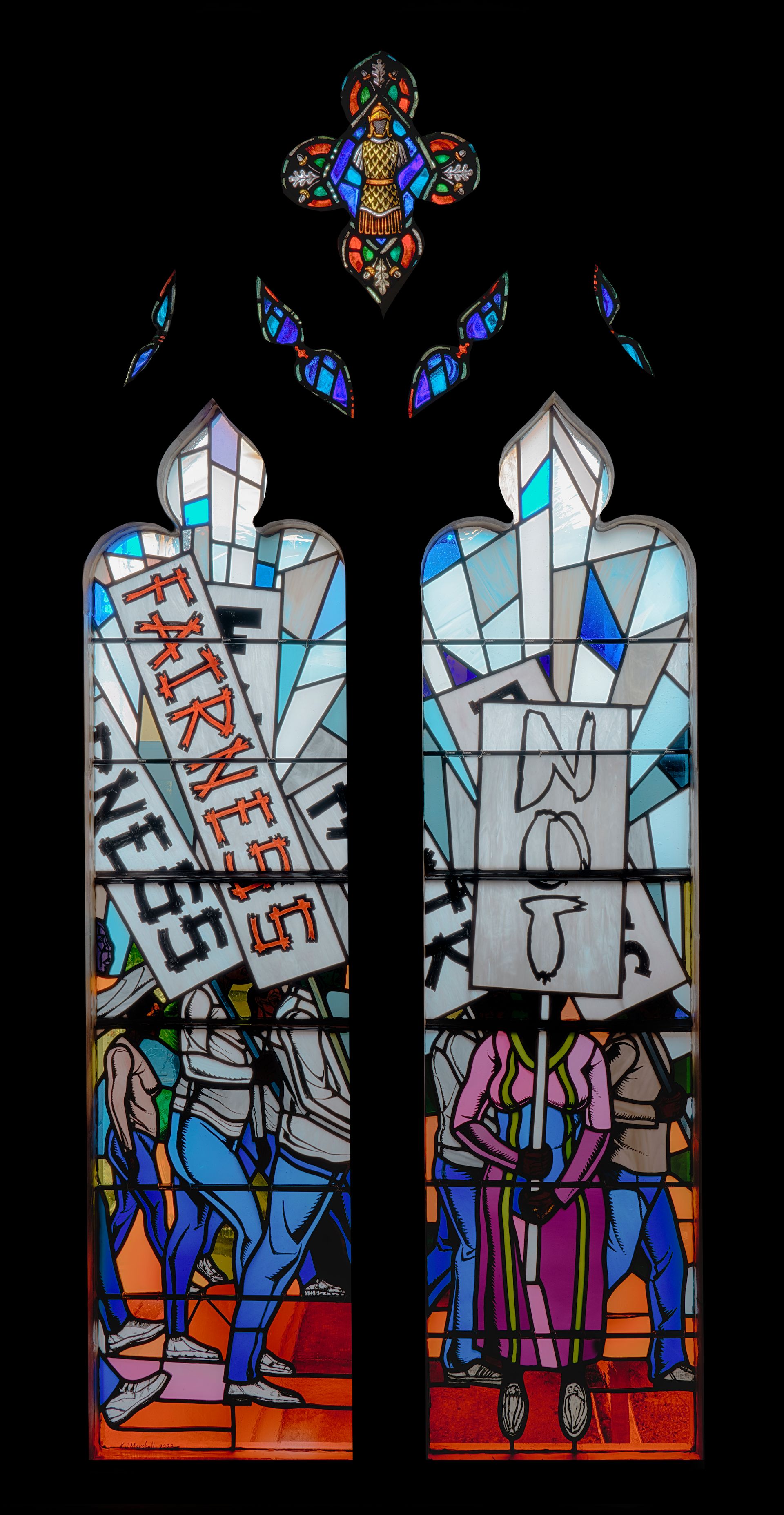

Six years after it removed two contentious stained-glass windows honouring the Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, DC, has unveiled their replacements: a set of new panes designed by the artist Kerry James Marshall that aim to tell a more inclusive history of the United States. The windows, titled Now and Forever, were dedicated over the weekend, marking what Marshall described in a statement as “a change of symbolism” that is intended “to repair a breach of America’s creation promise of liberty and justice for all”.

