The fiduciary role has entered a new era. Complexity defines every decision, and specialization is no longer optional. Modern trust administration demands more than technical proficiency. It requires strategic insight, fluency in tax law and a stewardship mindset that balances optimization with long-term family goals. To succeed in 2026 and beyond, fiduciaries must elevate their expertise across five critical dimensions.

Income Tax Planning

A year ago, uncertainty surrounded the sunset of key provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Today, following the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (the OBBBA)1 on July 4, 2025, trustees have clarity and a renewed urgency to assess how these tax changes affect existing trusts and future trust design. For the first time since the Bush-era tax cuts, taxpayers can plan with confidence that major provisions will remain stable absent future legislation.

The OBBBA significantly reshaped the tax landscape. The estate and gift tax exemption increased to $15 million per individual and $30 million per couple, indexed for inflation beginning in 2027. This creates new lifetime gifting opportunities. Yet the real pivot for 2026 and beyond is toward income tax planning. New deductions and limitations hinge on adjusted gross income (AGI), making timing, character and taxpayer identity, whether individual, married or non-grantor trust, critical levers for optimization.

This shift coincides with a market surge. The S&P 500 has appreciated over 17% year-to-date as of early December 2025.2 Many trusts now hold highly appreciated, low basis assets. Trustees must educate beneficiaries that realizing gains, though triggering tax in a measured approach, is often the prudent path to diversification and risk reduction. Concentrated positions amplify volatility. Selling and reallocating can strengthen long-term outcomes.

Action points for trustees include:

• Evaluate whether to turn off grantor trust powers. Moving to non-grantor status can keep taxable income off the grantor’s return, helping avoid the top 37% bracket and mitigating the haircut effect on itemized deductions for the grantor. Non-grantor trusts aren’t subject to the charitable floor, which under the OBBBA is the 0.5% minimum of AGI that individuals must meet to claim charitable deductions.

• Weigh key factors before making this change. Consider the potential permanent loss of the ability to reduce a grantor’s taxable estate by paying the trust’s income tax liability, as well as the inability to engage in tax-free sales to the trust in the future. In addition, evaluate the total tax liability for the trust, the beneficiary and the grantor. Often, a switch from grantor to non-grantor trust status results in higher taxes for beneficiaries receiving distributions.

• Plan transactions before altering trust status. For example, exercise a substitution power to remove low basis assets in exchange for high basis assets prior to turning off grantor trust powers.

• Consider fiduciary implications before restructuring. Changing trust status and altering tax liability may affect beneficiaries’ expectations. Trustees must document their rationale, ensure transparency and confirm compliance with the duty of loyalty and prudence.

• Coordinate timing of income recognition and deductions. Leverage new AGI-based provisions. For families near deduction phaseouts, strategies such as gifting property to non-grantor trusts or exploring pass-through entity tax workarounds may reduce the aggregate income tax burden.

• Model the impact of diversification. If selling low basis assets to reduce concentration, use modeling to show beneficiaries how concentrated positions increase volatility without offering higher expected returns compared to a diversified portfolio. This is often called “uncompensated risk,” meaning the owner bears the risk of poor performance without any additional expected return.

The OBBBA offers stability, but complexity remains. Trustees who act now, balancing tax efficiency, diversification and fiduciary duty, will position families for resilience in a transformed tax environment.

Structural Flexibility

Beyond tax planning, trustees must also address structural flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances. Trustees are seeing an increase in requests to change the terms of trusts. This rise stems from two factors. First, many trusts were designed to last a very long time, meaning the original rules are now playing out in a modern world where beneficiaries often have different ideas about how assets and distributions should be managed. Moreover, grantors might have had the trust drafted differently had they been aware of the future circumstances that ultimately came to exist. Second, the law has created new, powerful ways to make these changes outside of court, such as non-judicial settlement agreements and decanting. These tools provide beneficiaries with additional avenues to pursue modifications.

This combination of longevity and flexibility puts the trustee in a continuous, complex balancing act. The central problem is choosing between making current beneficiaries happy and upholding the settlor’s original purpose. The trustee’s job is to protect the reason the grantor created the trust in the first place, even if that means saying no to a beneficiary request. In designing a trust, the draftsperson should consider documenting grantor intent, as this isn’t always evident on the face of the instrument, especially one in which ascertainable standards and commonly used provisions are included. A statement of wealth transfer intent can provide trustees with valuable insight into the trust’s purpose.

