Fewer people have explored the deep ocean than have been to the moon.

Underneath the surface of the water, you can find mud volcanos, vast canyons and a range of rare and fascinating sea creatures.

This is the world in which both Ila Glennie, BP’s VP of subsea and Anch Klein, VP wells regions work.

Glennie’s team supports any BP development activity underwater, whether it’s oil and gas or increasingly offshore wind and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

She joined BP as a graduate and started work on projects West of Shetland including Foinaven and Schiehallion.

Then, working in 300m of water depth was considered “really challenging”.

“Now we have projects in 3,000m of water depth,” she said.

“It is quite incredible how we have been able to advance and push the boundaries of the technology and get to grips with the unique conditions that presents.”

Oil and gas to clean energy

BP is making inroads into offshore wind and carbon capture and storage (CCS). In the UK, the firm is developing the 2.9GW Morven offshore wind farm with partner EnBW as well as the smaller, more experimental Flora floating offshore wind scheme.

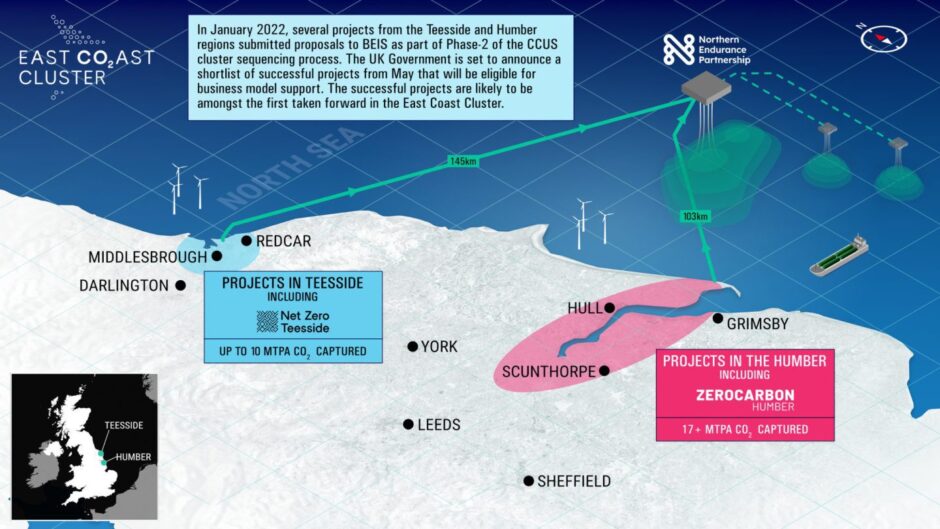

It also has involvement in CCS projects which will inject carbon back into the ground beneath the sea, including the Northern Endurance Partnership (NEP).

This is a plan to store carbon emitted by polluters from across the Humber and Teesside region 145km offshore into Endurance, the UK’s largest appraised saline aquifer.

The need to explore further and deeper is pushing the boundaries of technology.

“In order to plan an offshore wind project we have to understand the seabed, the metocean [meteorological and oceanographic] conditions,” said Glennie.

“Because of the scale of some of the offshore wind developments and the volume of data that is needed, that has really helped us to drive new way of doing things.”

New ways of working include using un-crewed surface vessels which are going some way to redefining “work from home” for some BP employees.

“These vessels are remotely piloted – sometimes from someone’s home other times from a remote operations centre.

“But our ability to acquire data and quickly visualise that data is really helping us in the offshore wind area.”

She added: “It’s something we have learned in the offshore oil and gas industry, is that is really good quality early engineering data leads to much better outcomes for the project.”

Threading the eye of the needle

Klein’s team works all over the world wherever wells need drilled, in Brazil, Egypt, Senegal, as well as the Net Zero Teesside project in the UK. Both BP teams work together on the NEP.

It is part of the UK government’s “Track 1” CCS programme and Klein says the partners are on track for a financial investment decision (FID) this year.

Instead of extracting oil and gas, this is about injecting around 1m tons per annum of CO2 back into subsea wells.

The project will involve six well constructions – five for injection and one for monitoring.

“Injection wells are not unheard of by any means. We have used injection wells for water injection, gas injection, and cuttings reinjection. It is not unknown technology,” said Klein.

“But it is drawing on this high-skilled team. We are taking these skills into how we can safely construct the wells.

“We are using this expertise to shape our understanding. It’s a bit ground-breaking in terms of technology.”