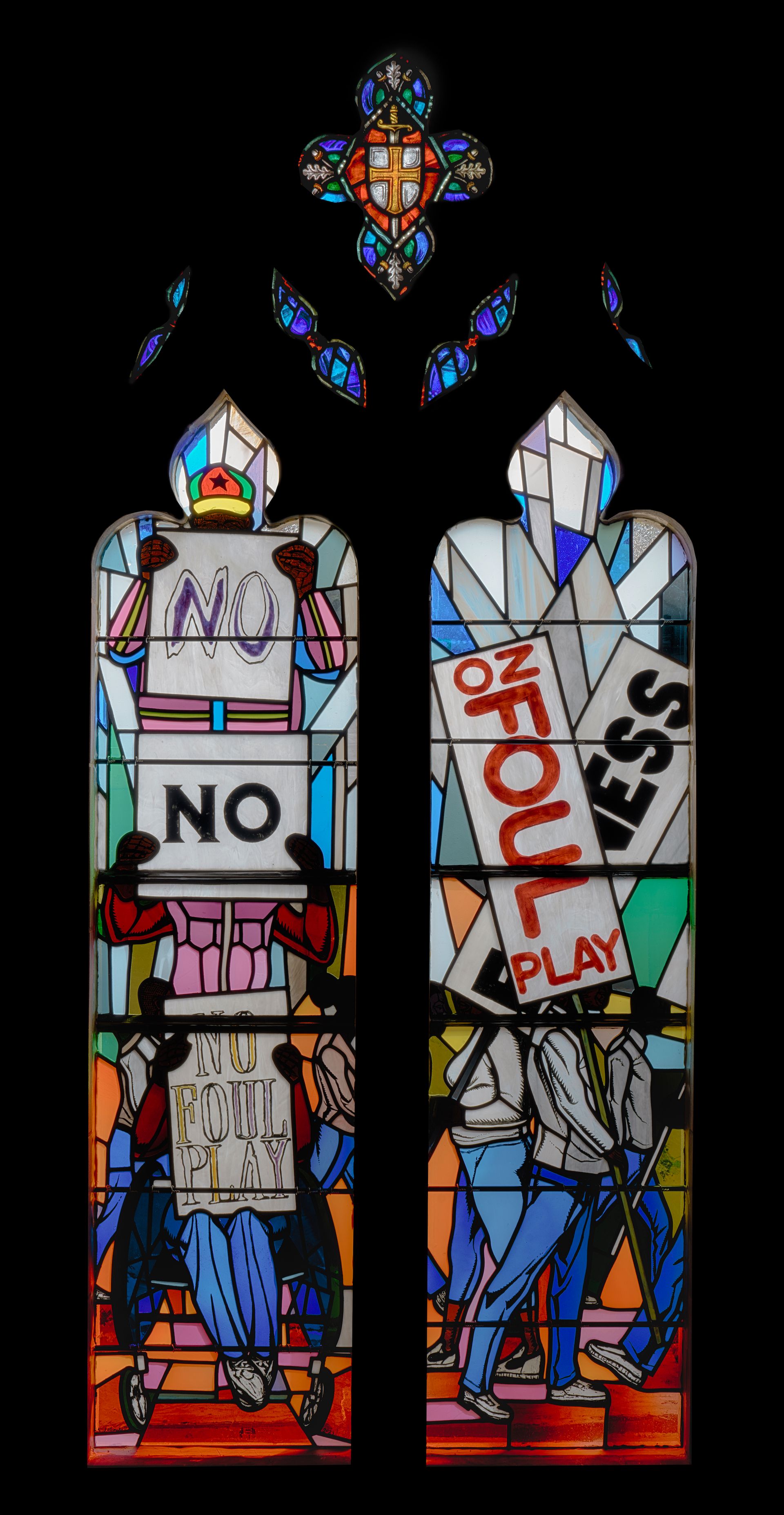

Installed in two adjacent bays, the new windows depict a crowd of Black demonstrators holding signs with messages that read “No foul play”, Fairness”, “Not” and “No”. The scene is intended to portray the ongoing march towards justice and equality, rather than a commemoration of a particular historical moment, while acknowledging the enduring efforts of Black people in the nationwide fight for civil rights.

Kerry James Marshall, detail of Now and Forever (2023) Photo: Courtesy the Washington National Cathedral

“[Pieces of art] can invite us and anybody who sees them to reflect on the propositions they present, and to imagine oneself as a subject and an author of a never-ending story that has yet to be told,” Marshall said. “This is what I tried to do, with words, images and coloured glass, for right here and right now.”

The installation of Now and Forever comes 70 years after the dedication of the original windows to Lee and Jackson in 1953. Donated by the group United Daughters of the Confederacy, they were designed by the Boston artist Wilbur H. Burnham and portray the men as Christian crusaders alongside images of the Confederate battle flag.

In 2015, following the murder of nine Black members of Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, by a white-supremacist gunman, the National Cathedral’s then dean, Gary Hall, called for the windows to be removed. In a public statement, he argued that celebrating the lives of Lee and Jackson—both enslavers—did not promote “healing and reconciliation”, as previous cathedral leadership had hoped.

Kerry James Marshall, detail of Now and Forever (2023) Photo: Courtesy the Washington National Cathedral

A task force was formed to decide how to handle the windows’ future, and in 2016, the cathedral removed the images of the Confederate battle flags. The rest of the windows came down the following year, after white supremacists protested the removal of a statue of Lee, in Charlottesville, Virginia, in a violent rally that turned deadly.

