“What brings you to the Claremont Hotel?” the receptionist asked. “I’m here for Atlanta Art Week,” I replied. “What is that? And does it include booze?” the receptionist asked, with a laugh. The Claremont Hotel was the official hotel partner for the citywide art event that, in its second iteration (2-9 October), brought together more than 40 local art spaces and organisations to elevate the city’s profile on the global art scene.

The second edition of Atlanta Art Week (AAW) boasted special programming—from the first public opportunity to explore the Mildred Thompson Estate to tours of Mercedes-Benz Arena’s sports-centric art collection—free talks (one of which, full disclosure, I participated as a panellist), extended hours at major institutions including the High Museum of Art and Spelman College’s Museum of Fine Art, and evening events at the city’s galleries like whitespace, Jackson Fine Art, Johnson Lowe, Spalding Nix, September Gray and Arnika Dawkins. “We try to be as easy and accepting as possible,” says Kendra Walker, the founder of AAW.

The event is intended as a means of educating Atlanta’s art-curious citizens, creating access to the local art scene and breaking down the elitist boundaries too-often put up by art spaces. Those boundaries, whether perceived or real, can serve to intimidate or actively exclude communities, particularly communities of colour, which make up the majority of Atlanta’s population—the city is 50% Black, while 14% of its citizens are foreign-born.

Across the city’s entire art sector—from artists, dealers and collectors to administrators and curators—one need overrides all others: “continuous exposure and education”, as Walker puts it. AAW, she says, “has definitely exposed a different audience to these galleries and institutions, and made things feel a bit more accessible”. This knowledge gap does not reflect inertia or a lack of activity, though. The national art press has declared Atlanta to be one of the US’s next great art cities and an important mine for talent (Shara Hughes, Lauren Quin and Radcliffe Bailey all hail from there).

Finding the missing pieces

The city has many of the essential criteria for nurturing and sustaining a thriving arts scene. There are robust communities of contemporary artists centred around studio complexes and collectives like Murphy Rail Studios, Temporary Studios, Day & Night Projects and Atlanta Contemporary as anchors. There is significant corporate wealth and plenty of executives with walls and portfolios to fill—15 of Georgia’s 17 billionaires live in Atlanta. A set of active local collectors (including Kent Kelly and Sara and Jon Schlesinger) travels to global art hubs to build their collections. Several major educational institutions and historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) have excellent art programmes and museums. Art publications including Burnaway and Arts ATL provide crucial coverage and critical dialogue around the local and regional scene. And the city has developed a substantial-yet-sui generis art market that’s historically operated outside the global one.

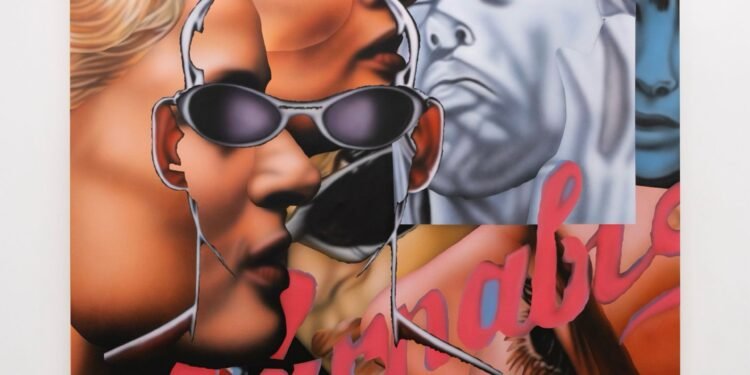

Alic Brock, Marijuana Makes You Flat…Not Fat, 2023 © Alic Brock; Courtesy the artist and Wolfgang Gallery

Another key piece of the puzzle will land next year during AAW: the Atlanta Art Fair, which is being launched by Art Market Productions and Intersect Art and Design (whose chief executive, Tim Van Gal, lives in Atlanta but declined to comment on the new fair). Earlier this month, as the news of the fair broke, the self-described “dealer and broker” Courtney Jewett Bombeck says she received 24 texts within an hour from Atlanta’s top collectors, dealers and power-brokers with opinions and reactions. Exclamations of surprise rang in rapidly, followed by one daunting question: “Who’s going to travel to Atlanta for an art fair?” The city’s art scene struggles to be taken seriously—even, sometimes, by itself.

