BP’s (LON:BP) undressing of its energy transition goals is the latest and most significant example of an oil supermajor reneging on its green investment pledges.

It is easy to speculate that companies such as BP, and similarly Shell (LON:SHEL), have attempted to diversify into renewable energy too quickly. However, diversification in the energy transition could be the very thing that pulls the cart out of danger.

This week, BP’s chief executive Murray Auchincloss defended the company’s decision to jettison renewable energy pledges and increase oil and gas production.

In late February, he said the oil major had accelerated “too far, too fast” in the transition to renewable energy. “Our optimism for a fast transition was misplaced,” he said, after profits fell across its low-carbon and gas division, precipitating a sudden strategic about-face.

The company, which has been under pressure from analysts and shareholders to reduce its low-carbon investments and double down on its core business of oil and gas, plans to cut investment in low-carbon projects by $5 billion (£4bn), Auchincloss said.

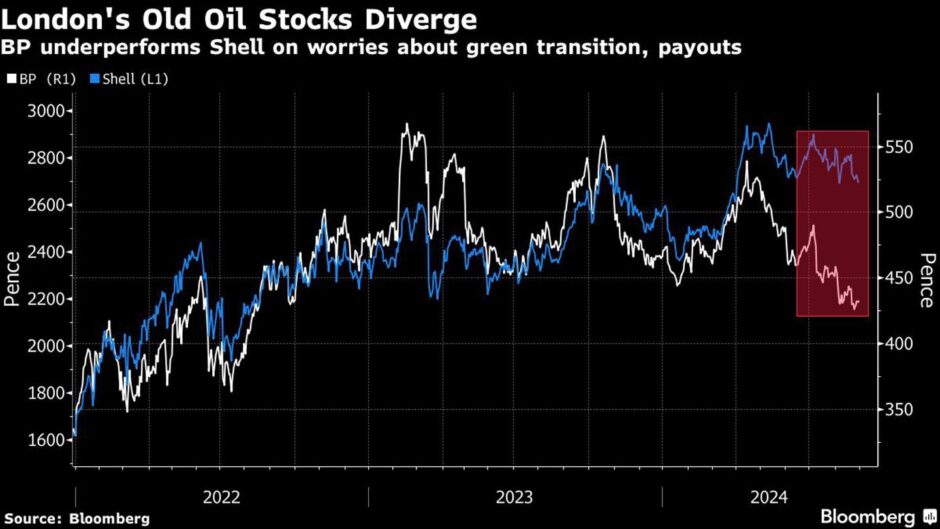

“The challenge that faces BP and Equinor, and to varying degrees Shell and Equinor, is the underperformance of their shares relative to that of their US peers,” says Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell.

“Whether this is down to the greater emphasis they have placed upon investment in renewables to facilitate a move away from hydrocarbons, or simply down to their stock market domicile (given how US equities continue to dominate across the board) is hard to divine, but the truth may lie somewhere between. There is a sense that shareholders are becoming restless.”

BP’s shares have shown a marked underperformance relative to global peers since former CEO Bernard Looney announced a major pivot away from hydrocarbons in August 2020.

While in the past five years, BP’s share price on the London Stock Exchange has risen by more than 50%, its shares have slumped 14% in the past year and now trade at 421.4 pence per share.

US rival Chevron’s (NYSE: CVX) share price has comparatively stayed flat at US$153.61 per share over the past year and surged 84% in five years.

BP’s former chief executive Looney had planned to cut the production of hydrocarbons by 40% and increase investment in wind power, solar, hydrogen and other areas of clean power.

In 2023, BP revised a plan to cut oil and gas production by 40% to 25% by the end of the decade, while (at that time) leaving the long-term net-zero target unchanged.

BP shares ‘lagged’

While Looney had already begun to scale back those commitments before he was ousted by the board in 2023, BP’s unravelling of its low-carbon targets took hold with the installation of Auchincloss that year, who began to scale back low-carbon investments after he was appointed interim chief executive.

The oil company was rocked last month when notorious activist hedge fund Elliott Investment Management took a stake in the firm just a week before its capital markets day, after its shares had “lagged” American and European peers.

The activist investor took a nearly £3.8bn stake of almost 5% in the company, in an apparent effort to wrest control from the board.

Analysts predict that the activist could call for a management reshuffle or a sale of assets. Elliott is expected to agitate for change – for example, by calling for a strategic asset disposal or spin-off, or a break-up of the company or bid.

There is growing pressure on executives at traditional energy companies to address “the perception that renewables projects offer lower returns on investment”, says Mould.

That pressure to appease shareholders may prove too great, as in Auchincloss’s case, his pay fell by one third from £7.7m in 2023 to £5.4m in 2024, with a drop in his bonus from more than £1.1m to £734,000.

According to analysts, BP paid out estimated dividends of £5.2bn in 2024, less than the total dividends issued by TotalEnergies of £7.7bn and Shell at £8.7bn – with ExxonMobil’s the highest estimated annual payout at £16.7bn.

“The dilemma is that oil firms have the cash flow and resources to invest in these projects and help to ease the transition, but it is not clear whether they can do so while maintaining the returns on capital and cash returns,” says Mould.

In recent commentary, he speculated that activist investor Elliott “wants BP to clarify its strategy on oil and gas production, renewable energy and the future direction of the group”.

Revealing BP’s Q4 results, Auchincloss said it had been “reshaping” its global portfolio, “sanctioning new major projects” and “focusing our low-carbon investment” with a cost reductions key to the changes.

The company has hinted at plans to potentially sell off its US onshore wind business and recently consolidated its offshore wind portfolio, forming a joint venture with Japanese firm Jera, in a bid to reduce capital investment.

