(Bloomberg) — Every time the phone rings, Erik Daley can practically hear private equity coming for America’s 401(k)s.

The line has been ringing a lot lately at his modest consulting business in Portland, Oregon. For at least the past year he’s been getting a half-dozen calls a week from private equity and other firms interested in his company, and even more since the start of 2026. He’s gotten used to hearing the same question from the other end: How much for your firm?

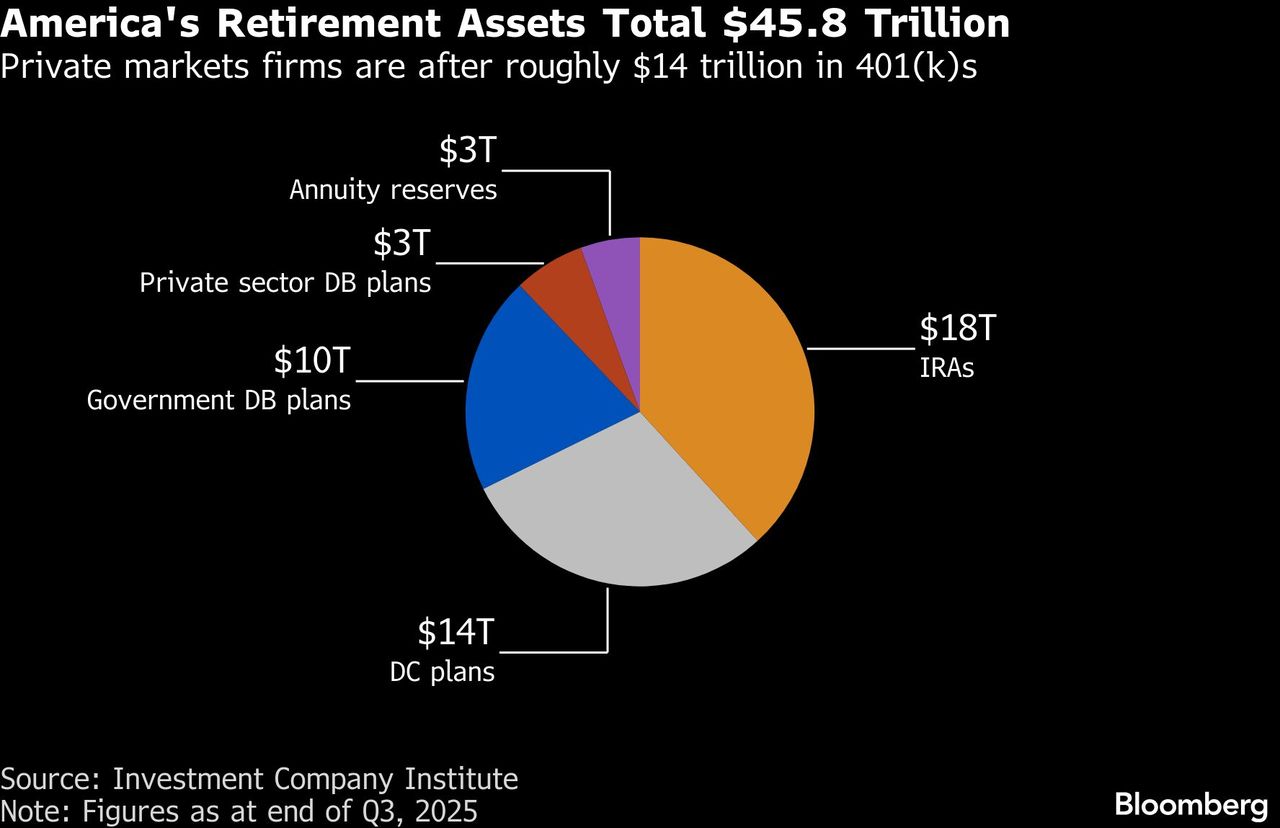

What makes little Multnomah Group a hot property: It offers advice to 401(k) retirement plans. What was once a glossless business has since become a prize for buyout firms, which see the steady growth of the $14 trillion market for US defined-contribution retirement plans as a potential source of juicy returns. Among big backers are firms such as Genstar Capital and General Atlantic.

