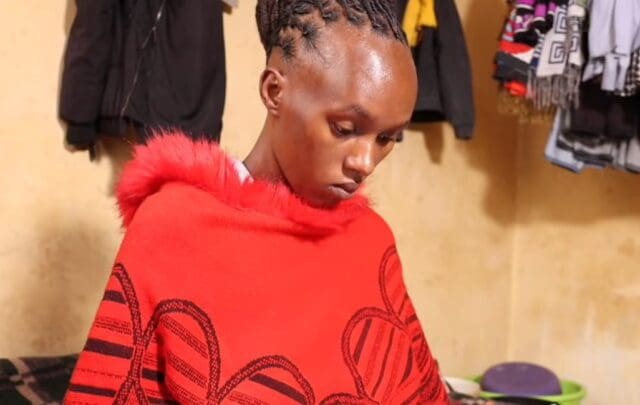

A Kenyan mother, Penina Wanjiru, is appealing for urgent government intervention after she was deported from Saudi Arabia, leaving behind her three-year-old daughter who remains in custody abroad.

Mother Seeks Reunification After Forced Deportation

Penina, 31, from Bahati in Nakuru County, travelled to Saudi Arabia in 2019 in search of employment. Her journey took a devastating turn in 2022 when she gave birth to her daughter, Precious, while living in fear of being arrested for her undocumented pregnancy.

According to Wanjiru, she hid her pregnancy throughout the term, avoiding hospitals despite medical advice that she required a caesarean section. She ultimately delivered the baby at home.

“I feared going to hospital because I risked arrest,” she said. “I delivered alone because I had no choice.”

– Advertisement –

Child Taken During Police Raid

For three years, Wanjiru quietly raised Precious with the help of a local daycare centre, attempting to keep the child away from authorities. However, the arrangement collapsed when Saudi police raided her residence.

During the operation, Precious was taken into custody, and Wanjiru was swiftly deported. She was denied any chance to gather her belongings or ensure the safety of her daughter.

“I wasn’t given time to pack,” Wanjiru said. “I told them I had a child, and they promised she would be brought to me, but that never happened. I refused to leave without her, but I was forced, beaten, and pushed out.”

DNA Test Barrier Delays Child’s Return

Since returning to Kenya nine months ago, Wanjiru has been informed that her daughter cannot be repatriated without DNA verification. This is a requirement for children born abroad out of wedlock. The process, however, has not begun, leaving Precious in limbo and at risk of being placed in an orphanage.

A Widespread Challenge for Kenyan Migrant Mothers

Wanjiru’s case highlights a growing crisis faced by many Kenyan women working in Gulf countries. They give birth under difficult or undocumented circumstances. Strict DNA verification rules have left hundreds of children without proper documentation. This prevents them from obtaining travel papers, legal identity, or repatriation.

Without recognition from either the host country or Kenyan authorities, these children often remain stranded for months or years. They live in shelters, holding facilities, or foster homes while their mothers struggle to navigate complex diplomatic and legal processes.

Appeal to Kenyan Authorities

Wanjiru says she has contacted her Member of Parliament, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Diaspora Affairs office. However, no action has been taken to initiate the DNA test or facilitate her daughter’s return.

“I just want my child back,” she said. “I am begging the government to help me bring her home.”

Human rights organizations have urged authorities to streamline DNA testing and registration procedures. This is to protect vulnerable migrant families and prevent more children from falling through bureaucratic gaps.