No ‘automatic right’ to win

Auchincloss unveiled a net-zero “reset” of BP’s business in February, but kept in place the company’s 2050 net-zero emissions target.

Ashley Kelty, natural resources analyst at Panmure Liberum, said: “A fanfare of changes had been promised, but in all honesty it is an underwhelming reset for the company.

“There was the expected pivot away from lower margin renewables back to investment in core oil and gas. This will see increased investment of $10bn annually in fossil fuels, with spend on low margin renewables slashed by c$5bn annually to $1.5-2bn. However, this means that overall capex will fall from prior guidance of $14-18bn to $13-15bn.”

He said the “increased upstream activity is targeting growth in production” and “to get reserve replacement from current 50% to over 100% by 2027”.

“This is likely to be very challenging given the recent underinvestment in O&G and the long timelines to get discoveries into production,” said Kelty.

He suggested that activist investor Elliott will look to unseat Auchincloss and chairman Helge Lund for not taking the “radical” step of axing its renewables business entirely.

BP appears to have costed in its deliverables tightly, with little room to manoeuvre. As Kelty points out, overall spending is declining, and a fall in spending can indicate lower potential for future growth.

In December, the company scaled back its investment in offshore wind in a bid to reduce capex. As part of its strategic “reset”, it is also expected to sell a stake in solar power producer LightSource BP, after finalising a takeover of the renewables business just last year.

BP may find that it is hamstrung without investing in growth, while tightly pricing its costs. Kelty warns that BP has made “some pretty challenging assumptions on pricing” that leaves it with “no margin for error if commodity prices fall”.

While some analysts have called for a “radical shift” in abandoning renewables entirely to make the company more “attractive to investors”, without investing in growth the company risks becoming irrelevant in a changing world.

“BP is now recalibrating its strategy and more emphasis on ensuring it generates the best value from its oil and gas assets, given how the pace of transition toward renewables is taking time, owing to the challenges involved in connecting new energy sources to the old, existing grid,” says Mould.

“Whether this is enough to satisfy all shareholders is unlikely – some will be disappointed by the slower pace of progress, others will be frustrated by how BP continues to try and ride two horses at once. There are reports that Elliott continues to push for a total spin-off of the renewables operations.”

In October, BP issued a profit warning indicating that quarterly oil trading had slumped, but that electric vehicle charging was expected to be a growth area for the multinational business.

By January, BP had announced it would cut more than 5% of its global workforce in pursuit of “value”, just a day after UK energy secretary Ed Miliband said the UK government would consult on plans to stop issuing new oil and gas licences.

“The issue, thus far, has largely been one of share price performance relative to the other global majors and the American ones in particular – CVX, XOM and COP. There is a perception that BP tried to move too quickly away from hydrocarbons and thus had put itself at risk of failing to maximise the value of its existing assets,” says Mould.

“Additional, there are concerns that renewables require different skillsets (and bring a different customer base) relative to oil and gas exploration and production, with the result that operational risk is higher at a time when return on capital employed in renewables could be lower than that earned from hydrocarbon production.”

In a letter to employees explaining the headcount reduction, Auchincloss nevertheless highlighted a need for the business to accelerate in the energy transition.

“We are uniquely positioned to grow value through the energy transition. But that doesn’t give us an automatic right to win,” Auchincloss told employees.

Shell’s ‘ruthless’ outlook

Last year, Shell chief executive Wael Sawan promised a similarly “ruthless” focus on generating returns, retiring a goal of reducing net carbon intensity by 45% by 2035 and watering down its emissions-reduction target for oil to 15-20%.

On 30 January, Shell posted adjusted earnings of $3.66bn for the final quarter of the year, down from the $6bn of earnings that it posted in the third quarter.

Again, it was under pressure financially. Its annual earnings slumped to nearly £23.72bn in 2024, down from £28.25bn in 2023, while it reported a loss in its renewables and energy solutions business. Installed renewables capacity remained almost flat on the prior quarter at 7.4 GW.

“Shell’s fourth quarter revenue fell from $78.7bn to $66.3bn,” says Hargreaves Lansdown’s head of equity research Derren Nathan.

“Underlying profit halved to $3.6bn, falling short of analyst expectations. The weak performance reflected lower margins in its trading businesses as well as the marketing division. Lower oil prices also played their part as well as non-cash write offs of exploration wells.”

Shell’s main focus “remains very much on oil and gas”, says Nathan, who warned that unpredictable oil prices will be a “crucial element” of the group’s fortunes, adding that Shell is “not a one-trick pony”.

“In distribution, Shell is particularly well placed to provide lower-carbon options to motorists,” Nathan said. “Its global network of 47,000 service stations is the largest of all the oil majors. By 2030, it’s hoping to nearly quadruple the size of its Electric Vehicle charging estate, to around 200,000 connection points.”

Ultimately, energy companies understand the value of transitioning their businesses to keep pace with market adaptation, as demonstrated by Auchincloss’s pithy comments.

In the coming decade, they will likely face the extinction of new oil and gas exploration licences and a phase-out of petrol cars, if the Labour government honours its pledges to do so.

But as they grasp onto new vines, they continue to cling tighter onto their existing holdings – putting them out of step with the wider policy climate. Whether this proves to be the right strategic decision, only time will tell.

The first article in this series examined whether oil supermajors are positioned to survive the energy transition.

Recommended for you

© Image: Bloomberg

© Image: Bloomberg © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Supplied by Brandalism

© Supplied by Brandalism © Supplied by Shell/BP

© Supplied by Shell/BP

© Supplied by House of Lords

© Supplied by House of Lords © Bloomberg

© Bloomberg