With the proliferation of states that have abolished the rule against perpetuities (RAP) or introduced a statutory RAP with an extremely long term (for example, 800 years or 1,000 years), settlors may be inclined to impose restrictions on distributions with the goal of preserving trust principal for several future generations. We’ll explore and question the logic of this strategy.

Genetic Connections

Genetic connections decrease with each future generation. As life expectancies increase, more and more individuals have the opportunity to know their grandchildren and watch them grow up. Still, only a small percentage of people are alive to know their great-grandchildren. From a genetic perspective, the percentage of DNA shared by a grandparent and grandchild is approximately 25%, which percentage is halved for each succeeding generation.1 The percentage of shared DNA decreases to less than 1% after seven generations.2 Getting to a seventh generation occurs much faster than people realize: Assuming each generation has children at age 30,

a settlor who dies at age 90 would have a fifth-generation descendant born 60 years after their death, and a seventh-generation descendant would be born 120 years after their death.3 Reaching the seventh generation doesn’t take seven lifetimes because generations overlap (a generation begins before the prior ones die). Once you reach another seven generations, that is, the 14th generation of a settlor’s descendants, the percentage of shared DNA with the settlor (0.0061%) is roughly the same as with any randomly selected stranger.4 Yet, many settlors may choose to restrict distributions of trust principal to their children and grandchildren (the descendants they know and love) to preserve assets for future, more remote descendants. Does this make sense?

Duration of RAP Trust

Under the common law RAP, a trust must end 21 years after the death of the survivor of designated persons or a class of persons (for example, the descendants of the settlor) living at the date of the creation of the trust or, in the case of a trust created under a revocable trust agreement, the date on which the trust becomes irrevocable. If a settlor uses their descendants as the class of measuring lives, this means that: (1) a trust created (or a trust that becomes irrevocable) while a grandchild but no great-grandchild is living must end 21 years after the grandchild’s death; and (2) a trust created (or a trust that becomes irrevocable) while a great-grandchild is living must end 21 years after the great-grandchild’s death.

Let’s assume everyone has children at age 30 and lives to age 90. A settlor who dies at age 90 would have a 60-year-old child and a 30-year-old grandchild. A testamentary trust would end 21 years after the grandchild’s death, meaning the trust will last 81 years (the grandchild’s remaining 60 years of life plus 21 years). At that termination, based on our assumptions, great-great-great-grandchildren would be living—five generations below the settlor. If the settlor also had a one-year-old great-grandchild at death, then the trust would last 110 years (the great-grandchild’s remaining 89 years of life plus 21 years). The range of RAP periods is 81 to 110 years in these scenarios, when fifth- and sixth-generation descendants are likely to be alive. The trustee could be given flexibility to distribute the trust property among the multiple living generations when the trust terminates.

The RAP period is calculated similarly for irrevocable trusts funded during the settlor’s life. If the settlor creates an irrevocable trust at age 50 when a 20-year-old child is living, the trust will last 91 years (the child’s remaining 70 years of life plus 21 years). If the irrevocable trust is instead created when the settlor is age 70 and has a 10-year-old grandchild, the trust would last 101 years (the grandchild’s remaining 80 years of life plus 21 years).

In most cases, a common law RAP trust will serve to adequately provide for all those descendants whom the settlor would wish to benefit and who share more than an insignificant amount of DNA. But if the settlor dies young, when only a 10-year-old child is living, the trust will end 21 years after the child’s death. If the child lives to 90, then the trust will last 101 years (the child’s remaining 80 years of life plus 21 years), but if the child also dies young, then the trust will end much sooner. So, to eliminate the risk of shortening the RAP due to early deaths, in particular when the settlor has a small family, it’s advisable to choose the descendants of a prolific individual with a large family as the class of measuring lives, for example, the descendants of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. (the father of John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States). With a descendant born every few years, this would give the trustee the longest runway to make distributions in a thoughtful manner among multiple generations. Also, with many individuals included in the class of measuring lives, one person dying young won’t have a big impact on the RAP period.

Amount Received

As noted above, settlors may choose to restrict distributions of trust principal to their children and grandchildren to preserve assets for future, more remote descendants. Restricting distributions to income or a small percentage of principal means that the overwhelming majority of the trust property won’t be available to the settlor’s children and grandchildren (the descendants with whom the settlor had the closest relationships) and ultimately distributed in a lump sum distribution to more remote descendants, whom the settlor likely never met.

