Robert Newland, whose work as a financial adviser for the convicted art fraudster Inigo Philbrick helped the latter scam clients out of tens of million of dollars over a multi-year period, was sentenced to one year and eight months in prison by a New York district court judge on Wednesday (19 September).

Newland, who pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud last September, had been permitted to await sentencing at his home in London under curfew. Newland’s wife and one of his brothers appeared at court in New York Wednesday to support him, as did an unnamed former colleague from his most recent job. Newland’s young children did not attend, as he and his wife did not want to subject them to the proceedings, his lawyer, Roger Burlingame, said.

Judge Sidney H. Stein said Newland had until 1 December to surrender himself into custody. The court recommended Newland be transferred to the UK to serve out his sentence, though it will ultimately be up to the US Department of Justice. After the prison sentence, Stein recommended that Newland be subject to two years supervised release and 200 hours of community service for each year of the supervised release period.

Newland was also ordered to pay $67.5m in restitution, along with forfeiting an untitled 2006 painting by Mark Bradford. He had previously agreed to hand over $76,000 in cash as well as a Jean Prouvé desk and three paintings all acquired through his dealings with Philbrick before the fraudulent behaviour began: Carroll Dunham’s Personal Distance A, an untitled Christopher Wool painting from 2016 and an untitled Wade Guyton work from 2007.

Prosecutors said in a memo filed with the court earlier this month they would seek less than Philbrick’s seven-year prison sentence, but that Newland’s punishment should still be severe enough to deter others from preying on the art market, which they described as “ripe for abuse by fraudsters” due to its minimal oversight. (Stein said Wednesday that Philbrick is only expected to serve between 48 and 49 months in prison before his supervised release begins.)

“This combination of conditions—secrecy, valuable assets, lack of regulation and the commoditisation of art—creates opportunities for fraud schemes such as Philbrick and the defendant’s scheme,” prosecutors wrote. “A meaningful custodial sentence is necessary to send a corrective message and restore some measure of faith in the proper functioning of this valuable, but unregulated market.”

While prosecutors acknowledged Philbrick was the “instigator and driver of the scheme”, they emphasised that Newland’s actions enabled the fraudulent behaviour to continue longer, amplifying victims’ losses. One of his primary contributions was the creation and maintenance of spreadsheets tracking the share of co-investment in artworks ostensibly controlled by Philbrick, with the combined claims sometimes surpassing 100%.

“The defendant used his financial expertise and credentials to give credibility to Philbrick’s art business, thereby encouraging certain investors and lenders to invest with Philbrick. The defendant also used his financial expertise to extend the life of the fraud by strategising how to maximise profits in order to prioritise paying back certain victims without disclosing the fraud,” prosecutors wrote.

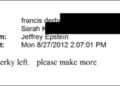

Newland himself supported the prosecution’s portrayal of his impact in a letter to the judge filed last week. Alternating between lamentation and contrition, Newland recounted how he gradually descended deeper and deeper into Philbrick’s scams over a multi-year period, from looking past red flags in Philbrick’s handling of accounts, to forwarding creditors documents that he knew to have been altered by Philbrick, to eventually sending emails in the guise of a fictitious collector named Martin Herrero, a character dreamed up to paper over the duo’s frauds.

“At every moral crossroad, as the stakes got bigger and bigger, I took the coward’s way out by continuing the lies rather than facing the consequences,” Newland wrote in his letter. “I am ashamed and disgusted by what I did. No matter how many times I run though it, I struggle to come to terms with the fact that I allowed my ambition (and greed), and then latterly, in 2017, my fear, to overcome my moral compass.”

Of the $86.4m in fraudulent art deals that Philbrick executed over a four-year period, prosecutors accused Newland of directly participating in about half over the course of two years. Many of the victims—which include the Berlin-based financial-services firm Fine Art Partners and the US-based art lender Athena Art Finance—are unlikely to recover their lost assets. Cecilia Vogel, a lawyer for the US Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of New York, reminded the court during the hearing that multiple civil lawsuits against Philbrick are still ongoing, and that some of the works of art at issue have yet to be located.

Newland met Philbrick when both were working for art dealer Jay Jopling, the founder of the London-headquartered mega-gallery White Cube. Before being hired as a commercial director there in 2012, Newland had worked as a consultant at McKinsey & Company and as a strategy manager at Christie’s auction house. In 2013, Jopling backed Philbrick in launching a secondary-market dealership, Modern Collections, and by the following year Newland was named a commercial director of the company, a position he held until the end of 2016.

Newland opened his own consulting business, Arcora Advisory, in 2017, with Philbrick’s gallery as his main client. He also personally invested in multiple deals constructed by Philbrick over the years. Newland later worked with the mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth from November 2018 through November 2019. When he was indicted in February 2022, he had moved into a sales director role at Superblue, the Miami-based art and tech centre specialising in experiential art installations.

Jopling eventually became another victim of Philbrick and Newland’s illicit dealings. He and the partners at White Cube were also among the absent parties Newland apologised to before the court prior to the announcement of his sentence, saying: “When the time comes, I will struggle to look him in the eye.”

Stein explained his rationale for the sentence by describing the 20-month prison term as “appropriate and appropriately substantial”, but recognised throughout the proceedings that Newland was remorseful and introspective.

Stein ended the sentencing by addressing Newland directly. “You’re going to be OK,” the judge said. “I don’t think I’ll ever see you again. Good luck to you.”