When a trustee reviews a request for modification, they must be extremely careful. Even seemingly small administrative changes can impact what the grantor intended. For example, a trustee at Northern Trust recently used decanting powers to update investment powers in a 1980s trust, aligning them with environmental, social and governance (ESG) priorities without requiring court intervention. The trustee must be confident and document the reasoning that incorporating ESG factors doesn’t harm the beneficiary’s financial interests or is expressly permitted by the settlor’s intent or a purpose a court would approve.

Action points for trustees include:

• Document grantor intent clearly. Encourage grantors to include a statement of purpose or a non-binding letter outlining their goals for the trust.

• Evaluate modification requests carefully. Even minor administrative changes can alter the trust’s purpose. Use legal tools like decanting or settlement agreements only after confirming alignment with grantor intent.

• Balance competing interests. When beneficiaries request changes, weigh their preferences against the settlor’s original objectives. Uphold the trust’s purpose even if it means denying certain requests.

• Maintain transparency. Record the rationale for decisions, especially when using discretionary powers or modern tools like ESG investment updates.

Grantors creating trusts today should be explicit about which elements are truly non-negotiable. This clarity provides trustees with the legal certainty needed to manage these conflicts across generations. A trust design needn’t include an absolute ban on modification or total limit on decanting, but some limitation may be prudent to ensure the grantor’s purpose is fulfilled. Including a statement of intent or an accompanying non-legally binding letter from the grantor to the trustee, describing the purpose and intent behind establishing and funding the specific trust, can provide invaluable guidance.

Beneficiary Well-Being

Beyond structural changes, trustees are rethinking the very purpose of trusts to support holistic well-being. Historically, a trustee’s primary duty was the strict preservation and financial growth of the trust’s capital. Today, many grantors establish trusts not just to manage money but also to actively support a beneficiary’s life success, including educational goals, mental health and overall quality of life.

New state statutes recognizing well-being trusts address this modern reality. Delaware recently passed a well-being statute,3 allowing a trustee with discretionary power to give weight to the beneficiary’s overall well-being and circumstances as the trustee deems appropriate. Within this framework, the trustee may consider factors that extend beyond a beneficiary’s financial needs. Thus, a trustee isn’t only considering whether a beneficiary needs the funds but also what a distribution might accomplish for the beneficiary.

Many factors go into this assessment: spending patterns, age, maturity, physical and mental health, substance abuse issues, personal growth and development and whether it will support constructive goals or potentially harmful behavior. Trustees are challenged to weigh questions like whether withholding a distribution might motivate positive behavior or what would best serve the beneficiary’s interests five or 10 years from now.

These laws can validate a grantor’s intent to prioritize human capital over purely financial returns. By making the support of subjective factors a legitimate trust purpose, these laws offer fiduciaries clearer guidance. They confirm that trustees can confidently make complex discretionary distributions without fear of liability from future beneficiaries who might otherwise claim a breach of the traditional duty of prudence.

Consider a trust funding therapy and career coaching for a beneficiary recovering from a health crisis, an approach now validated under these statutes. In contrast, the laws provide trustees the ability to deny distributions when the trustee deems such distribution won’t help the beneficiary’s development, even when demonstrated financial need exists.

This shift introduces operational challenges. Monitoring and reporting on a beneficiary’s emotional state or career development requires detailed qualitative work, unlike measuring stock returns. Trustees often engage specialized consultants, such as coaches, educational advisors or therapists, to fulfill this expanded mandate. These tasks increase administrative costs, raising concerns about the justification of fees.

Trustees must maintain an unwavering duty of loyalty, ensuring expenses remain reasonable and proportional to the value delivered. Success depends on striking a balance between flexible purpose and transparency. Trustees effectively administering a well-being trust will explain their reasoning to beneficiaries where appropriate. They’ll document decisions and use consistent standards and processes in doing so. Trustees of well-being trusts need to show they’re acting in the beneficiary’s interest, aren’t acting arbitrarily and are open to changing circumstances.

Action points for trustees include:

• Adopt clear standards. Define what well-being means in the context of the trust, and apply consistent criteria for discretionary distributions.

• Engage experts when needed. Use educational advisors, therapists or coaches to support decisions, but ensure costs remain reasonable and proportional.

• Document everything. Keep detailed records of assessments, decisions and outcomes to demonstrate fiduciary prudence and avoid liability.

• Communicate thoughtfully. Explain decisions to beneficiaries when appropriate to reduce misunderstandings and maintain trust.

• Monitor evolving laws. Stay informed about statutes like Delaware’s well-being trust provisions to ensure compliance and leverage new flexibility.

Administering a well-being trust presents unique challenges. The trustee’s assessment of a beneficiary’s well-being can appear subjective. Relationships with beneficiaries can come under pressure as they likely won’t welcome perceived judgment on life choices or interests, especially when requests for distribution are withheld or delayed. Trustees bear the responsibility of documenting both the decisions and the process and outcomes.

