Avni Pattani recalls the moment, in 2020, when she found masses of papers piled inside a house once owned by a family member in Bhavnagar in Gujarat, on the northwestern coast of India. “Over the past three years, there have been constant discoveries. I thought we were starting with a single old cupboard, but there were bundles of documents,” she says.

And hers isn’t just any family. In the colonial era, Bhavnagar was one of the so-called princely states, which retained their royal rulers. Avni’s great great grandfather was Sir Prabhashankar Pattani, the diwan, or prime minister, of the state—taking up the role in 1903 and serving in several state positions until his death in 1938. An astute administrator, he worked with the British, yet was also a friend Mahatma Gandhi. His sons, Anantrai Pattani and Batukrai Pattani, became diwan in their turn, steering Bhavnagar through as it was absorbed into India following independence in 1947.

A member of staff works their way through the archive

Courtesy of Pattani Archives

The materials Avni discovered across various family locations have, in the years since, grown to form Pattani Archives, which will open to the public in the city of Bhavnagar on 16 December.

Naturally the documents exhibited within this new space deal with political and administrative history, but, as Avni reveals, they contained much more too. “When we started to open these bundles, which had Bhavnagar Durbar [parliament] stamped on them, we realised that it wasn’t just papers, but was also maps, photographs, artworks, sketches,” she says.

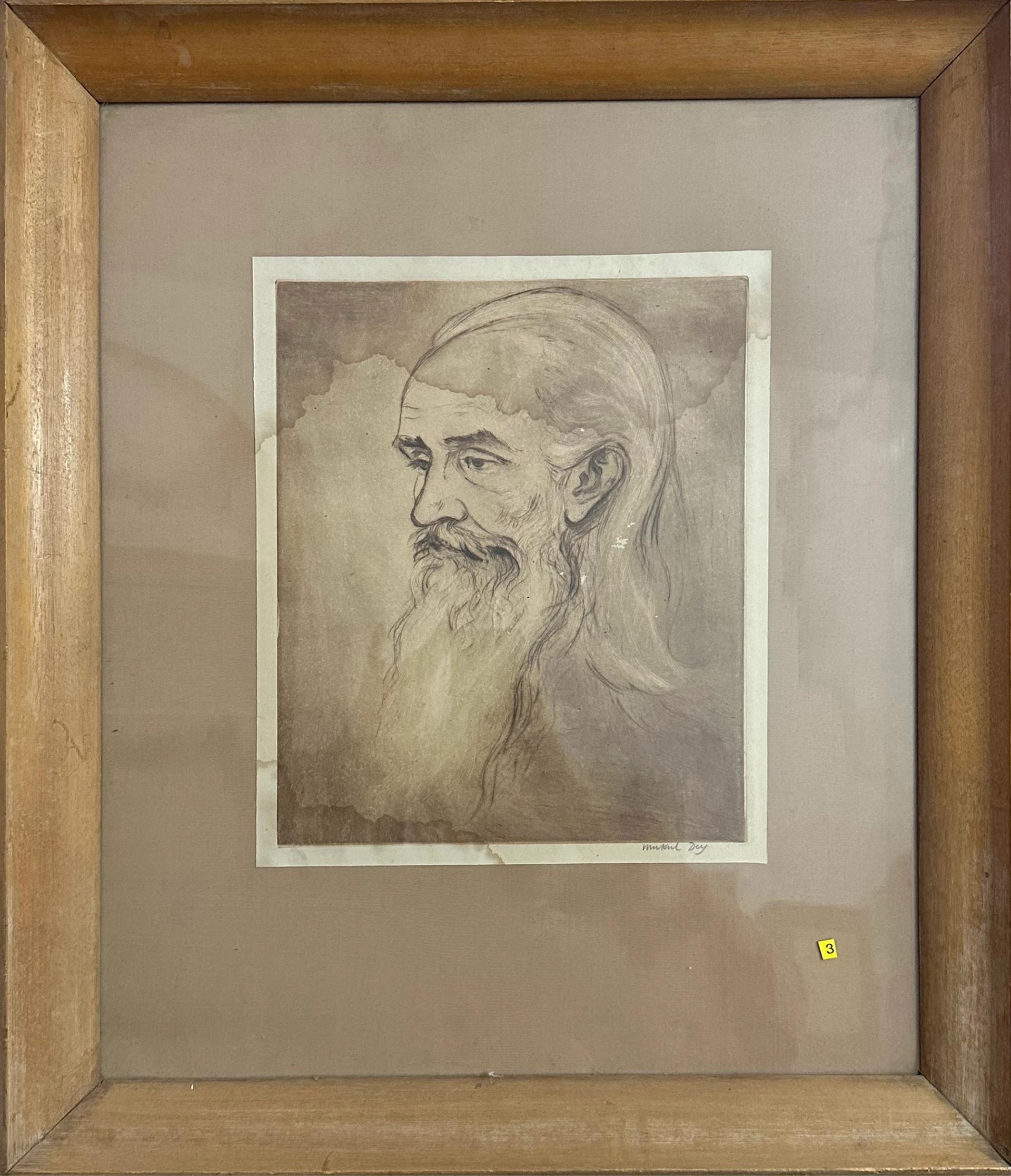

The team discovered a sketched portrait of Prabhashankar by Mukul Dey, who trained at the Slade School and the Royal College of Art in the 1920s. Having acted as a patron, correspondence reveals that Prabhashankar Pattani declined an offer of receiving gifts of works of art as he felt he was simply doing his duty.