“I’m sure you’ve talked to people that are very suspicious,” says Donovan Johnson, director of the Johnson Lowe Gallery and an avid supporter of the Atlanta Art Fair. “People here may not have had as long an experience as people in New York with collecting, but they do things really well.”

The shadows that New York and Los Angeles cast are long and frame taste levels and access points across Atlanta. This dynamic frustrates some of the younger, non-white newcomers to the city’s art community. “I don’t want [Atlantans] to start collecting like people do in New York,” Johnson says. “I don’t know that Atlanta being a New York subsidiary is interesting.”

Johnson took over Johnson Lowe Gallery last year, per the wishes of gallery founder Bill Lowe (who died in 2021). Lowe had a reputation as something of a swindler, which was cemented in 2015 when he pleaded guilty to three charges of criminal activity for withholding payment to more than a dozen artists, totalling $561,000. Johnson rebranded the gallery, adding his name and relaunching with a programme favouring artists who are Black and queer.

For the first exhibition in this new chapter, back in March, Johnson engaged New York critic Seph Rodney to co-curate The Alchemists, an exhibition that included Atlanta artist Michi Meko and big names Sanford Biggers, Mark Bradford, Ebony G. Patterson and Yaw Owusu. The show was a powerful gesture that didn’t sell out in the end but “brought in people to the gallery who otherwise would not have”, says Johnson. “There’s something in Atlanta that’s happening, and it’s getting a lot more people to engage with the art.”

During AAW, Johnson opened In Unity, As Division, the gallery’s showcase of seven emerging Atlantan artists. The 7,000 sq. ft gallery was packed shoulder-to-shoulder during the 6 October opening. The featured artists include locally buzzed-about Sergio Suarez, the Congolese transplant Masela Nkolo and Ellex Swavoni, who is part of the Temporary Studios collective—which was founded by locally famous artist Scott Ingram and counts the city’s most recognisable artists as members, like Meko (currently rumoured to be in a representation bidding war between two New York galleries), Hasani Sahlehe (a 2022 Artadia finalist) and William Downs (represented by Derek Eller Gallery in New York). “There’s a supportive artist community [here] that’s quite different than places that are a level-up in competitiveness,” says Erin Jane Nelson, an artist and the artistic director of Burnaway.

“There are many ways to be an artist in Atlanta,” says Andrew Westover, the High Museum’s director of education. The opportunities for creative day jobs are varied, from working in the entertainment industry on film and television to teaching at one of the city’s many schools, from Georgia State University and Spelman College to the local campus of the Savannah College of Art and Design.

Growing pains

Even as Atlanta offers both space and structure to be a practicing artist, those looking to establish themselves at the national level and beyond are often lured away. “There’s no sustainable model for saying ‘I want to stay here’,” says curator, writer and former Atlantan TK Smith, now a curator at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

While many members of Atlanta’s art community reject “New York” (a metonym for the art market), they will also reluctantly acknowledge that without New York, something isn’t clicking. Some locals have explained this in part by claiming that, for a long-time, many Atlanta galleries worked outside of the art market.

Installation view of Emmanuel Massillon: Some Believe It To Be Conspiracy at UTA Artist Space in Atlanta Photo by Mike Jensen

Veterans of the scene say that galleries operating in the city traditionally charged collectors blue-chip prices—$90,000 for a decorative abstract painting by a relative unknown, $200,000 for a lesser Thomas Hart Benton work on paper—and kept their clients largely in the dark about how deals were made and artists’ careers managed in New York and Los Angeles. Meanwhile, artists who moved to New York, most notably Todd Murphy, were encountering issues with price disparity between their galleries in Atlanta and elsewhere. How could similarly-sized primary-market paintings from the same series simultaneously be offered for $25,000 in New York and $80,000 in Atlanta?

Further complicating the picture are the interior designers. In speaking to collectors, advisers and gallerists in the city, nearly everyone brought up “the designers”, without wanting to be quoted saying anything critical. “It’s been difficult to build great contemporary art collections down here because the decorators call the shots,” one adviser said, speaking candidly on condition of anonymity. “The attitude of ‘does it match the couch’ prevails.” Many local interior designers have exclusive dealings with specific galleries and take a percentage on works sold.

