A digital art project designed to highlight an Icelandic fishing conglomerate’s role in an international corruption scandal will remain offline after a British judge ruled in favour of the multinational yesterday (14 November).

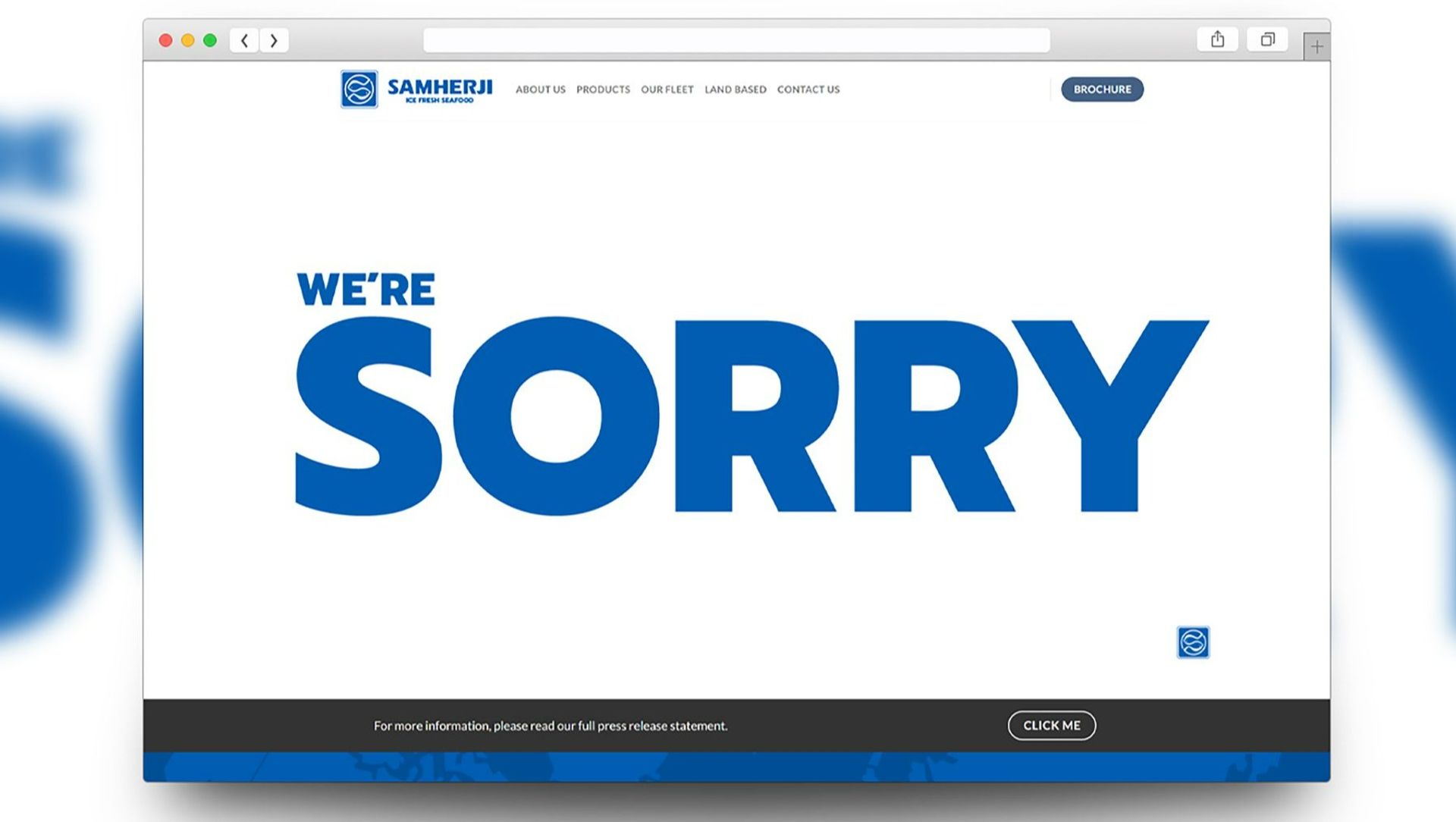

In September the Master Paul Teverson, sitting in the Intellectual Property division of London’s High Court, heard from conceptual artist Odee Fridriksson that the website he had created using the same font, colour scheme and branding as that of Samerji, one of Iceland’s largest companies, and purportedly containing an apology from the company for its role in the scandal known as Fishrot, was part of a broader artwork encompassing not only the digital component, but also an installation (of the words “We’re Sorry’ projected at the Reykjavik Museum of Art) and a social element comprising media attention on and public responses to Fishrot.

