How many years have I been shouting about the Trilateral Commission from rooftops to mostly deaf ears? Since 1977. Forty-eight years! Wake up, world! Your soon and coming demise is upon you as your ears remain plugged. ⁃ Patrick Wood, Editor

A “scientific priesthood” will determine the limits of our actions and “protect” us from complex global shocks.

There are barely two months left until the big UN meeting Summit of the Future (September 22-23) where the “Pact for the Future” is to be signed by world leaders (heads of government and state). The pact, which essentially constitutes a blueprint for a global technocracy to manage global risks on behalf of the global corporatocracy, is now being finalised for completion by early August.

The preparatory work began in 2015 with the report Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance by The Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance.

The commission, which was chaired by former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Nigerian UN diplomat Ibrahim Gambari, recommended that a World Conference on Global Institutions be held when the UN celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2020. The aim was to reform the UN system to make it better equipped to respond effectively on “new threats and opportunities”. At the same time, work began on developing “global governance innovations”.

The commission was supported by the Dutch institute The Hague Institute for Global Justice and the Washington-based think tank Stimson Center.

Stimson, who has been extremely central in the preparatory work, represents the global corporatocracy (WEF, CFR) and international philanthropy (Carnegie, Rockefeller, Ford, Gates, etc.). The pact is part of their ongoing world conquest.

Madeleine Albright, a protégé of Columbia professor Zbigniew Brzezinski (co-founder of the Trilateral Commission with David Rockefeller), was an ideal choice. As a member of TriCom as well as the Council on Foreign Relations, there was no doubt what interests she served.

Corporate members (gold level) of Council on Foreign Relations

Five years later, in the middle of a pandemic that was designed to act as a “triggering event”, the UN organization’s future priorities were discussed at the UN meeting “Building the Future We Want, The UN We Need”.

During the meeting, which was arranged in collaboration with the Stimson Center, a number of proposals and projects were also presented on how the future governance would work.

This included the Climate Governance Commission, whose purpose is to (in partnership with, among others, the Stimson Center, the Swedish Global Challenges Foundation, and the ever-present Rockefeller Foundation) “developing, proposing and building partnerships that promote feasible, high impact global governance solutions for urgent and effective climate action…”

One year later, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, on behalf of UN member states, presented the report Our Common Agenda with twelve commitments to reform the UN system in order to quickly implement the sustainability goals.

Subsequently, eleven policy overviews and a report from the UN panel HLAB on Effective Multilateralism have been published as a basis for the process. This panel was also supported by the Stimson Center and the Global Challenges Foundation.

In January, the first draft of the pact was published, followed by negotiations with member states and other stakeholders. The latest revision was published on 17 July.

The pact’s message is that we are in a “global transformation” where a growing number of global catastrophic risks threaten to completely break the world apart (Breakdown).

But progress in science, technology and innovations can instead mean a breakthrough to a “better” and more sustainable world (Breakthrough).

However, this requires that the crises are handled collectively by a multilateral system with the UN at the center. For this purpose, the UN needs to be upgraded.

The two paths of development (Breakdown and Breakthrough) show obvious similarities to the scenarios described by systems philosopher Ervin Laszlo in his book Macroshift: Navigating the Transformation to a Sustainable World from 2001. Laszlo is a futurist with a background in the World Future Society and the Club of Rome, which during the end of the 1970s led the UN project “New International Economic Order”

.

.

The intention is for this new multilateral world system to “protect future generations” and to implement the United Nations’ utopian Agenda 2030 with its seventeen sustainability goals. According to the pact, this can only be realised if carbon dioxide emissions are drastically reduced to keep the temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius. The climate has long been the linchpin of the agenda.

The Pact for the Future contains 58 actions (divided into five chapters) and two annexes (Global Digital Compact and Declaration on Future Generations) to implement the shift to a system that “effectively respond to current and future challenges, in partnership with all stakeholders.”

- The first chapter deals with the fulfilment of the sustainability goals.

- The second chapter deals with promoting the international peace agenda.

- The third chapter is about making use of science, technology and digital collaboration.

- The fourth is about meeting the interests of young people and future generations.

- The fifth and final chapter is about reshaping global governance to be able to handle the challenges of the future.

The pact is sold with the promise that poverty and hunger will be eradicated, that equality will be promoted, that all marginalised groups will be given a voice, that human rights will be respected, that peace will be maintained and that the planet will be saved from destruction. All we have to do is hand over the keys to Spaceship Earth to the planetary stewards!

The document is carefully written to generate broad support and leave room for interpretation. Since the previous draft, however, the wording “we agree on” has been changed to a more ominous “we decide that”.