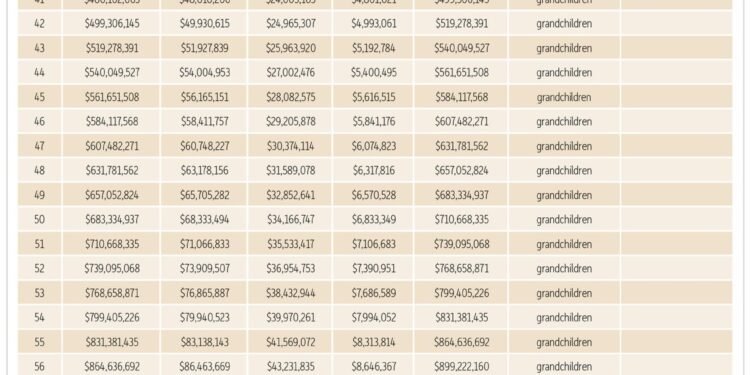

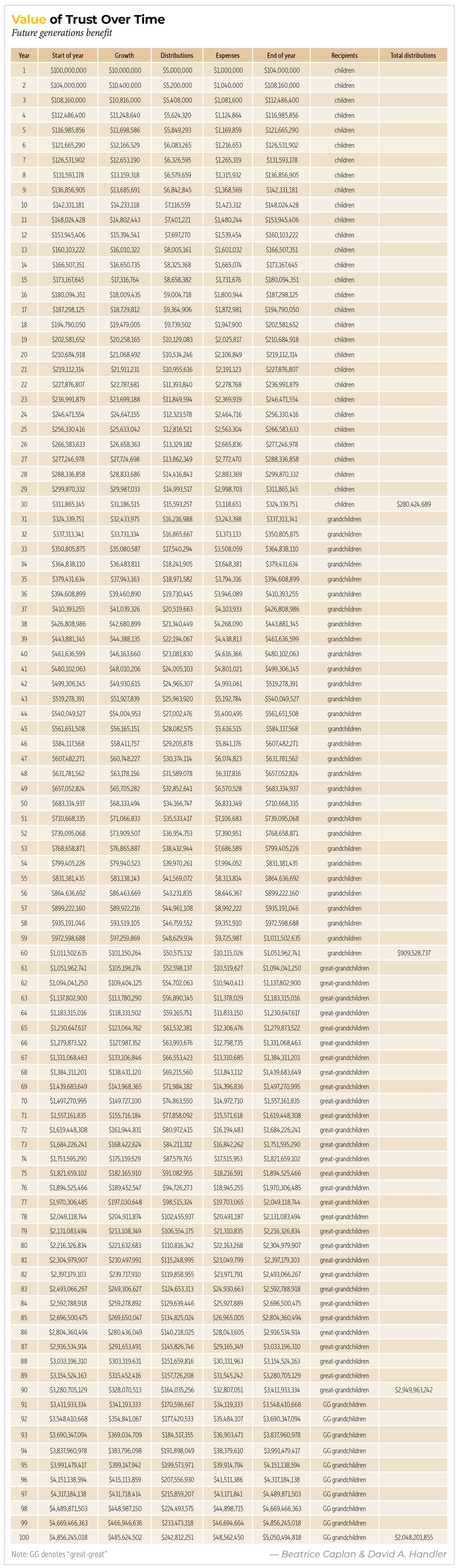

Let’s look at an example. Assume a trust is funded with $100 million at the settlor’s death at age 90, the trust fund grows 10% per year, 1% of the trust fund is used for expenses each year and annual distributions are limited to 5% of the trust fund, that is, net of distributions and expenses, the trust fund grows 4% per year. The value of the trust in 100 years (the approximate duration of a common law RAP trust) will be about $5 billion. Assuming each generation survives 30 years after the preceding one, the children would have received a total of $280 million over 30 years, the grandchildren would have received $909 million over 30 years, the great-grandchildren would have received $2.9 billion over 30 years and the great-great-grandchildren would have received about $2 billion in distributions during the term of the trust and will receive the $5 billion remaining in the trust when the RAP period ends, or $7 billion total. See “Value of Trust Over Time,” below. And as noted above, the great-great-grandchildren will share about 6.25% of the settlor’s DNA. Further, assuming each individual at each generation has three children, there will be 81 great-great-grandchildren living at termination of the RAP when the trust has $5 billion remaining. This equates to approximately $61 million per great-great-grandchild, or $3 million in today’s dollars (at 3% annual inflation), which will be distributed outright to the living great-great-grandchildren, individuals whom the settlor will never have known, with nothing distributed to any afterborn great-great-grandchildren. Is this really what the settlor would have wanted, or would their objectives have been better served if their children and grandchildren, the descendants whom they knew and loved, were able to benefit from more of the trust property?

When a trust isn’t subject to any RAP or subject to a long-term statutory RAP (for example, 1,000 years), the impact of restricting trust distributions becomes even more stark. Using the same base facts as the prior example, the value of the $100 million trust in 150 years will be almost $36 billion, and there will be 729 great-great-great-great-grandchildren living. That’s almost $50 million each, which is $593,000 in today’s dollars, for individuals who are six generations removed from the settlor and share only 1.5% of the settlor’s DNA. This seems an absurd result. Instead, the settlor should prioritize distributions to those descendants whom the settlor knew and loved during life.

