s leading institutions the conversations can genuinely be said to have begun. Hopefully they will be impossible to stop.

• The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure , National Portrait Gallery – until 19 May; Soulscapes, Dulwich Picture Gallery – until 2 June; Entangled Pasts: 1768-Now, Art ,Colonialism and Change – Royal Academy until 28 April

![[ReBroadcast] Big Brothers Big Sisters: Serving the Community](https://lbnntv.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ReBroadcast-Big-Brothers-Big-Sisters-Serving-the-Community-120x86.jpg)