“The primary purpose is to try and infiltrate the retail marketplace,” Daley says of the overtures. To him, the endgame is obvious: to “monetize” the nation’s 70 million 401(k) account holders.

These days, private equity is entering every corner of the vast 401(k) ecosystem that ordinary Americans count on for their golden years. Industry giants, which want to sell their products to everyday investors, have hired experts from traditional asset management companies and begun to win over brand-name mutual funds. They’ve crashed conferences, co-opted trade groups and pushed for friendly regulations, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Smaller players have bought up hundreds of independent gatekeepers — consultants, advisers and third-party administrators.

Interviews with dozens of people from across the industry, from private equity executives to individual advisers, show how broad and deep the push is. Some buyout shops see profit in handling retirement plans and ancillary businesses. Others see higher-end wealth management and its more lucrative fees as an attractive target at a time when the rich keep getting richer.

Read More: The Lawyer Gearing Up for a Fight on Private Equity in 401(k)s

Even for those not buying up 401(k)-related firms themselves, a new door is opening. Stalwarts such as Apollo Global Management Inc., Blackstone Inc., KKR & Co. and Carlyle Group Inc. want to sell their rarefied brand of investing to the masses, and the way is clear.

The private-asset industry has been lobbying for years for the government to bless the inclusion of alternative investments in defined-contribution retirement plans. In August, President Donald Trump signed an order aimed at easing access to private equity, real estate, cryptocurrency and other alternative assets in 401(k)s. Now, much-anticipated guidance from the administration is expected any day. New funds featuring private assets are being launched, and some in the industry are working to seed established ones with alternative investments. Executives predict that 2026 might just be the year their long campaign starts paying off.

“It’s already happening,” says Jonathan Epstein, founder of the Defined Contribution Alternatives Association. His trade group, founded in 2015 long before the debate became prominent, advocates adding non-traditional investments to 401(k) plans and counts among its members Goldman Sachs Group Inc., KKR and the City & County of San Francisco.

Heather von Zuben, global head of retirement solutions at Blackstone, said it’s difficult to predict the speed of adoption across the industry, but the firm is “seeing increasing interest” in private markets products. KKR, Apollo and Carlyle declined to comment.

The question is whether the industry push will pay off for people dreaming of comfortable retirements.

Privately, some consultants and advisers — including ones who now find themselves working for private equity-owned companies — worry that alternative asset managers ultimately might try to keep winning investments for themselves and their institutional clients and dump losing ones on less-discerning retail investors, according industry participants who spoke to Bloomberg. Private markets executives say the concern is unfounded.

Short term, the timing looks iffy for Main Street. Pension funds and endowments that have long powered private equity have begun to pull back. Returns don’t look as good as they used to.

“The push for private assets into retirement plans is entirely supply-driven,” George Webb, chief executive officer of advice firm Pension & Wealth Management Advisors. “Sponsors, advisers and participants are not asking for it at all.”

Some of that may have to do with a run of stellar returns in the stock market, where the S&P 500 Index has notched doubled-digit gains in six of the past seven years. Private, less-liquid investments are an easier pitch when better-known strategies falter and bring the benefits of diversification into view.

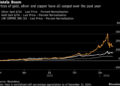

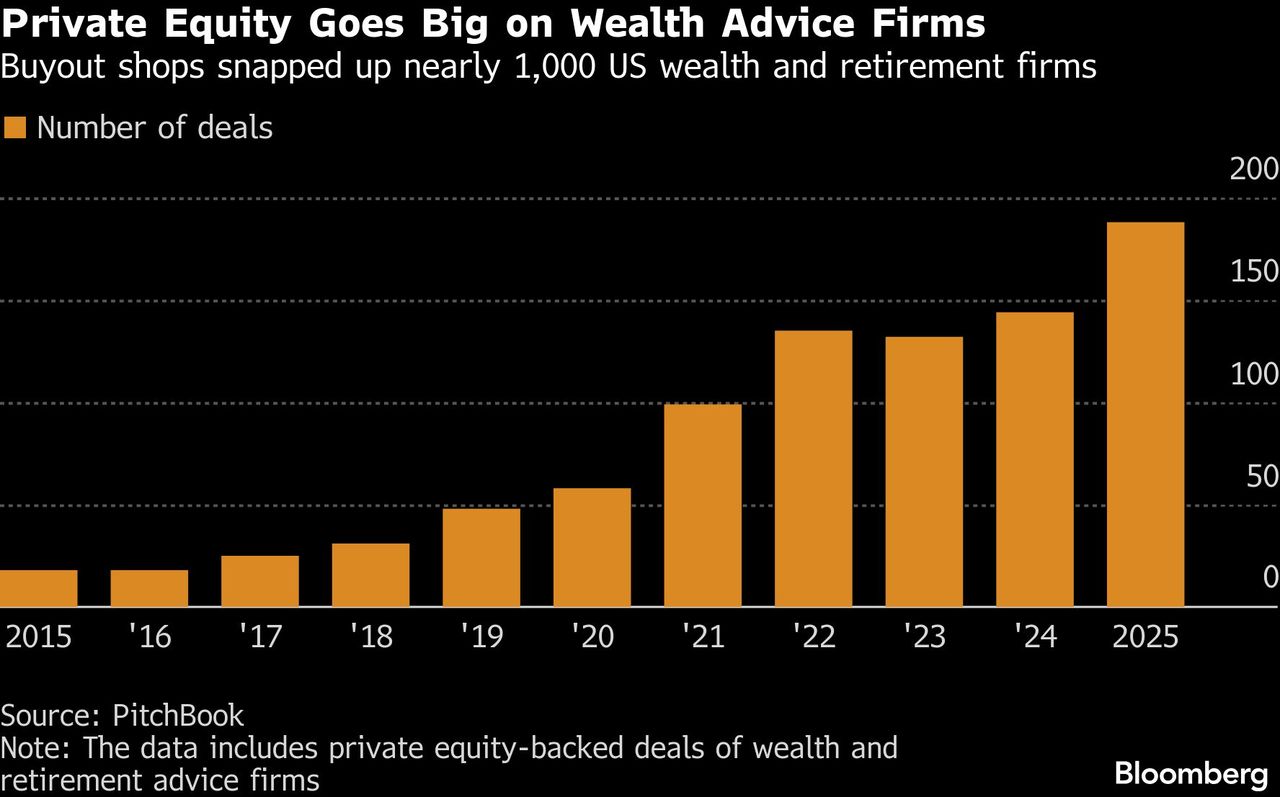

Until then, one way to drum up 401(k) investors is to win over people in the 401(k) business. Apollo, Carlyle and KKR have all recently hired veterans from the retirement and fund industry. Over the past decade, smaller private-equity firms and financial companies backed by them have acquired more than 900 independent firms that provide retirement and wealth-management services, according to data collected by PitchBook. In January 2026 alone, 20 such deals were made.

Mercer, one of industry’s largest consulting firms, has come out in favor of integrating private assets into 401(k) plans. Others worry that if they don’t act fast, they might miss out on a big moneymaker, according to people familiar with the matter.

Trouble is, most 401(k) investors seem perfectly fine with the options they have. Only a handful of plans have said they plan to add private assets to their menus. Many advisers say the companies they work with have no interest in the debate, or lack the understanding of what private markets are.

Ted Benna says he’s surprised at how many choices people have already. He ought to know: Benna is widely considered the father of the 401(k). He designed the first one, named after an obscure provision of the US tax code, way back in 1981.

Benna can hardly believe what’s happened since. His simple idea — having employees contribute a portion of their pretax wages to company retirement plans and having their employers match those contributions with tax-deductible contributions — has exploded into a multitrillion-dollar industry.

