Five years after the Implant Files investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, advocates in the U.S., Canada and India are urging health regulators to do more to protect patient safety as faulty dental implants, surgical staplers, respirators and other medical devices continue to injure patients.

The Implant Files, published in November 2018 by ICIJ in collaboration with 58 media partners worldwide, exposed the flaws of the global medical device industry and documented how regulators around the world had approved devices with little or no safety testing.

Millions of people’s lives have been saved, extended or made better by implanted medical devices. But the Implant Files analysis found more than 1.7 million injuries and nearly 83,000 deaths that were suspected of being linked to medical devices over a 10-year period in the U.S. alone.

Reporters interviewed patients, doctors and industry insiders in 36 countries whose lives were forever changed after receiving flawed or malfunctioning medical devices, including children with defective insulin pumps.

In the following months and years, the investigation prompted the German health ministry to create a registry for medical devices after considering “how the existing system of approval and monitoring of medical devices can be improved.”

Elsewhere, Australia banned 25 models of so-called textured breast implants due to their association with elevated risks of a rare cancer of the immune system. The U.K. banned spinal implants tested on corpses and pigs and implanted in children with curved spines. India beefed up its medical device regulation expanding the list of devices to be regulated as strictly as drugs. And Canadian health regulators are considering setting up the country’s first breast implant registry to track potentially faulty devices and associated injuries.

In countries such as the U.S., the investigation helped give “breath” to patient advocate movements and make the voices of women injured by breast implants heard by regulators, said Julie Elliott, a Canadian patient herself who later became an advocate and a nurse.

In 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommended breast implant manufacturers use a “black-box warning” to alert patients that the implants are associated with a rare form of cancer.