The power brokers in Atlanta’s art world point to these two dynamics—the lack of a support structure for artists at a mid-career stage and beyond, and the interior designers pulling all the strings behind the scenes—as the factors that have held the city back. But there is innovation afoot, both from outside forces moving in and homegrown forces growing up.

So far, the much-hyped United Talent Agency (UTA) Fine Arts gallery has not served as the city’s art angel. The arrival of the Hollywood talent agency’s fine arts division in Atlanta early this year prompted The New York Times to ask: “Can a Global Talent Agency Make Atlanta an Art Destination?” Neither immediately nor single-handedly, seems to be the answer. “Some openings only have like 20 people”, says gallery sales director Tony Parker. Meanwhile, UTA Fine Arts’ New York pop-up with TikTok sensation Devon Rodriguez drew crowds of thousands, plus dozens of New York Police Department officers to assist with crowd control.

Rather, change in the Atlanta art scene is happening in a more bottom-up, bootstrapped fashion. Bombeck, guided by the mantra “buy what you love but know what you’re buying”, has filled her Buckhead home with works by Atlanta artists including Meko, Downs and Murphy, as well as Liliana Porter, Tania Candiani and Corydon Cowansage, “to show Atlanta how to collect. I’m helping to expose people to the greater pieces of the whole and bringing down the barrier to entry or intimidation factor,” she says. She helps collectors “to start”, she says, including Kathryn and Joe Cottone and FirstView Financial chief executive Cherie Fuzzell. Once these collectors are on their way, she hands them off to people she calls “real advisers”, such as Atlanta-based Rebecca Dimling Cochran.

Benjamin Deaton, the director of Wolfgang Gallery—which represents artists including Alic Brock, Jay Miriam-White and Zachari Logan—says he started the gallery with Anna Scott King Masten “to bring what we thought some of the best contemporary art regardless of being in the region”. Wolfgang, named for Deaton’s son, opened in September 2022. “We are not a blue-chip gallery—we don’t want to be—but we have 4,000 sq. ft. For these artists in major metropolitan cities, the galleries they are showing in are a fraction of that, so we can offer space and a much broader audience,” he says.

The back gallery at Wolfgang Gallery, featuring works by Jay Miriam Courtesy Wolfgang Gallery

Masten adds, “We’re doing this to bring great art to Atlanta, but there’s this big disconnect about contemporary art in Atlanta. People think it’s elitist and exclusive, and we can make people feel more comfortable, like ‘we can make you a collector’.” Even so, they say, the gallery took some time to find its footing. “I don’t think we anticipated people’s need to classify what type of gallery we were,” Masten says. “In the first six months, maybe one person from Atlanta was buying. Now it’s changing. Our last show [of works by Lloyd Benjamin], 70% were buyers from Atlanta.”

“We’re really committed to helping Atlanta grow in collecting,” says Anna Walker Skillman, director of photography-focused Jackson Fine Art, which for 20 years has participated in global fairs from Paris Photo to this year’s debut of Photofairs New York, as well as being an early adopter of online platforms like Artsy that helped it expand its collector base. Walker Skillman helped build Elton John’s storied photo collection (long housed in the celebrity-heavy Park Place building in Buckhead) as well as those of quite a few Atlanta’s most famous Black celebrities, including Usher. She also helped put the artists Todd Murphy, Sheila Pree Bright and Shanequa Gay on the contemporary art map.

Installation view of Jackson Fine Art gallery in Atlanta Photo by Charlie McCullers

“You’re dealing with a city where art is not the focus, and so there are so many different types of clients in Atlanta,” Walker Skillman says. “There’s so much energy and interest,” she adds, but “it takes time and educating that person who wants to buy something”.

The framing of that exposure and education, however, is still a work in progress. Will standards of taste and knowledge be imported from New York and other art world capitals, or home-grown?

“This gallery has survived for 34 years without the recognition of New York and all these other places,” Johnson says. “There must be something here that is of value to people. To say that it’s not good enough, or that it’s negative in a way is saying that what you want is every artist do the same thing in different places, so that you can go visit the same thing in different places. It’s a coloniser way of thinking. Are we going to make Atlanta the next commodity?”