Specialty Assets

While trust purpose is evolving, investment strategy is equally critical in meeting fiduciary obligations. The modern investment landscape compels trustees to evolve their approach to portfolio diversification. The prudent investor rule has come a long way since the 1830 Massachusetts case Harvard College v. Armoy,4 which established the prudent man rule. That standard focused on evaluating each investment in isolation as opposed to the modern prudent investor rule originally adopted in the Third Restatement of Trusts in 1992.5 The modern rule, which has continued to evolve since its enactment, is portfolio-based, requiring trustees to consider each investment’s role in an overall portfolio. It mandates diversification and considerations of risk-return tradeoffs for the beneficiaries. It doesn’t include prohibitions on specific investments.

In the past, conservative trustees prioritized the liquidity and low volatility of public markets, believing that the illiquidity and high fees of private investments made it imprudent for a trustee’s primary duty of capital preservation. However, significant returns that often exceed market averages are increasingly found in private markets.

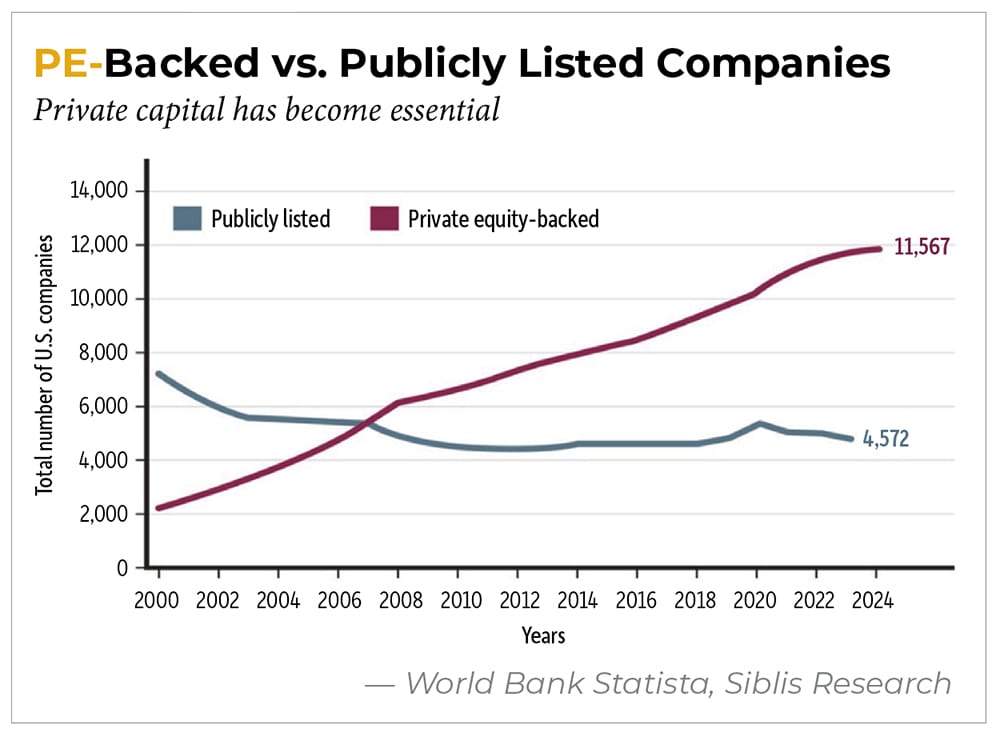

Public markets no longer represent the full economic universe. Between 2000 and 2024, the number of U.S. publicly listed companies on NYSE/NASDAQ fell from approximately 7,000 to 4,572, while the count of private equity-backed companies (excluding venture capital) surged from about 2,000 to 11,567.6 With over 85% of companies remaining private longer, private capital isn’t merely an alternative; it’s essential. See “PE-Backed vs. Publicly Listed Companies,” below.

Private companies can take a long-term focus on value creation without the pressure of quarterly earnings, market volatility and daily price fluctuations affecting decision making. In some cases, private equity (PE) investors can take a more active role in the company’s operation and strategy by sitting on the board, providing strategic guidance and accessing investor networks and resources. Private companies buoy portfolio diversification due to having different drivers of returns, avoiding daily market sentiment and providing exposure to different stages of company development and access to underrepresented sectors.

To satisfy the duty of prudence, trustees must bridge the gap when selecting investment solutions and beneficiaries’ distribution needs while also ensuring beneficiaries understand the strategy. For example, a trustee allocating 10% of a $50 million trust to PE must explain illiquidity and valuation timing to beneficiaries accustomed to daily pricing.