A whistleblower alleges that over several years, a number of Namibian government officials and others were bribed by Samerji in order to secure valuable fishing quotas. As a result, the tiny South African nation was defrauded of millions of dollars and marine resources were wrongfully exploited. A trial was due to start in the Namibian capital, Windhoek, in 2023 but delays—and the sudden death of the Namibian president at the start of the year—have seen proceedings postponed on at least two occasions. In the meantime, the officials remain in custody and Samerji management has denied it ordered the bribes in spite of recent reports of a trove of messages to the contrary.

Fridriksson, a student at the University of Bergen in Norway, who changed his name after the previous London hearing and is now known simply as Odee, had relied on a number of defences in court, where he represented himself with the support of the Paris-based firm Avant Garde Lawyers. In addition to his that claims that the website and “fake apology”—which included a promise from Samerji that it would work with the London-based non-governmental organisation Restitution to seek to recover the money spent on kickbacks—was a parody or pastiche, he asked that his right to free expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights be upheld.

While Master Teverson acknowledged in a 27-page judgement that the Fishrot scandal “is a current event and still under investigation”, he “did not accept that it is realistic to invoke Article 10 where a completely false and misleading press release has been put out”.

Odee had, according to the judge, “crossed the line between fair and unfair dealing”. He added: “It is clear from the design of the website that the defendant has infringed the Claimant’s copyright in the logo (…) by copying.” Regarding the installation at the museum in Reykjavik, the ruling noted that “although plainly seeking to shame the Claimant, (it) did not seek to pass itself off as an official statement or website”.

Screenshot of Odee’s (Oddur Eysteinn Friðriksson) satiric version of Samherji Group’s website, part of his project We’re Sorry (2023) Courtesy the artist

While Samerji had previously sought an injunction which resulted in the temporary removal and closure of the fake company website, the company has not yet clarified what other remedies it may seek. A date for a hearing to explore these issues is expected before Christmas, with Teverson saying he hoped that “in view of the early stage at which injected role was granted, that the costs of an inquiry could be avoided by the acceptance by the claimant of a small sum”.

Samerji sought to litigate in London because it claims the fake website damaged the goodwill it had built up via its UK business, which it operates via subsidiary companies in the UK. These businesses, Aldea and Seagold—which is now controlled by the son of the chief executive of Samerji—supply fish to a number of supermarkets and fast food outlets. Representatives for Seagold did not immediately respond to The Art Newspaper’s requests for comment.

Speaking to The Guardian, Samerji’s chief executive, Thorsteinn Már Baldvinsson, expressed satisfaction with the ruling saying: “This judgement must be a matter of serious consideration for the academic institutions that gave their blessing too obvious trademark violations under the guise of artistic expression.”

David García, professor emeritus and specialist in tactical media at the University of Bournemouth, told The Art Newspaper he disagrees “profoundly” with the judgement.

“It is a matter of what constitutes the satirical and the right to infringe traditional norms of copyright if you have satirical intent—and that’s a well-rehearsed defence,” García says. “There is precedent for this sort of thing and perhaps the best known is the work by The Yes Men, who convinced the BBC they were senior executives of the Dow Chemical Company (which bought Union Carbide, whose Indian pesticide factory caused a toxic environmental disaster killing and disabling thousands in 1984). They apologised for the death and destruction caused and committed to paying reparations and because it was the BBC everyone believed them. That was a very similar case where the artists hold companies that act with a great deal of impunity to account.”

Odee tells The Art Newspaper that he was “not altogether surprised about the result”, but was worried that it “could have a chilling effect on other artists who wish to make work that asks questions and critiques important issues”.

“The decision could be a deterrent to others as well as myself because maybe galleries would not want to get sued,” the artist says. “The purpose of this artwork was to put a spotlight on corporate responsibility and I think we can say it has served its purpose. But this ruling is not the final chapter.”