When examining all the impenetrable clauses, where few concrete guidelines are given on how the measures should actually be enforced, the contours of the system that is ultimately intended to be implemented nevertheless emerge. This shows itself most clearly in the concluding chapter and in the appendices. But it can also be found in the extensive background material.

In specific terms, it is about the establishment of a technocratic rule of experts, where a “scientific” priesthood will determine the limits for our actions and “protect us” from global shocks. Science will be used more frequently to anchor decisions.

But it is all based on a “science” that is not allowed to be questioned or scrutinised. Instead, it constitutes an absolute truth. It is “The Science”, science as a dogma, rather than a method.

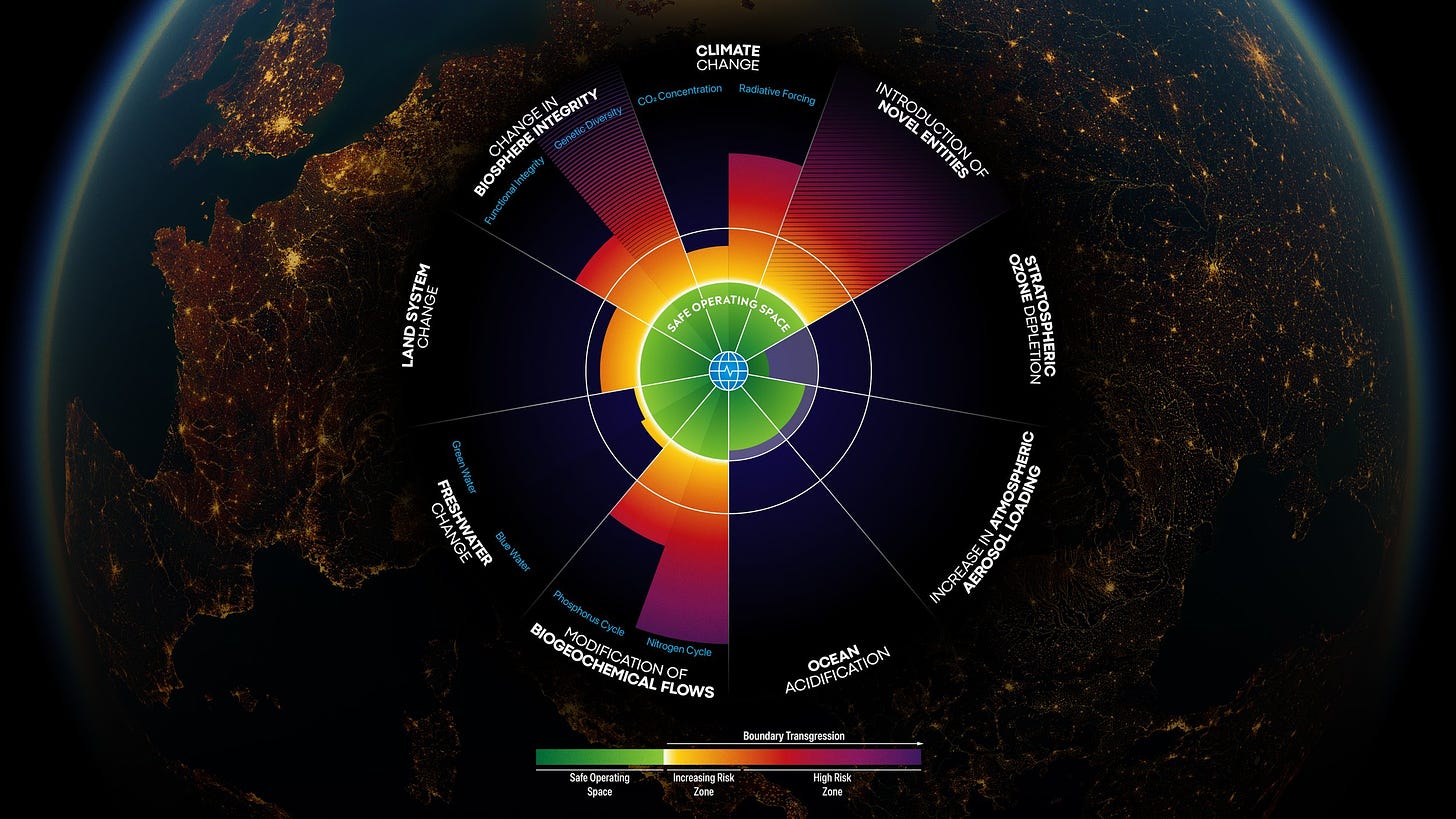

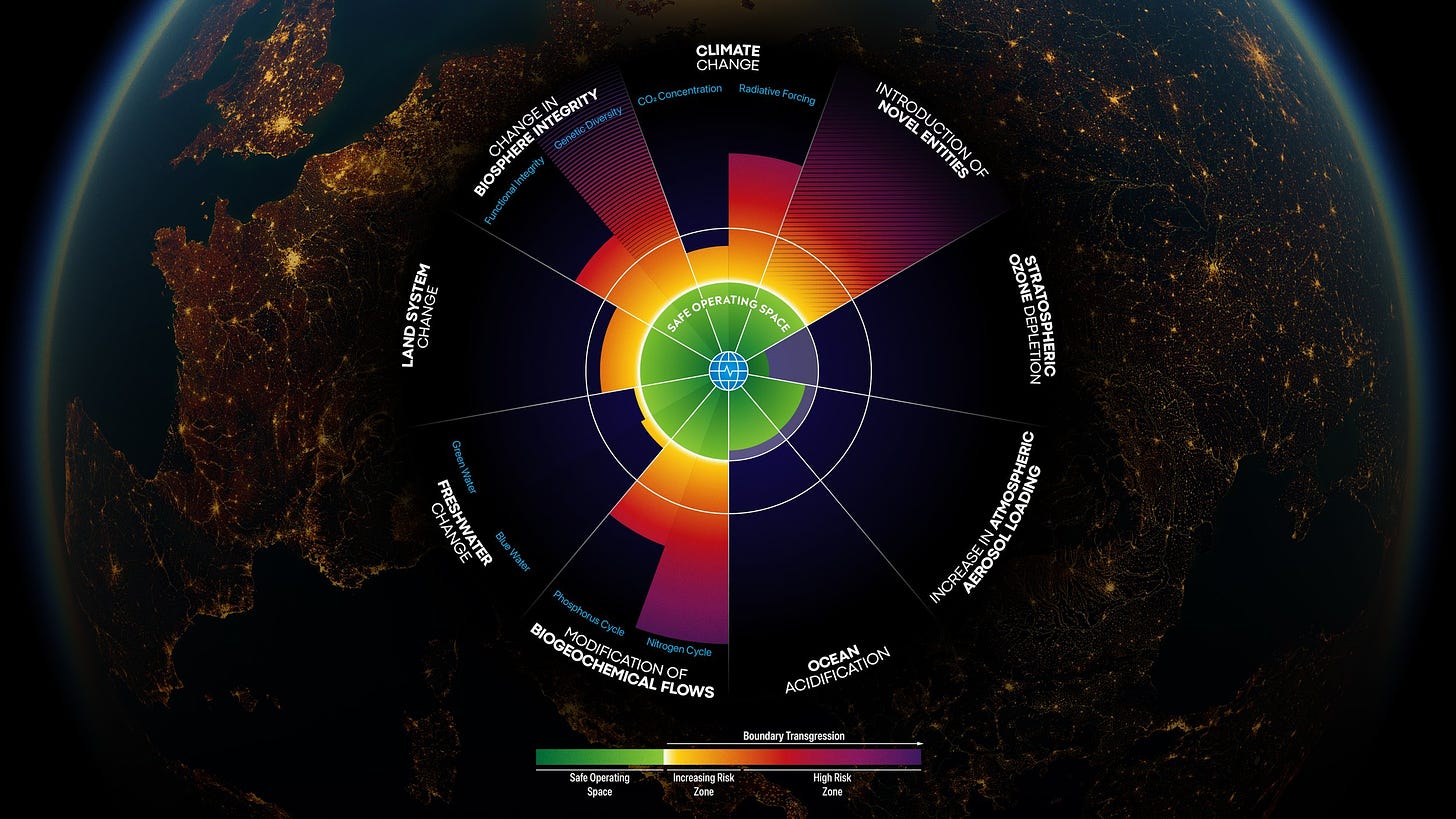

This is where researchers such as Potsdam Institute director Johan Rockström and his framework on the planetary boundaries comes in. According to his team of loyal scientists, humanity has already crossed six of these nine boundaries and therefore needs a firm hand to be guided in the right direction. Rockström has had a great influence as an adviser during the policy process through his co-chairmanship of The Climate Governance Commission.

The UN Secretary-General has already created a scientific council consisting of seven “eminent scientists” as well as a group of chief scientists from UN agencies including “pandemic expert” Jeremy Farrar, since 2023 chief scientist at the WHO, and climate scientist Jürg Luterbacher from the WMO.

Farrar had a prominent role during the C-19 pandemic as director of the Wellcome Trust (established in 1936 by pharmaceutical magnate Henry Wellcome, founder of Burroughs Wellcome, one of the predecessors of GlaxoSmithKline). Farrar was recently labeled “pandemic protector” on Time Magazine’s list of Health Titans.

Luterbacher on the other hand has participated in an article about how the AI program Climinator (!) can be used to automate fact-checking of claims about climate change.

According to the Declaration for Future Generations, “current generations must act with responsibility to safeguard the needs and interests of future generations”. These interests include “urgent climate action”, responding to demographic trends and strengthening health systems with “equitable” access to vaccines and other health products.

In other words, our lives are in need of global dictates so as not to endanger the generations yet to be born.

According to the declaration, the voice of future generations will be represented by an “envoy for future generations”, while the measures to protect the future are proposed to be evaluated by a high-level meeting every five years.

This has been a stumbling block in the negotiations. In the original proposal, there was a desire to create a Forum for Future Generations that would take place in the now-defunct Trusteeship Council. The Stimson Center suggested in its report Road to 2023: Our Common Agenda and the Pact for the Future that:

The international community should repurpose the United Nations’ all-but-defunct Trusteeship Council to exercise a new, carefully shaped role as a steward of the Global Commons, with a view to enhancing intergenerational equity and the well-being of future generations.

However, this met with resistance. According to the Stimson Center, because some member states have different ideas about what can be classified as global commons and because the forum’s location in the Trusteeship Council gives associations to a colonial past.

However, it can be stated that these ambitions have not been dropped and will most likely resurface on the negotiating table after the pact is signed. For example, the United Nations University Center for Policy Research, the Potsdam Institute and the Global Challenges Foundation (with Johan Rockström on the board of directors) have recently proposed a global governing body that will oversee all of the planet’s life-sustaining systems, the “Planetary Commons” (air, water, soil, biosphere and ice)!

Who will sit on such a body and which envoy will represent people who have not yet been born is yet to be decided.

However, the Climate Governance Commission, in its report Governing the Planetary Emergency, has suggested that: “key, powerful actors take adequate responsibility and act in service of the shared interests of all of humanity, life on Earth, and future generations.”

The Trusteeship Council during the ID2020 Summit in 2018

Rockström and his co-authors propose, with a reference to Stimson Center, that this body should be placed in the Trusteeship Council. But the proposal is older and was already included in the Trilateral Commission’s 1991 report Beyond Interdependence: Meshing the World’s Economy and the Earth’s Ecology.

TriCom is a central node in the global corporatocracy which has both planned the “pact” and which has intended to assume the role of “stewards” of the planet.

As stated in the Davos Manifesto (for business leaders) from the World Economic Forum: “Management must serve society. It must assume the role of a steward of the material universe for future generations.”

The new system is based on “anticipatory planning” where a massive data collection and monitoring of both people and earth systems will be used to support decision-making and crisis management. The details of this are regulated in the Global Digital Compact.

This means that pretty much the entire world’s population must be connected to the internet and that “reliable” AI systems will be developed to accelerate the fulfilment of the sustainability goals.

The digital transformation will be carried out in partnership with international financial institutions, the private sector, academia, the technical community, and civil society. Of course, this means, just like during the “pandemic”, business opportunities for the big tech giants.

The pact also provides support for upgrading the UN to “UN 2.0”.

This concerns how the data collection is to be used by the UN to help member states enforce the changes deemed necessary. This work has already begun through the launch of the UN Futures Lab and UN 2.0: Quintet of Change. Through various techniques (such as nudging and sludging), we will be persuaded to make the “right choices” in order to avoid “doom” and instead create ” a better world”.

It is clear that the futurists’ thinking about long-term planning and foresight has taken over the UN. It is the World Economic Forum’s “Fourth Industrial Revolution” that will solve the world’s problems. What we are witnessing is the birth of the global technological society that the utopians of the World Future Society dreamed of in the 1970s. As described on their website:

Covid-19 is the first time in our species existence where we at a global scale are experiencing a potential systems collapse of our Civilization. We now have the opportunity to create a Civilization Type One which can better handle exponential growth and human advancement.

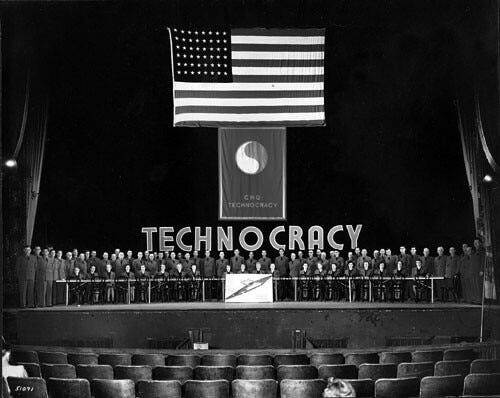

But is also grounded in the longtermism view that it is a key moral priority to influence future events in order to avoid extreme existential risks. An idea that was pioneered by Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom. However, the roots can be traced even further back to sci-fi authors such as H.G. Wells and the technocrats with the grey uniforms in Technocracy Inc (the history of which Patrick Wood has documented in detail in his books and articles).

