The season of giving has come and gone. There were countless charitable causes to support, but just because you think a client has donated lots of money or other assets, the tax courts won’t necessarily agree. Let’s walk through how recent tax court cases change the valuation landscape for donations and beyond.

Say one of your clients runs a successful private company. One of her children loves dogs, and the other child wants to help cats. Since most parents claim they don’t have “favorite” children, it’s natural for your client to want to donate 50% of their company to a dog-friendly organization and 50% to a cat-friendly organization. Unfortunately, this 50/50 split results in a significant loss of tax deductibility.

Here’s why.

The 2021 court case of Warne v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2021-17 (Warne), teaches us a great deal about charitable gifts, valuation discounts and how the structure of a donation can lead to an unexpected tax bill.

There are two important questions at the crux of Warne:

-

Do discounts for lack of control (DLOC) and marketability (DLOM) apply to controlling interests?

-

What is the correct measure of a charitable contribution’s value? Is it the value given up by the donor or the value actually received by the charity?

Background of Warne

In Warne, the decedent owned 100% of a closely held company. The estate executed the decedent’s charitable plan by splitting ownership between two charitable foundations. One charity received 75% of the company, and the other received the remaining 25%.

At first glance, this seemed straightforward. The estate believed it was donating the full company, so it expected a charitable deduction equal to the total value of the business. Because the interests were transferred separately, however, each needed to be valued independently. The taxpayer expected that the total deduction would still equal 100% of the company’s value. The IRS and tax court disagreed.

Discounts on Controlling Interests

As mentioned earlier, the first issue in Warne was whether DLOC and DLOM (i.e., minority discounts) could apply to controlling interests. It is important to note that the IRS applied these minority discounts to the 75% interest. The IRS wanted lower values for estate-tax purposes. The tax court did not specifically rule on the issue, and the language of the opinion reflects skepticism, although it was passively accepted. The tax court only ruled on contrary perspectives. As such, while the tax court technically provides support for the application of discounts for lack of control and marketability, we find it uncertain whether future courts will uphold that opinion.

Determining the Deductible Basis

The second issue involved the method for calculating the value of the taxpayer’s charitable contribution. Specifically, what was the basis for the deduction? Was it the consideration received by the recipient, or was it the consideration lost by the donor? Said another way: if you donate an asset that’s worth a lot to you — but of minimal value to the charity — how much can be deducted?

Consistent with the definition of fair market value (FMV), the tax court ruled that the value received by the charity was the basis of the deduction. Warne involved the donation of a 100% interest in a company. However, the donation was split between two charities, with one receiving 75% and the other 25%.

While the taxpayer argued that they donated their entire company to charity and that the total deduction should be equal to 100% of the company’s value, the tax court disagreed. Instead, the tax court ruled that the 75% and 25% interests had to be valued independently, considering DLOCs and DLOMs for each interest. This methodology resulted in a lower FMV for the deduction than the FMV included in the estate.

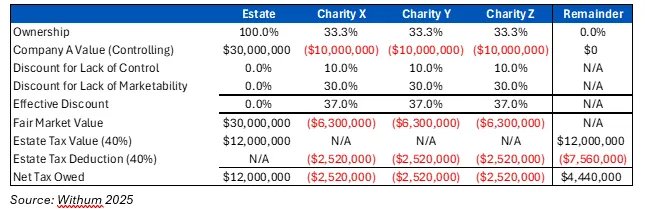

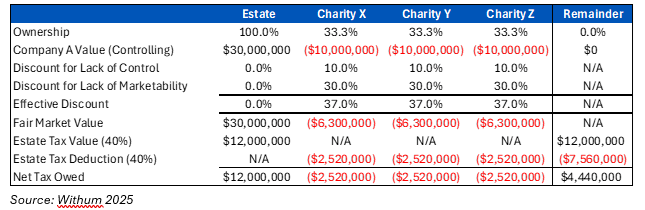

Real World Example of Tax Savings

Let’s assume an estate has no remaining exemption and that its only asset is a 100% interest in Company A with a FMV of $30 million. The estate owes $12 million in estate tax prior to any deductions. But the estate donates its interest in Company A equally to Charities X, Y, and Z with the intention of offsetting its estate tax owed. However, the donated assets have a lower value than the aggregate interest in the estate due to minority discounts. After the application of these discounts, the effective charitable deduction is $7.6 million. This leaves the estate with a net estate tax due of $4.4 million, highlighting the downside of poor execution of charitable planning. See the illustration below.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Warne introduced two important takeaways for financial advisors and estate planners. First, it suggested, though not definitively, that even controlling interests may be subject to DLOC and DLOM adjustments. This challenges traditional assumptions. Second, Warne highlighted the substantial tax risks that can arise from poorly structured charitable donations. To avoid unintended tax consequences, advisors must guide clients toward more strategic giving, whether by donating clearly controlling interests or opting for liquid assets. Proper planning is essential to ensure that generosity does not come with an unexpected tax bill.