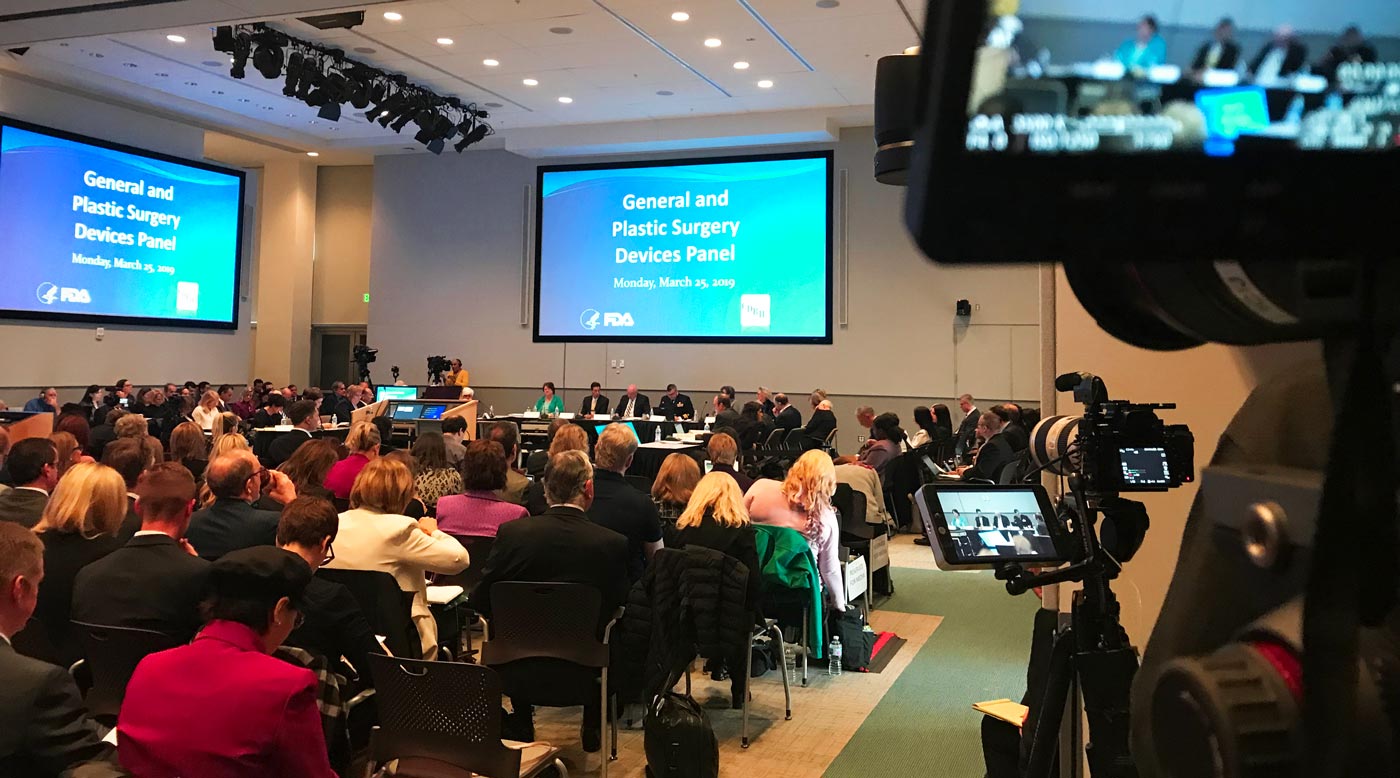

“The FDA got in hot water and decided to have hearings following the ICIJ investigation,” Elliott said. “Then we went to those hearings and it really gave us a big push to work more closely with the FDA. And we’re changing things slowly.”

Going one step further, U.S. legislators introduced a bill in September called the Medical Device Recall Improvement Act, that would mandate the creation of an electronic system to track recalled devices and quickly notify affected patients about the risks.

Madris Kinard, a former FDA public health analyst and medical device surveillance expert, said the proposed law is “encouraging,” because it would also require all healthcare providers, including physicians’ offices and clinics, to report so-called “adverse events.”

Kinard is the founder of Device Events, a firm that analyzes adverse events to help patients and doctors track risky medical devices. She said the global COVID-19 pandemic and scandals involving faulty test kits, masks and other life-saving equipment made the government’s ability to track malfunctioning devices and identify unauthorized products even more urgent.

After pushing the FDA to release more data, Kinard expects the agency to soon publish information on the gender and demographics of the patients who experienced incidents caused by the medical devices ー a small win for patient advocates, she said.

“I had tears in my eyes when they said they were going to do it,” Kinard told ICIJ. She added that having information on patients’ sex and ethnicity is crucial to understand, for example, whether some devices perform worse in children, people of color or women, giving healthcare providers and patients the option to choose alternative therapy.

In 2018, ICIJ’s data journalists and a team of computer scientists at Stanford University used artificial intelligence to develop an algorithm that predicted the sex of patients who had been injured or died because of faulty devices. Their analysis identified 67% of the patients as women and 33% as men. Further reporting by ICIJ and partners in Australia, Italy and other countries confirmed that some of the highest-profile controversies in recent years involve products typically marketed to women, including contraceptive coils, vaginal mesh, and breast implants.

ICIJ’s analysis was prompted by the FDA’s refusal to release such data and was part of a broader effort led by ICIJ to collect data on injuries and deaths involving devices across five continents. The global reporting team filed more than 1,500 public records requests and collected more than 8 million device-related records, including recall notices, safety warnings and “adverse event” reports sent by various countries to the U.S. over the previous decade.

Profits over safety

As Implant Files reporters pushed health regulators to release information, they found disparities in data-collecting efforts and transparency between jurisdictions. Some of those gaps remain a challenge for patients and their advocates.

Last year, ICIJ’s media partner in Canada, CBC News, found that for nearly two decades medical device manufacturers Allergan and Mentor, a Johnson and Johnson affiliate, failed to warn local regulators about injuries related to their breast implants. Months after the Implant Files investigation exposed severe health risks associated with this type of device, the two companies quietly dumped nearly 6,000 incident reports in the Health Canada database, in violation of a law mandating manufacturers report incidents within 30 days, CBC reported.

Among the data, CBC reporters identified the adverse event report of Terri McGregor, an Ontario woman who was diagnosed with a rare cancer associated with textured breast implants in 2015. McGregor said she was “shocked” but “not surprised” to learn that the company had failed to report her problem to authorities for years. “How do you not look at this data dump by manufacturers, up to 20 years later and not see that patients’ lives mattered less than the profitability of a breast implant?” she told CBC.

Allergan declined to comment to the CBC at the time. Mentor told CBC it “has been, and remains, transparent and fully compliant with Health Canada regulations in its reporting.”

The Implant Files investigation documented the medical device industry’s reluctance to change, and its business ties to physicians. Medical device companies have paid royalties for technologies developed with doctors, and given them research grants and stock options, creating a conflict of interest that has frequently drawn the attention of government authorities, ICIJ reported.

Doctors, company insiders and government authorities have alleged in court cases that companies’ sales representatives influence surgeons’ clinical decisions and encourage them to use products in unapproved ways. Manufacturers including Medtronic, one of the world’s largest, have paid tens of millions of dollars to regulators in settlements and fines.