Epstein’s trade goup, Dcalta, celebrated Benna with a lifetime achievement award last November. The venue: a conference attended by alternatives supporters. Benna says he felt honored, but he worries that people might not fully understand the array of investments they’re being offered.

“We’ve gone from 401(k)s having only two investment options that took me two minutes to explain,’’ Benna says, “and we’re now moving to a huge complexity that participants will have to deal with.”

Such qualms aside, the Investment Company Institute, a trade group for asset managers, has become a leading promoter of the idea. As private equity has gained power in Washington, the trade group has made the “democratization’’ of private-market investments a top priority.

“We’re not going out saying to Americans around the country, ‘Hey, get into this now,” says ICI Chief Executive Officer Eric Pan. “What we’re saying is that we believe there’s a legitimate case for retail access to private markets and we want to make sure the policy environment makes it possible for this to happen.”

Even mutual-fund stalwarts like T. Rowe Price are getting into the act. Long a 401(k) fixture, Baltimore-based T. Rowe has teamed up with Goldman Sachs to create private-asset funds for retirement accounts. It’s also held exploratory talks with alternative investment managers about incorporating private assets into established retirement accounts, according to people familiar with the matter. T Rowe declined to comment. BlackRock Inc., State Street Corp.’s investment arm and even Vanguard Group are launching their own private-markets funds.

Change is afoot across the retirement industry. Take insurance broker HUB International. Over the past decade, HUB has added plan consultants in California, retirement advisers in New York, wealth managers in Florida. The coast-to-coast spree has put 10,000 401(k) plans and $178 billion of assets under its purview. A key motivator: its biggest shareholder, private-equity firm Hellman & Friedman, whose past conquests include Levi Strauss & Co. and DoubleClick Inc.

Brian Collins, chief investment officer of HUB’s private wealth and retirement business, acknowledges that many people aren’t all that interested in alternative investments. But HUB says private assets probably make sense for some 401(k) savers. It often raises the idea with its clients — mostly small and midsize retirement plans.

“Retirement advisers, if they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing they’re staying current on all the developments,” Collins says. “Whether they’re owned by private equity or the partners, it’s common to stay abreast of it.”

HUB plans to go public at some point. That would offer an exit for Hellman & Friedman — and leave behind an advisory firm that is comfortable telling private equity’s story.

Another insurance brokerage and consultant under private equity ownership, OneDigital, has been working with alternative asset managers including Blackstone, Apollo and Ares Management Corp. to add private assets to a range of established adviser-managed multi-asset portfolios.

Michael Esselman, the CIO of the retirement and wealth business, says advisers like OneDigital, rather than employees, should determine what kind of investments are or aren’t offered to workers.

“I don’t think that choice should sit with the participant,” he says about introducing alternative investments.

“They don’t know what private credit is,” Esselman says of 401(k) account holders. “They don’t even know the difference between equities and bonds.”

Another key constituency for private equity: the often unsung firms that administer retirement plans and maintain records. Administrators are a key point of contact for plan sponsors and speak regularly with consultants and advisers. When they talk, people listen.

Empower, one of the biggest around, has become a vocal champion of alternative investments. With $2 trillion in assets under administration for more than 89,000 defined-contribution pension plans, the company has launched a series of funds in collaboration with Apollo, Partners Group and Neuberger Berman, among others. At the start of the year it also partnered with Blackstone. One of its competitors, Voya Financial, has partnered with private-markets giant Blue Owl Capital to create funds that Voya’s investment arm can offer to clients. Other record keepers are warming up to the private markets push, according to people familiar with their thinking.

Back in Portland, Erik Daley insists that he isn’t selling. He says he doesn’t trust private-equity money to look out for 401(k) clients — selling could muddy the priorities of advisers, who would have to look out for the interests of their new owners in addition to clients.

“It creates a potential area of conflict,” Daley says.

To contact the author of this story: Loukia Gyftopoulou in New York at [email protected]

© 2026 Bloomberg L.P.