“Simply put, these windows were offensive, and they were a barrier to the ministry of this cathedral, and they were antithetical to our call to be a house of prayer for all people,” Randolph Marshall Hollerith, the cathedral’s current dean, said during the dedication on Saturday. “They told a false narrative, extolling two individuals who fought to keep the institution of slavery alive in this country. They were intended to elevate the Confederacy, and they completely ignored the millions of Black Americans who have fought so hard and struggled so long to claim their birthright as equal citizens.”

In 2021, a committee unanimously selected Marshall to design new windows for the cathedral, which were fabricated by the stained-glass artisan Andrew Goldkuhle—his father, Dieter Goldkuhle, created more than 60 windows at the cathedral. Marshall, who had not previously worked with stained glass, hand-painted details on the works. Support for the project came from the Ford Foundation and the Mellon Foundation, as part of the latter’s Monuments Project, an initiative to think more critically about memorialisation and the US’s civic landscape.

Kerry James Marshall Photo: Courtesy the Washington National Cathedral

The original windows are being stored and conserved at the cathedral while officials make their final decisions about their fate. Some of the original glass, however, has been kept in situ above Marshall’s windows, as a way to remember the past. Over the next nine months, an additional work will take shape beneath: Elizabeth Alexander’s poem American Song, written for the project, will be hand-engraved onto stone tablets in the bay. The cathedral is continuing to review the iconography of all of its windows to examine existing stories within its walls and account for those that have not yet been told.

“I want to be clear that this is not the end of the end of the cathedral’s journey; rather, today is an opportunity to recommit ourselves, and to recommit this cathedral, to join that march towards fairness for all Americans, but especially for African Americans,” Hollerith said on Saturday. “There is a lot of work yet to be done to confront systemic racism, to foster racial reconciliation and to be repairers of the breach, both in the past, the present and in our future.”