The Future is Unknown

How’s a settlor to know what property, currency and tax and trust laws will look like in 100 years, let alone beyond that? A trust set up in 1875 would be 150 years old today. A trust that’s 250 years old today would have been created before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The one certainty is that the world changes drastically and unpredictably during any 100-year period and more so over longer periods. By restricting the trust distributions, settlors are tying up the principal to be disposed of in an unknown world to persons unknown to them. For example, under current law, trusts that are exempt from generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax can last indefinitely. However, there have been numerous proposals in recent years to restrict the duration of GST-exempt trusts to 90 years. There’s a trend generally towards providing flexibility in trust agreements to address future circumstances, so it makes logical sense to provide similar flexibility with respect to distributions and not tie up the principal for distribution under unknown, potentially unfavorable circumstances.

Furthermore, the longer a trust has been in existence, the greater the number of beneficiaries and the less the connection among them. Here’s an example that may be surprising: If Samuel Hinckley created a perpetual trust for his descendants on his death in 1662, both former President Barack Obama and former President George W. Bush would be beneficiaries of that trust today.5 And that’s after less than 400 years of the trust’s existence. Imagine how broad the beneficiary class would be after 1,000 years.

Optimizing Trusts

Aside from preserving assets for subsequent generations, settlors frequently limit trust distributions to their children and grandchildren so as not to curtail their ambition and work ethic. However, this objective can be achieved without locking up the trust principal for decades. A settlor can simply limit the amount funded to the trust in the first place or give a third-party trustee broad discretion to refrain from making distributions. A settlor may then wish to consider making larger gifts and/or bequests to charity or to other family members, for example, nieces and nephews and/or their children, whom the settlor knew during their lifetime and with whom they share a closer genetic connection. There’s a DNA overlap of approximately 25% between an uncle/aunt and a niece/nephew and of approximately 12.5% between a great uncle/aunt and a great niece/nephew, compared to an overlap of approximately 6.5% between a great-great-grandparent and a great-great-grandchild.6

A settlor’s desire to benefit their children and grandchildren will include enabling them to provide for their own children and grandchildren. However, this objective can also be achieved without restricting distributions to the settlor’s most immediate descendants. Instead, a trust can provide the trustee with broad discretion to make distributions among the generations, thereby enabling future generations to benefit from the trust without hampering the ability of the settlor’s closest descendants to do so. In addition, the trustee’s distribution authority shouldn’t be limited to distributions to the most senior living generation, but rather the trustee should have the ability to make distributions at any generational level. This will enable distributions to be made to lower generations in anticipation of the termination of the RAP period, the date of which will be known 21 years in advance, that is, on the death of the last surviving member of the class of measuring lives.

Private Foundations

The issue we’ve addressed applies equally to private foundations (PFs). The creator of a PF may choose to limit the charitable distributions that may be made each year, for example, a maximum of 5% of the value of the foundation’s assets, with the goal of the foundation existing in perpetuity. However, the result of such a direction is that the future distribution of the PF’s assets will be under the control of individuals whom the creator never knew, and the deployment of much needed funds for worthwhile charitable causes will be greatly deferred.

Rethinking Trust Structure

It’s easy to understand why the idea of creating a vehicle that endures for generations may initially appeal to clients. However, we encourage estate-planners to explore with their clients whether limiting the benefits provided to the client’s descendants, whom they’ve known and loved during their lifetimes, to preserve assets for future unknown descendants is, in fact, their desired outcome, after considering the points we’ve raised.

As described above, the fifth generation of a settlor’s descendants (who share about 3.125% of the settlor’s DNA) will arrive about 60 years after the settlor’s death. The seventh generation (who share less than 1% of the settlor’s DNA) will be born just over 100 years after the settlor’s death—not hundreds of years later, as is often assumed. A common law RAP trust will, in most cases, last until the sixth or seventh generation of the settlor’s descendants and, with sufficiently broad distribution authority, enable all such generations to benefit from the trust. That is, a settlor doesn’t need to resort to a perpetual trust or impose significant restrictions on distributions to their children and grandchildren for the trust to reach all those descendants with whom they share more than a trivial amount of DNA.

Endnotes

1. See Lawrence W. Waggoner, “From Here to Eternity: The Folly of Perpetual Trusts,” Univ. of Mich. Pub. L. & Legal Theory Research Paper (Updated July 2016).

2. Ibid.

3. If each generation has children at age 28, a seventh-generation descendant would be born 106 years after death.

4. Supra note 1.

5. Samuel Hinckley is the 10x great-grandfather of both such former presidents. Supra note 1.

6. Supra note 1.