In 1932, Wells coined the term “Foresight”, which refers to “the ability to predict what will happen or what is needed in the future”.

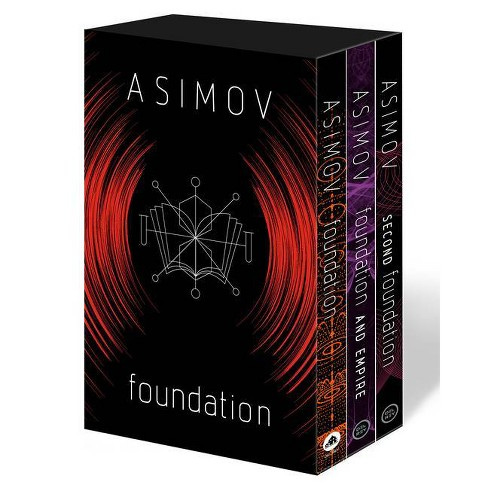

This thinking is also associated with sci-fi author and futurist Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy from 1951–53, where the application of the fictional science of “psychohistory” was used to predict future events.

One of the most important actions in the pact is “Strengthening the international response to complex global shocks”. This refers to events that have “severely disruptive and adverse consequences for a significant proportion of countries and the global population.”

The Secretary-General is therefore asked to develop “protocols for convening and operationalising emergency platforms based on flexible approaches to respond to a range of different complex global shocks.”

However, consideration must be given to “national ownership and consent, justice, solidarity and partnership”. In practice, this means that member states will be responsible for implementing any measures on their own territory. The platform is not meant to be permanent, but according to the Emergency Platform policy overview, the assignment can be extended if deemed necessary.

At the same time, just as during the pandemic, the crises create opportunities for the multi-actor networks that will be convened to deal with the current “shock”. This will undoubtedly take place in close cooperation with the UN’s strategic partner World Economic Forum and the global corporations.

As WEF Executive Director Börge Brende told António Guterres in Davos in January: “We are also very much looking forward to your Summit of the Future in September, and you can count on us and our full support”.

Once the protocols are in place, it probably won’t be too long before the world is faced with a new complex global shock.

The Climate Governance Commission has called on the United Nations to declare a planetary emergency in connection with the Summit of the Future. This would lead to the convening of an emergency platform and the implementation of a planetary emergency plan. In the background, all the necessary preparations have already been arranged. One example is Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisor’s project Global Commons Alliance, where Rockström once again appears in a leading role.

But it seems unlikely that they would get enough support for a declaration of a planetary emergency already in September.

But there are a number of other imminent global crises looming on the horizon that a new US presidential administration and the newly appointed European Commission likely will face.

In the accompanying policy overview, seven conceivable complex shocks are listed. It undeniably gives associations to the Book of Revelation and can conceivably be connected with a possible global financial crash and a corresponding world war. The big event that Whitney Webb and others have warned about and that has been discussed by UN’s advisers from the Climate Governance Commission.

These crises are in my opinion meant to be the trigger (Breakdown) that will lead us into the new system (Breakthrough) where a global governing body takes its seat in the Trusteeship Council to oversee the life support systems (the ecology) and a “global apex body” oversees the world economy.

As the futurist John Platt wrote in 1975 in connection with the World Future Society’s conference “The Next 25 Years: Crises and Opportunities”:

These crises, fearful as they are, also offer the possibility of being stepping stones to improved methods of global organization and management for the prosperity of everybody.

Everything will be made possible with the help of massive data collection and digital monitoring. This is the society that TriCom co-founder Zbigniew Brzezinski envisioned back in 1968:

Power will gravitate into those who control information and can correlate it most rapidly. Our existing postcrisis management institutions will probably be supplemented by precrisis management institutions, the task of which will be to identify in advance likely social crisis and to develop programs to cope with them. This could encourage tendencies during the next several decades toward a technocratic dictatorship, leaving less and less room for political procedures as we now know them.

In any case, that is the future that the global corporatocracy desires. But we are not there yet and a lot can happen along the way.

I will conclude with my presentation at the Summer Emergency Broadcast Summit where I talked about the background to the Pact for the Future.

Footnotes:

Read full story here…