In the same vein, older adults are much more likely to focus their energies on important relationships with close friends and family, and less on peripheral acquaintances. They experience fewer stressful conflicts in these close relationships, and when conflicts do arise, they tend to rate them less negatively. This may explain in part why older adults reported less COVID-related stress than younger people: Their social networks were stronger.

“Once the heart starts pumping, it takes longer for an older person’s body to relax and recover.”

What stress does to the body

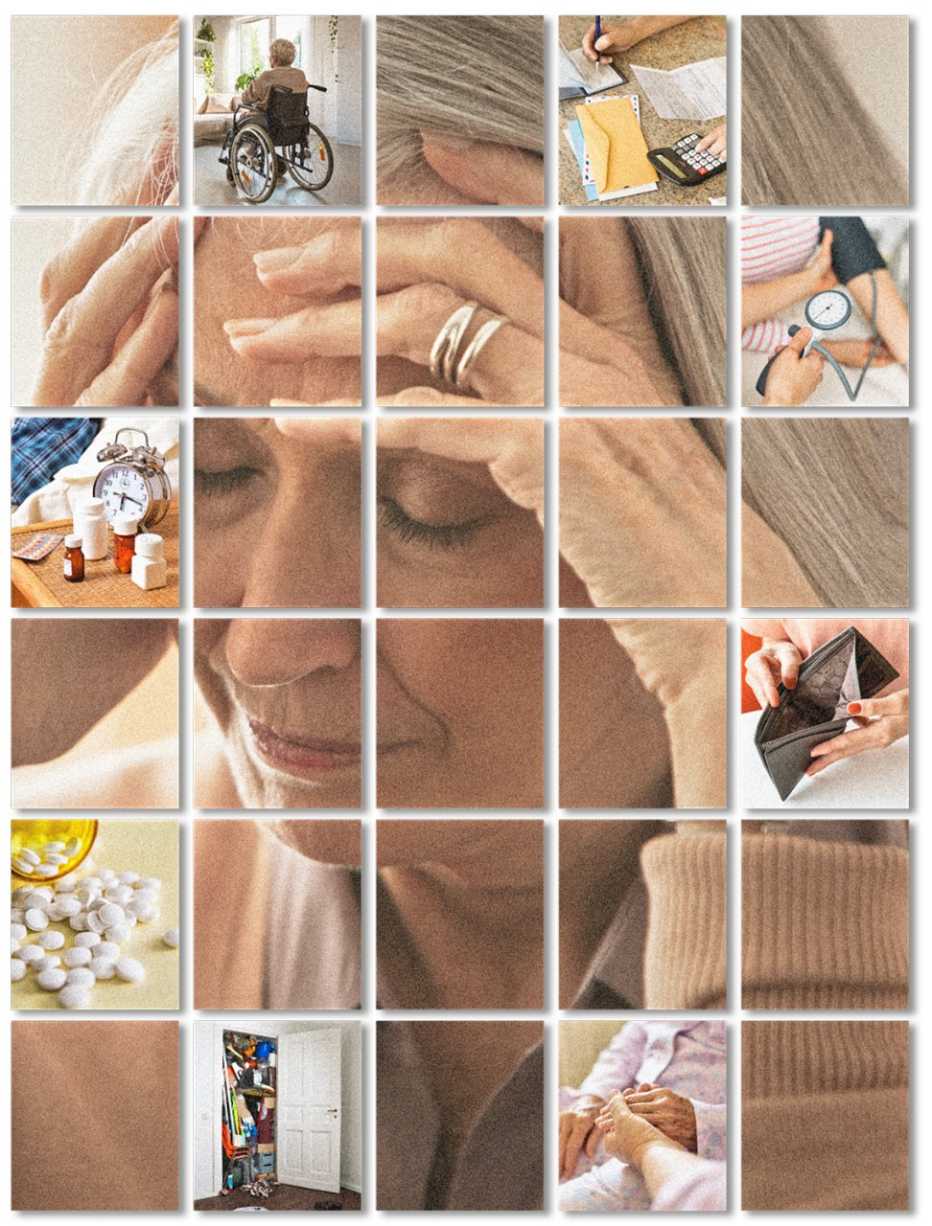

So yes, we grownups have developed techniques for coping with acutely stressful moments — flashes of anger, approaching danger, even the onset of a pandemic. But stress remains an aggressive health foe for us, due in large part to more chronic forms of stress, and the ongoing drumbeat of health concerns, the pressures of caring for ailing relatives, and the increased anxiety around living on a “fixed” income are frequent challenges for older adults.

