The rapidly declining number of the Tradouw or Barrydale redfin fish is raising concerns about the quantity and quality of water in the Langeberg Mountain catchment in the Western Cape.

To address this, a three-year WWF Nedbank Green Trust project launched in November 2024 aims to promote collective water resource management in the Huis-Tradouw River system. It is within the Langeberg Strategic Water Source Area (SWSA), which is one of 21 SWSAs in South Africa. These SWSAs either supply a disproportionate quantity of mean annual surface water runoff to their size and so are considered nationally important, or have high groundwater recharge and where the groundwater forms a nationally important resource.

The project aims to implement collective water resource management in the Huis-Tradouw River System to prevent further degradation of the water in the area.

Heading this project is Aileen Anderson, a water resource and business management specialist, and the general manager of a large conservancy in the area called the Grootvadersbosch Conservancy (GVBC). The conservancy has 19 members, including private landowners and farmers, and is the oldest conservancy in the Western Cape.

“The specific watershed in the region,” she explains, ‘is the Huis-Tradouw river system, which is highly contested as there are multiple users, including commercial and small-scale wheat, dairy, fruit, vegetable and vegetable seed farmers, as well as conservation areas, and the communities of Smitsville and Barrydale.”

Collective resource management

Community members during an invasive plant clean up, so far 8 km of invasive species have been cleared

“The WWF Nedbank Green Trust project aims to get all the users to share the water fairly, not only for human use but also to improve the ecological flow. In other words, maintaining the amount of water in the system to keep it flowing and healthy,” explains Poovi Pillay, executive head of corporate social impact at Nedbank.

Anderson adds, “If we look at the Huis River, for example, it has reached a state where its water resources are insufficient to meet the area’s water needs. Some estimates have shown that the river could be overallocated by more than 80% but more information is needed to verify this claim.” The effects of water scarcity are felt primarily in the drier summer months and are exacerbated by drought and climate change.

The redfin fish

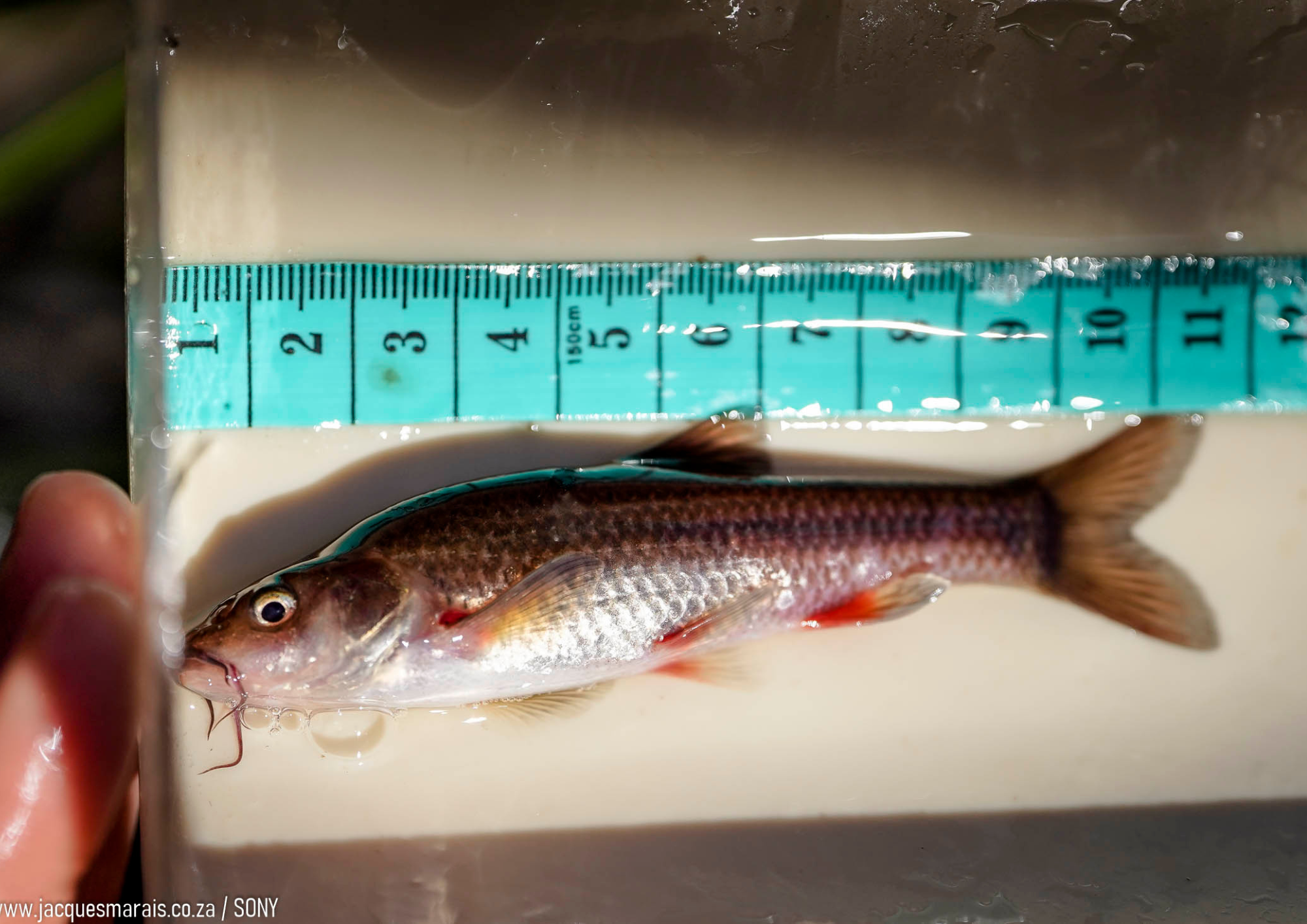

The critically endangered refin fish, raising a red flag over water quantity and quality

The Huis River is the last refuge for an isolated population of critically endangered Tradouw or Barrydale redfin that survives in isolated pools near Barrydale and in the Tradouw Pass.

“The redfin is our flagship species, and the key to its survival is to keep the base flow of the water constant so that there is interconnectedness between all the different pools, which also maintains the ecological flow throughout the Huis-Tradouw System,” says Anderson. Partners supporting the redfin project are the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the International Climate Initiative, CapeNature, the Gouritz Cluster Biosphere Reserve, and the Species Survival Commission

Anderson explains that there is no way to improve the system management until the exact amount of water coming in, through rain and runoff, and out, through municipal diversion, domestic irrigation, and agricultural use, is quantified. She also says that this must be measured against how much of the system can be used while maintaining its own ecological flow.

With the WWF Nedbank Green Trust project funding, they have started putting in monitoring systems, led by three specialists in partnership with the Swellendam Municipality. These are a water engineer Frankie A’Bear, aquatic ecologist Bruce Paxton from the Freshwater Research Centre (FRC) and hydrologist Gerald Howard, in partnership with the Swellendam Municipality

They have decided on the best locations for the monitoring equipment and have installed the loggers. “Once we have enough information, we will work closely with all stakeholders involved to help them manage the system for the benefit of the users and the environment,’ Anderson explains.

Other conservation efforts

Part of the conservation efforts includes

getting the community involved in planting

native species after alien species removal

To increase water flow, the conservancy has also been involved in invasive clearing and restoration in the broader catchment for 11 years, with periodic funding from the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment; the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development; and landowners. To date, eight km have been cleared in the Huis and Tradouw catchments.

They have also released biological control of hakea species in the mountains around Barrydale. This is a fungus that naturally controls the species. There are several alien invasive species in this area, including eucalyptus, black wattle and sesbania, hakea and pine.

“An important part of this initiative is the creation of green jobs in alien clearing and indigenous vegetation restoration to stabilise the riverine areas and re-establish wetlands,” says Anderson, who continues, “Through our local contractor teams, we employ over 120 people a year, and this is now expanding on the Barrydale side.”

Part of the work is addressed at natural solutions to help improve the functioning of the wastewater treatment works outside Barrydale, which discharges into a tributary of the Tradouw River.

Part of this work is looking to natural solutions that improve the functionality of the wastewater treatment works outside of Barrydale, which discharges into the tributary of the Tradouw River.

“Its current undersized capacity makes it a point source of pollution for the system,” says Anderson.

“We are helping the municipality to restore a sizeable wetland there to polish the water before it flows into the river.’ This restoration process includes propagating wetland species that are suited to this environment. While the wastewater treatment works are scheduled for an upgrade, the polishing wetland will provide an additional buffer to improve water quality and protect the river during and after the upgrade.

“Over the years, we have developed a positive working relationship with the farmers and community members from Barrydale and Smitsville, who are all concerned about the water supply and the implications for their lives and livelihoods,” explains Anderson.

“Everyone can play their part along the whole catchment to collectively manage the shared water resource.”

She says their willingness is evident, but they require technical assistance and support to achieve this. The project aims to be a catalyst for this collective effort by empowering local stakeholders with the tools and knowledge needed to better understand and more effectively manage their water resources