The long-awaited trial between Dmitry Rybolovlev, the billionaire Russian collector, and Sotheby’s began yesterday (8 January) in a Manhattan district courtroom. The proceedings mark the next phase of Rybolovlev’s decade-long legal campaign to recover hundreds of millions of dollars from more than $2bn worth of acquisitions he made through the Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier.

The current trial stems from a 2018 civil lawsuit alleging the auction house “materially assisted the largest art fraud in history”, with Rybolovlev purportedly overpaying by more than $1bn for 38 works acquired via Bouvier from 2003 to 2014. The complaint’s central accusation is that Sotheby’s “aided and abetted” Bouvier in this process by supplying him with appraisals and other information used to inflate the sale prices in multiple deals.

The plaintiffs, Accent Delight International Ltd and Xitrans Finance Ltd, two British Virgin Islands-based companies through which the oligarch acquired works of art, originally sought damages of at least $380m plus interest accrued in the years since the transactions. But Judge Jesse M. Furman dismissed several of the lawsuit’s claims in a pretrial decision in 2023, meaning the trial will focus on just four private sales in which Sotheby’s played a role.

The four pieces in question are headlined by Christ as Salvator Mundi (around 1500), controversially attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and eventually resold at Christie’s New York for a record-setting $450.3m in November 2017. The others are René Magritte’s Le Domaine d’Arnheim (1938), Gustav Klimt’s 1907 painting Wasserschlangen II (Water Serpents) and Tête by Amedeo Modigliani.

Adding to the drama is the elusive Rybolovlev’s presence in court. He did not speak in the opening arguments, but the gentle hum of his Russian translator was a reminder his eventual testimony, expected next week, would take place in his native language.

Sotheby’s ‘golden goose’

Although testimony from Bouvier will enter the trial via deposition, he is not among the defendants in this case. Bouvier and Rybolovlev settled all of their legal disputes in all jurisdictions in December 2023. (Bouvier has denied all allegations of fraud from the outset, maintaining that he acted not as Rybolovlev’s representative but as a dealer free to set his own prices.) Nevertheless, Bouvier’s name and alleged misconduct were front and centre throughout day one in Judge Furman’s courtroom.

Daniel J. Kornstein, Rybolovlev’s lead counsel, framed the accusations using language that triggered numerous objections from the defense. He described Bouvier as both a “meal ticket” and a “golden goose laying golden eggs” for Sotheby’s, as well as labeled Samuel Valette, Bouvier’s liaison at Sotheby’s, a “greedy and overly ambitious middle manager” who used the auction house to “grease the wheels” while Bouvier “wormed his way” into Rybolovlev’s life.

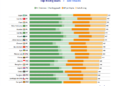

Kornstein presented financial data in court that alleged Bouvier accounted for as much as 100% of Valette’s business in 2011, resulting in his promotion. (The accusation provoked an unidentified man in the back of the courtroom to mutter, “That’s insane.”) The lawyer even defined Valette’s commissions and sales in his role as “plunder” to “substantially assist in fraud”.

Kornstein also peppered his opening statements with art metaphors, most notably accusing Sotheby’s of running a scheme “like George Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon at the Park”, in which the dots only connect when one stands back to see the whole picture.

Lack of transparency, lack of knowledge

Sotheby’s central defense is simply that the auction house had no way of knowing what Bouvier was doing behind the scenes. “If Mr. Rybolovlev has a valid gripe, it’s against Bouvier, not Sotheby’s,” said Sara Shudofsky, one of the auction house’s lawyers, on the trial’s first day.

Court filings by the auction house have consistently argued the Swiss dealer’s business was a black box to Sotheby’s, which had a “lack of any knowledge about any representations or misrepresentations Yves Bouvier made to Dmitry Rybolovlev or his affiliates”, be it lying about pricing, potentially falsifying negotiations or other potential misdeeds.

Furthermore, Rybolovlev and his lawyers face a dilemma: How can they convince a jury that Sotheby’s should be found guilty of fraud when Bouvier himself has not been?

Yet if the plaintiffs prevail, the verdict could have seismic implications for the art business. This case exemplifies how seldom either party in a high-end art market transaction fully knows who it is dealing with or in what precise capacity. Kornstein’s insistence on general mores of transparency and truth may indeed resonate with jurors, who were weeded out deliberately if they were art collectors or had any prior knowledge of the industry.

The trial is expected to last between two and seven weeks—unless Rybolovlev and Sotheby’s opt to pre-empt any such dramatic impact on the trade by settling out of court.