These high-level challenges have a way of pushing your “stress” button day after day, week after week, year after year. Say you are struggling financially; every time a bill arrives in the mail or you are at the grocery store, instant money fears can trigger the flow of stress chemicals. This can impact the body, especially the older body, which may be more vulnerable because of other health issues, in less detectable but far more consequential ways, Charles says.

Stress response #1: The hormone flood

When the hypothalamus in the brain senses stress, it signals the pituitary and adrenal glands to pump out cortisol — the “stress hormone” — into the bloodstream to help the body respond to threatening situations. Cortisol does a number of things, including increasing inflammatory compounds and clotting factors in the bloodstream, in preparation for possible injury.

Among older adults, the cortisol surge is both stronger and takes longer to return to normal. Studies show that cortisol affects older adults significantly more than younger adults, causing more inflammation. It also impacts our physical capacity, weakening muscle signaling; older adults under stress may find it harder to do something like climb stairs. When the stress becomes chronic, the brain — dense with cortisol receptors — is repeatedly washed with cortisol surges, which become toxic, increasing your risk for developing dementia.

Cortisol also can dysregulate your immune system. In one study, a month of chronic stress exposure was associated with a more than 150 percent greater risk of catching a cold. In another study of financially strained older adults, each day since their last Social Security payment (a significant source of income for nearly two-thirds of older adults) was associated with a significant increase in inflammation, a known predictor of disability and mortality.

Fight the cortisol flood: There are many ways to stem the tide, but one stands out. Studies indicate that “exercise can bring down cortisol levels in the elderly and in people with major depressive disorder,” according to the Cleveland Clinic. Turns out that wonderful feeling that follows exertion is the most healing thing you can do for stress.

Stress response #2: The fight-or-flight instinct

Shutterstock; Getty Images; Hero Images; Stocksy/AARP

The other way our brains respond to stress is by signaling the body to release adrenaline. Heart rate increases, and blood flow shifts, sending more oxygen flowing to the heart and skeletal muscles. Cellular metabolism cranks up to increase energy production, and blood pressure spikes to distribute that energy wherever it may be needed. Other blood vessels constrict, further boosting blood pressure while keeping blood and oxygen flowing to vital organs. This becomes increasingly hazardous as we get older and health issues like high blood pressure become more common.

“Often, with age, we become less physically resilient,” Charles says. “That’s why the older you are, the longer it takes for your body’s core temperature to return to normal. Or when a car flashes its brights, it takes longer for your eyes to readjust.”

The same thing happens when stress hits, Charles notes. “Once the heart starts pumping, it takes longer for an older person’s body to relax and recover.” One study tracked the blood pressure of teachers over the course of a stressful school day. The blood pressure of both young and older teachers was elevated, but at the end of the day, the BP of the younger teachers had returned to normal but the BP of the older teachers had not.

This only makes sense. As we age, our blood vessels become stiffer, while atherosclerosis often sets in, impeding blood flow. That explains why the stress response among older people is more likely to cause a stroke or heart attack: The greater the abnormalities in the vasculature, the more dangerous a sudden increase in blood pressure may be.

Ground fight or flight: Older adults have some advantages in calming the sympathetic nervous system, because acquired wisdom can help us notice stressful patterns and practice acceptance. “Reframing” a perceived threat brings it down to size. In one study, older adults who participated in an eight-week mindfulness training reduced their risk of depression by more than 50 percent.