Africa’s stability is inextricably linked to international peace and security. For that reason, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meet annually as part of their partnership agreement. But considering current threats to global security and heightened risks of coups and terrorism in Africa, the 6 October gathering produced little of substance.

Globally, there are widening cracks in the multilateral system, with the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Palestine wars raising questions about the UN’s role in maintaining peace and security.

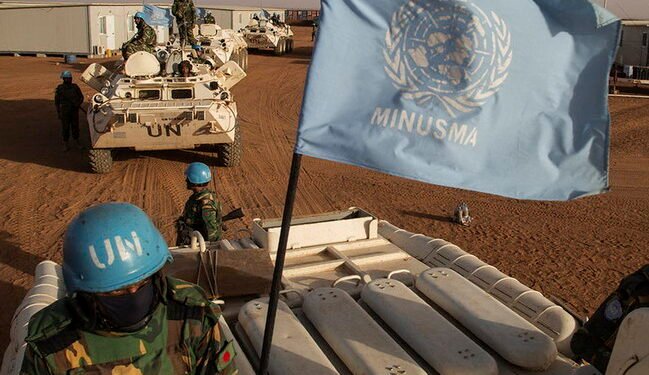

In Africa, the dangerous resurgence of coups in West and Central Africa signals deep governance and democratic dysfunction. As the threat of violent extremism grows across the continent, the withdrawal of peacekeepers from Mali and soon the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is creating security voids and the likelihood of further instability. Meanwhile, funding shortfalls hinder the operational effectiveness of various peace operations, leading to their premature drawdowns, as in Somalia.

This context calls for decisive action to halt Africa’s deteriorating security outlook. The UN-AU consultations considered the conflicts in Sudan, the Sahel, the DRC, and Somalia, along with the activities of the AU Transition Mission in Somalia. The two councils also discussed financing AU-led peace operations, the role of youth in peace and security, and better working methods for PSC-UNSC cooperation.

But the agenda wasn’t in step with Africa’s complex security challenges. It was dominated by the situations in Sudan, Somalia, the DRC and Sahel. While these joint priorities needed to be discussed, other pressing crises didn’t feature. These include Mozambique’s ongoing insurgency, and in Ethiopia, hostilities in Oromia and Amhara regions and new challenges facing the Tigray peace process. Their exclusion underlines that the agenda-setting function of these UN-AU meetings must be widened to look beyond just a few cases.

Broader discussion on the need to prioritise conflict prevention and early response to emerging conflicts, and the inclusion of rotating cross-cutting thematic issues, could make the consultations more relevant.

Thematically, the agenda’s omission of the resurgence of coups and unconstitutional changes of government – even in the informal discussion segment – raises questions about both councils’ priorities.

Last year, countering terrorism was rightly discussed in the context of West Africa and the Sahel’s deteriorating security and political situation. This year’s meeting did well to cover the untimely withdrawal of peacekeepers, but the question of supporting transitions within the context of growing coups should have been dealt with.

The two councils focused only on coups in the Sahel, leaving out Gabon. This is interesting given that Gabon – which currently serves on the UNSC despite being suspended from the AU – was allowed to attend the meeting. That raises questions about the nature of the AU-UN partnership and signals the two institutions’ divergent approaches in handling such controversial issues.

Gabon’s suspension from AU activities should arguably have barred it from attending the council-to-council consultations. A member state representative who requested anonymity suggested to ISS Today that the meeting wasn’t really an AU session but one hosted jointly by the two inter-governmental bodies. So Gabon could attend as a UNSC member.

Based on its joint communiqué, the UN-AU meeting delivered surprisingly little concrete action on how to resolve the crises considered. Some member states and observers said expectations that key decisions would come from the consultations remained largely unmet.

The meeting did hint that progress was being made on the years-long matter of funding for AU-led peace support operations. The issue is one of the major ongoing challenges facing both bodies.

In February, the AU adopted the AU Consensus Paper on predictable, adequate and sustainable financing for AU peace and security activities. And the UN Secretary-General’s May 2023 Report supported access to UN-assessed contributions, as did the PSC ministerial meeting on the margins of the UN General Assembly in September.

The AU has also revitalised its Peace Fund, signifying greater ownership of its security priorities. There are indications that the UNSC may not insist on the AU footing the 25% financial contribution for peace operations, which could be sourced from member states and partners such as the European Union and China.

Most importantly, a draft resolution on the funding issue is expected to be considered by the UNSC in December. Its adoption will strengthen the AU-UN partnership and enable UN-authorised AU-led peace missions to deal effectively and appropriately with the challenges they confront.

As a consultative meeting, the UN-AU gathering may not be expected to deliver hard results. But to be more relevant, deficiencies in agenda-setting need to be addressed. The consultations must acknowledge that solutions to Africa’s multiple crises lie largely in prevention. And there should be a move away from the selective focus on a few country- and region-specific cases.

To avoid these important meetings being seen as mere deliverables on the annual calendar, member states that can champion particular issues should be tasked with information sharing and joint messaging.

Written by Hubert Kinkoh, Researcher, African Peace and Security Governance, ISS Addis Ababa.

Republished with permission from ISS Africa. The original article can be found here.