The southern North Sea has also been identified as an increasingly busy area. Klein says the well drilling operations will be designed to be “fishing friendly” and there are plans for an offshore wind farm nearby too.

Klein too has seen how technology has transformed drilling operations since she first started in the industry in the 1990s.

She likens abilities now as being like “threading the eye of a needle from five metres away”, which anyone who has knowledge of sewing will appreciate the difficulty this presents.

Not to mention, this threading is often undertaken remotely.

Recently in Senegal, her team oversaw the installation of a number of 80-ton subsea “Christmas trees” which had been built in Scotland and shipped over to the site then lowered 3km down to the seabed “with pinpoint accuracy”.

“When you talk about ‘big engineering’ that is exactly it.

“This is not small stuff we are doing here. These are critical wells for a multi-billion dollar project. Accuracy is everything.”

Overcoming challenges above and below

Back in Teesside, the challenge is also establishing the ground rules with the alphabet soup of government and industry regulators.

This includes the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM)

“It’s about fostering those relationships,” said Klein.

“It is an industry that is gaining ground and opportunity both for jobs and our knowledge.

“It makes it really exciting. And I think it has generated a lot of excitement, frankly, in the wells community. All of our young engineers are saying, right, I can make a difference in this space. I can use the skills I’ve got today.”

Glennie said their teams are asking the key questions the entire energy system is facing as it makes the transition from oil and gas to cleaner forms of energy.

“How can we use what we already do to test and try and advance techniques that can then make offshore wind and CCS and other energy projects more economic, or improve cycle time?

“Can we keep advancing our survey and site techniques, our reliability and maintenance?

“Can we try out new technologies and techniques on our existing subsea infrastructure that will help unlock some of these projects in the future?”

Alongside technical challenges are also financial ones. Oil and gas prices can be volatile but projects are designed to make profit through commodity price changes.

Renewables, which are funded and regulated much differently require technology solutions that are both highly improved but at a lower cost.

“We are doing offshore wind and CCS projects that have a different set of economics – have lower margins and regulated from a financial point of view so there isn’t the same upside that we are perhaps used to talking about for oil and gas type projects.

“They are going to have to develop more efficient, lower cost techniques. Keep pushing the boundary on remote operations, on remote monitoring and surveillance, on data analytics.

They are going to have to develop more efficient, lower cost techniques. Keep pushing the boundary on

“And as those techniques are developed how can we bring that back to oil and gas?

“I see it as a two-way exchange between our traditional energy areas and our new energy areas.

“That is something I find exciting.

“It will be a transition. We will continue doing both in parallel side by side and how can we really get that feedback look learning and exchange of technology on an ongoing basis and that is what I look forward to and see happening.”

Fostering creativity

The first offshore rig she stepped foot on in 1990 left a lasting impression on her. “It was really big engineering. My eyes were opened up to this amazing world.”

There was a sticker on the rig that highlighted the prevailing conditions which said: Deep, cold, rough.

“I felt an affinity a connection.

“There’s something about that challenge that really appealed to me.”

Klein was the only woman on that rig and one of two women on her engineering course out of 60.

“You just kind of get used to that dynamic. But it doesn’t mean to say it’s the right dynamic. I think we are making genuine strides to change that. We have some huge ambitions at BP to make a significant change in this space.”

Glennie was also “often the only woman” offshore.

She said back then, in her days as a junior graduate engineer, she didn’t feel empowered to speak up to address issues. But now she does.

“Now, in a leadership position, it’s absolutely my role to identify and create an inclusive supportive environment where issues can be brought up and addressed.”

Klein added: “It is not rhetoric, this is reality. We encourage speak up. The more as leaders we talk about it and share our stories – I think it’s about showing your own humanity.”

Now leaders of the business also focus on how women are being treated offshore.

She added. “There’s something about being very objective about that. It has actually caused everyone to think we need to make sure this is catered for.”

Glennie: “I think it is really important there are visible role models and gender is one aspect of that. But I think having a diverse leadership team, does foster the creativity, the innovation the performance that an organisation like ours needs.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Ila Glennie/ BP

© Supplied by Ila Glennie/ BP © Supplied by Net Zero Teesside

© Supplied by Net Zero Teesside © Supplied by BP

© Supplied by BP © Supplied by BP

© Supplied by BP © Supplied by Anch Klein/ BP

© Supplied by Anch Klein/ BP