The sketched portrait of Prabhashankar Pattani by Mukul Dey

Courtesy of Pattani Archives

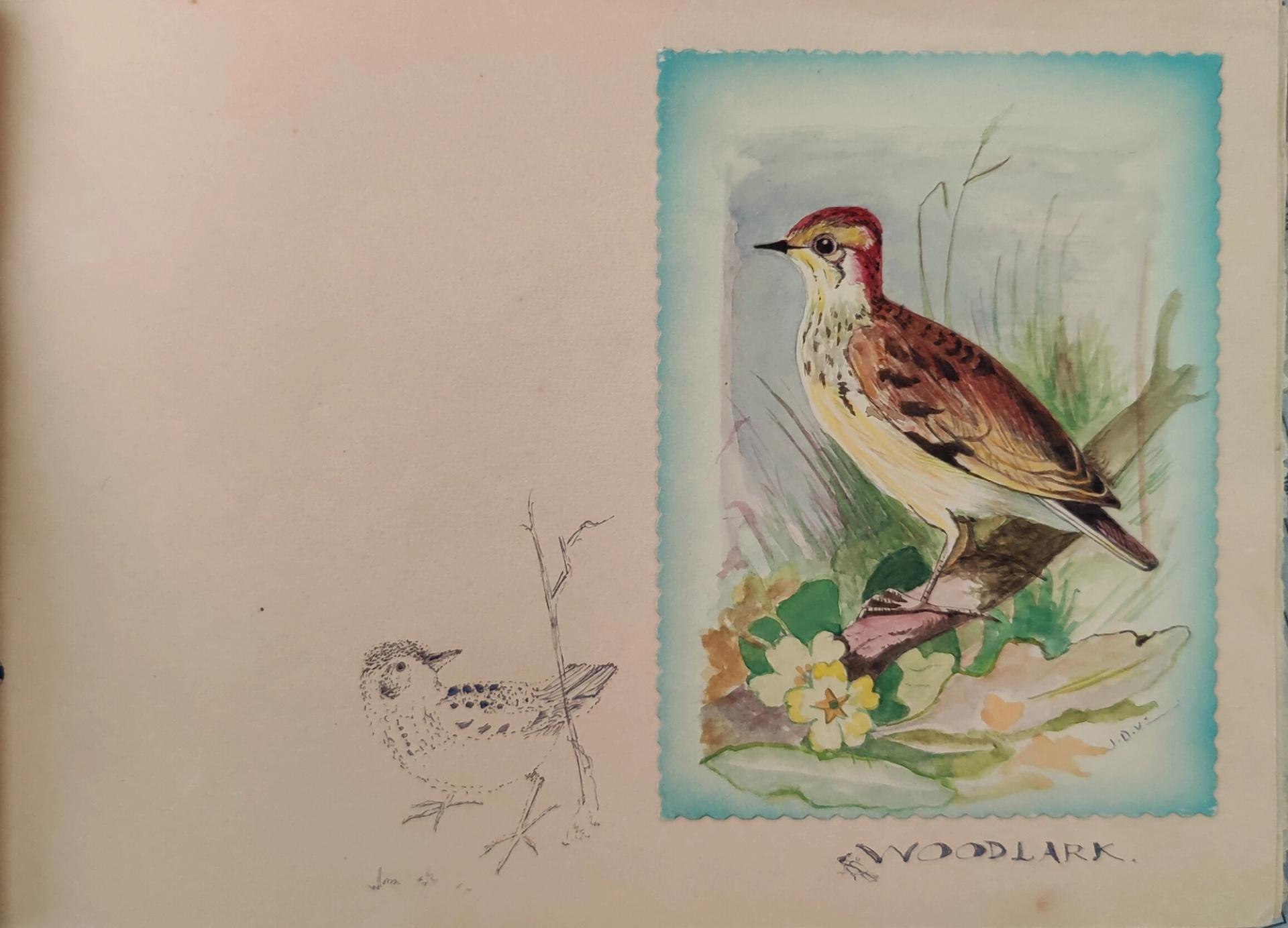

Among prints of European paintings and photographic portraits were works by local artists and artisans. Ishita Shah, consulting archivist on the project, explains: “The family had an appreciation for traditional arts from both India and Gujarat [specifically]. For instance, we found a portfolio of bird paintings by Jagdip Virani, a local electrical engineer who later trained as an art teacher. These are joined by examples of traditional furniture in the form of beautiful sandalwood writing chests, known as peti, and printing blocks used for invitation cards, showing an adaptation of a traditional technique.”

An example from a portfolio of bird paintings by Jagdip Virani, an electrical engineer who later trained as an art teacher, that was discovered by researchers working on the archive

Courtesy of Pattani Archives

Avni founded Pattani Archives so this fragile resource could be preserved and shared. The project is run under the auspices of Sir Prabhashankar Pattani Open Window Charitable Trust, established by Avni’s grandfather, Shashikant Pattani, in 1993, with further funding from individual donors. Initially working with Tana Trivedi, an academic at Ahmedabad University, Avni quickly employed a professional conservator to help them ensure that none of the material was damaged. The archive now has a dedicated building and a team of 13 staff and consultants.

The archive was founded so its fragile materials could be shared with the public

Courtesy of Pattani Archives

In addition to conserving existing documents, they have gathered materials and recorded memories from other family members and the community. Ishita, an oral historian by training, explains the significance of this initiative: “There is a strong need for archival collections, particularly in South Asia or India, to be supplemented with the voices and stories that surround the documents, even more so in this case as we are talking about four generations ago.” The oral history has enabled connections between disparate elements of the physical archive and added the voices of those, such as women, who are often excluded.

The inaugural exhibition, which will run until January 2024, consists of a series of rooms presenting some of the objects and stories found within the archive. Avni and her team have plans for future exhibitions, together with projects to develop archival skills, programmes for fellowships and postdoctoral studies, and, of course, plans to gather more documentary and oral histories. This exhibition is not the culmination of this project, but just the start.