Action points for trustees include:

• Explain illiquidity and time horizon. Clarify that private investments often require long holding periods, sometimes a decade or more, and confirm that these align with the trust’s objectives and liquidity needs.

• Demystify valuation and reporting. Educate beneficiaries on how private holdings are valued, emphasizing that pricing is periodic and lagged rather than daily. Provide clear schedules and expectations for reporting.

• Ensure competence and transparency. Vet fund managers rigorously, justify fees and document the rationale for including private investments as part of prudent diversification. Communicate these decisions openly to maintain confidence.

Transparency remains essential for fulfilling fiduciary duties and sustaining beneficiary trust.

AI Integration

Finally, technology is redefining fiduciary practice, introducing both opportunities and ethical challenges. Artificial intelligence is reshaping trust administration. It’s no longer limited to simple automation. AI can forecast wealth, optimize tax strategies, review documents, extract key trust provisions and track critical deadlines such as tax filings and distribution schedules. It’s also being used to monitor compliance with changing state and federal regulations and to flag potential deviations. These examples represent only the beginning of what’s possible.

Trustees must understand both the advantages and the limitations of these tools, as emphasized in Comment 8 to Rule 1.1 of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct.7 Every AI-generated outcome needs human validation. Blind reliance can lead to breaches of fiduciary duty. Consider a scenario in which an algorithm recommends denying a discretionary distribution based on an internal risk score. If the trustee accepts that recommendation without understanding the reasoning, they face a “black box” problem. They can’t explain the decision or demonstrate a prudent basis for it.

Data security and privacy risks add further complexity. Even when information is anonymized, AI can sometimes combine details and identify wealthy clients. Ownership of unique assets, such as a professional sports team, combined with geographic location, public filings and philanthropic affiliations can make re-identification easier. Trustees must therefore ensure that platforms provide strong contractual protections and maintain confidentiality at all times.8

Action points for trustees include:

• Verify every output. Don’t assume AI is correct. Require staff to cross-check all recommendations against governing documents and applicable law. Build a review protocol that requires every AI-generated analysis or scoring to be validated by a qualified professional at the source before taking action.

• Use secure platforms only. Direct employees to avoid public or consumer-grade AI tools. Mandate enterprise-level platforms with contractual data protection clauses. Confirm vendors meet cybersecurity standards, and conduct regular audits of data handling practices.

• Keep humans in control. Assign responsibility for ethical oversight to a designated compliance officer or senior trustee. Require human judgment on all discretionary decisions. Train staff to recognize algorithmic bias and document the rationale for every decision influenced by AI.

• Govern, train, disclose. Create written governance policies for AI use. Include clear escalation paths for errors or anomalies. Provide ongoing training for trustees and support teams on AI risks and fiduciary duties. Disclose AI usage in engagement letters so clients understand how technology supports, but doesn’t replace, human decision making.

When managed properly, AI can save time and improve outcomes. Yet it can’t replicate empathy, judgment or mediation, which remain central to the trustee’s role. For this reason, AI should be used to enhance performance and never to replace the human expression of fiduciary responsibility.

Fiduciary Excellence

In 2026, fiduciary excellence is defined by the ability to steward complexity with clarity. Whether navigating income tax strategy, structuring trusts for flexibility or supporting beneficiary well-being, fiduciaries must bring a depth of expertise that matches the sophistication of the families they serve. The trust landscape may be evolving, but the core challenge remains: to steward wealth with wisdom, integrity and foresight.

Endnotes

1. One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Pub. L. No. 119-21, 139 Stat. 72 (July 4, 2025).

2. Slickcharts, “S&P 500 Year to Date Return for 2025,” www.slickcharts.com/sp500/returns/ytd (accessed Dec. 2, 2025).

3. Del. Code Ann. tit. 12, Section 3345 (2024).

4. Harvard College v. Amory, 26 Mass. (9 Pick.) 446 (1830).

5. Restatement (Third) of Trusts Section 90 (Am. L. Inst. 2007).

6. World Bank (2024), Listed domestic companies, total (United States) [Data set], World Development Indicators, https://data.worldbank.org; “The public to private equity pivot continues,” Citizens Bank (December 2024), www.citizensbank.com/corporate-finance/insights/private-equity-trends.aspx.

7. American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.1 cmt. 8 (2024).

8. Gerry W. Beyer, “Don’t Byte Off More Than You Can Chew: Ethical Considerations for the Estate Planner in the World of Generative Artificial Intelligence,” 15 St. Mary’s J. on Legal Malpractice & Ethics 32 (2025).