Since 2018, medical device companies have faced additional allegations from whistleblowers and European and U.S. authorities of violating antitrust law, and even bribery and paying kickbacks to surgeons.

Global gaps

The medical device industry is especially influential in emerging markets, where medical devices are often imported and government regulation is weak, ICIJ found.

Following the Implant Files investigation, the Indian government expanded its list of 23 devices to be regulated as strictly as drugs to include “all implantable medical devices” and machines such as those used for X-rays, MRIs and dialysis. But in terms of patient safety, India has not made much progress, according to Malini Aisola, a health advocate with All India Drug Action Network in New Delhi.

“Oversight is a huge, huge problem at the moment,” Aisola told ICIJ. “There are gaps in the entire lifecycle of a medical device,” she said.

India, which imports 75% of medical devices from abroad, is one of several countries that wave through devices, or subject them to less scrutiny, if they have already been certified as safe in Europe, the U.S. or Australia.

For products made in India, there are also no guidelines or publicly available data on how clinical investigations are conducted, according to Aisola. “We have literally no information,” she said.

Once a device is implanted in a patient, there is no long-term mechanism to monitor. The government has not implemented a functional database to collect adverse event reports and keep track of injuries and deaths possibly linked to malfunctioning devices.

The recall system appears to be equally flawed. In 2018, ICIJ’s partners at The Indian Express covered the case of Vijay Vojhala, a 44-year-old Mumbai-based former hospital equipment salesman, who suffered from vision problems, difficulty walking and irregular heart rhythms. He attributed the health issues to his Johnson & Johnson replacement hip — a product blamed for poisoning thousands of other patients. More than 4,700 people in India were implanted with the “metal-on-metal” hips before the devices were recalled or pulled from the market. But the majority of those have not been traced, according to local media. A spokesman for J&J told ICIJ that “due to patient confidentiality requirements,” the company’s DePuy India unit “does not have access to data on patients who have received an ASR hip implant.”

Reporters also uncovered allegations of influence peddling and price-gouging for cardiac devices produced by Medtronic and other large manufacturers, which denied wrongdoing. To this day, there are no regulations on marketing or pricing, leaving patients in the hands of hospitals that could push them to pay for expensive devices for marketing reasons rather than safety, Aisola said.

‘No data available’

Europe’s medical devices regulation covers more than 500,000 types of medical devices on the EU market, including pacemakers and thermometers.

ICIJ’s Implant Files investigation in 2018 identified flaws in the implant approval system of the European Union, where device manufacturers pay certification firms, known as notified bodies, to certify that high- and medium-risk devices meet European safety standards. Patient advocates have long fought to scrap the system, calling it secretive, deeply conflicted and prone to allowing dangerous devices on the market.

In 2021, a new regulation came into effect requiring manufacturers to reassess and recertify by the end of May 2024 all devices produced in Europe. But the industry has cited inspection delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain issues caused by the war in Ukraine to request a deadline extension for some devices. Early this year, the European Commission and Council agreed to give the notified bodies and manufacturers an extra four years for the recertification.

The lack of information in Europe is actually becoming worse … which does not make sense, because we’re talking about the safety of the patient. — health reporter Jet Schouten

Despite the announced reform, poor transparency in Europe remains a big challenge for journalists and the public, said Jet Schouten, a Dutch reporter whose reporting inspired the Implant Files investigation. Each EU member state has its own regulatory body and information is often not publicly available. Besides that, government agencies can choose to pay a fine instead of disclosing information, she told ICIJ.

“It’s a disaster,” said Schouten, who now works for the daily NRC. “The lack of information in Europe is actually becoming worse … which does not make sense, because we’re talking about the safety of the patient.”

Among the new measures introduced with the new law, is a database that is supposed to enable authorities to track devices and monitor all reported incidents for each. The database, called Eudamed, has a “restricted” platform for industry operators and authorities, and one is open to the public.

ICIJ tested the public interface in November 2023 and found information was missing for certificates issued to medical devices by prominent notified bodies, as well as for products by major manufacturers.

The database is still under development and is expected to be fully functional and mandatory by the end of 2027, said Stefan de Keersmaecker, spokesperson for the European Commission’s Green Deal and Health. “Therefore, data available in EUDAMED cannot be considered for the time being as representative of the medical device market,” de Keersmaecker told ICIJ in a statement.

—

A selection of stories on medical devices published by ICIJ media partners in the last five years: