Joan Snyder, who was described in Artforum in 1986 as a “cult phenomenon”, is something of an anomaly. The US painter, now 84, gained critical acclaim early on in her career, showing in museums across the US from 1970 onwards, and has made a decent living selling her paintings. But she is still considered an outsider in the UK and Europe, and has not been represented by a blue-chip gallery—until now.

Snyder still seems unsure of why that is. “Because they didn’t like my work? Because they thought I’m a feminist?” she questions. The artist is speaking in the offices at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in London, where her exhibition, Body and Soul, opened last week (until 5 February 2025). The Austrian dealer took Snyder on in February, swiftly mounting this, her second major show in the UK; the first was in 2019 with the now defunct Blain Southern gallery.

As a woman working through the male-heavy Abstract Expressionist and Minimalist eras, Snyder considers herself one of the lucky ones, even if blue-chip gallery representation, and all the advantages that come with that, remained elusive. “I always had galleries, I always made a good living, starting from the 1970s. It wasn’t for a lack of the paintings being very sellable. They just didn’t want me,” she says. “I even knocked on some doors”— but never the likes of Gagosian or David Zwirner: “I never pursued the big four or five, they always scared me.”

Joan Snyder, First Stroke Landscape (1968) Photo: Adam Reich © Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

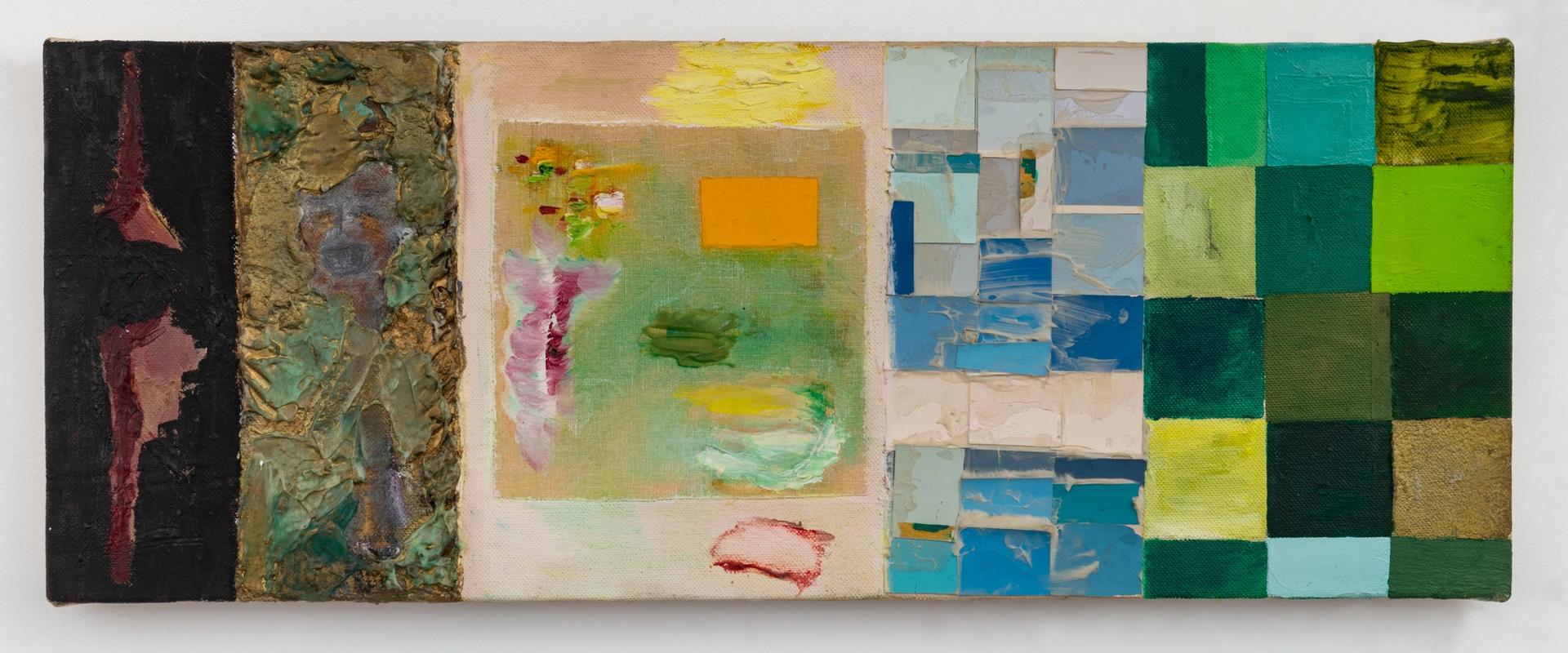

The London exhibition charts the breadth of Snyder’s 60-year-long career, which took off in the late 1960s with the development of her Stroke paintings—works consisting of brushstrokes distilled to their very essence. “The first really good painting I made, my real breakthrough was in 1969 with Lines and Strokes,” Snyder remembers. “It was crystal clear exactly what I wanted to do. It was simple, I was painting paint strokes. It was just raw canvas, primed with pencil lines and a very simple grid. Somehow it got to the heart of everything I’d been trying to do all those years.”

Those works earned Snyder a glowing reputation as well as a long line of new friends—though not all well-meaning. “There were a lot of people in my life, and I got confused about who were and who weren’t my friends,” she says. “There was huge list of people who wanted the paintings, but I had to move on.” The Stroke paintings had, Snyder says, become “too easy”.

She and her than husband, the photographer Larry Fink, bought a farm in Pennsylvania, where Snyder “isolated” herself and began to work on a new body of work that dealt with what the artist describes as “the whole concept of female sensibility”. Her paintings became expressionist, as well as autobiographical and political, incorporating materials that began to protrude from the canvas: straw, rose petals, berries, mud and fabric. “Everywhere I was seeing young women being autobiographical, using materials, sewing, just doing lots of different things that we hadn’t talked about, or we hadn’t seen,” Snyder says. “Feminism was working its way into my work in a big way, even though it was there in the mid-1960s, but it really came back.”

Joan Snyder, Baby Grand (1981) Photo: Adam Reich © Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

The personal is political became a rallying cry for feminists in the 1960s and for Snyder, the personal has always bubbled just below the surface of her canvases—in some more overtly than in others. The rose has been a recurring motif, including in some of the eight new works on show in London, but the artist is less interested in divulging any particular meaning, pointing instead to the Latin phrase “sub rosa”, meaning under the rose: in ancient times, a rose hung over a council table denoted secrecy or confidentiality. With Snyder, meaning is not easily offered up, but rather gets deliberately left behind.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Snyder had an abortion, a miscarriage and a baby (her daughter Molly) within the space of three years. “I had an abortion, then I so regretted it, then I got pregnant again immediately and I had a miscarriage after about five or six months, that was during early April,” Snyder says. For decades after, the artist made big paintings in early April about losing that baby, a baby boy to have been named Oliver.

Women’s rights—reproductive, inheritance rights, women’s struggle against abuse—are in many ways present in Snyder’s work. She shakes her head at the current political situation in the US and says quietly, “It’s a shit show.” Snyder thinks many women will be “really badly” affected by Donald Trump’s presidency: “Women being deported. Women being separated from their children and families. Women who are in crisis and might need medical help. Women who are raped and have to go through a pregnancy.”

Body & Soul (1997-98) Photo: Adam Reich © Joan Snyder. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

After having Molly in New York in 1979, Snyder left the city over growing fears for her daughter’s safety after a child was abducted near where they were living on Mulberry Street. They moved to a little house surrounded by bean fields in Eastport, on the south shore of Long Island, which inspired Snyder to start painting landscapes in the style of her Stroke pictures. “I made bean field with snow, bean field with music, bean field with mud. And then, interestingly enough, the farmer who owned the bean fields had a stroke and they became weed fields, but they were so beautiful. These fields full of wildflowers,” she says.

Perhaps surprisingly, Snyder thinks of herself as a landscape painter first—though her landscapes often read as figures and vice versa. She recalls, as a young painter, hearing Frank Stella saying he would never put a figure in his paintings. “It inspired me to say I would always put a figure in my painting,” she says. “Who would make a statement like that? With all due respect, and I love some of Frank Stella’s paintings, but that was such a blatant statement, it dismissed a lot of artists.”

Today, Snyder’s studio is full of the remnants and symbols of landscape—dried flowers, petals, straw, mud, berries and rosebuds. She moved back to New York City in the mid-1980s, where she met her now wife Margaret Cammer, a former judge.

These remnants have caused critics and writers to liken her studio to a witch’s den—an analogy that Snyder says amuses her. But there is a distinctly spiritual, alchemical aspect to her work and Snyder herself has spoken about being at an altar when she paints. “It is the altar I go to face myself,” she has said. “Art became a form of worship. Those were my shrines.”

In 1992, Snyder wrote an essay, It Wasn’t Neo to Us. Prompted by the then rising phenomenon of neo-Expressionism, which was largely written about as a new genre invented by male artists such as Julian Schnabel, David Salle and Eric Fischl. Snyder pointed out that artists including Nancy Spero, Faith Ringgold, Jackie Winsor and her had been bringing expression and the personal into their art long before—except they were called feminist.

The text asked if anything had changed for women artists over the past 20 years. “Are we still discriminated against by curators, critics, and dealers? Do we still need to have women’s shows?” Snyder asked.

The same questions are still valid today. Snyder thinks there has been a great deal of progress since the 1970s but says there is still a glass ceiling for women artists. “We’re very far from being considered equals—at least I am—to male painters in the art world. I don’t think there’s equality. Women are still struggling to keep up or to be properly recognised or accepted. Not to mention getting retrospectives and equal sales prices.” It seems things could be about to change for Snyder.