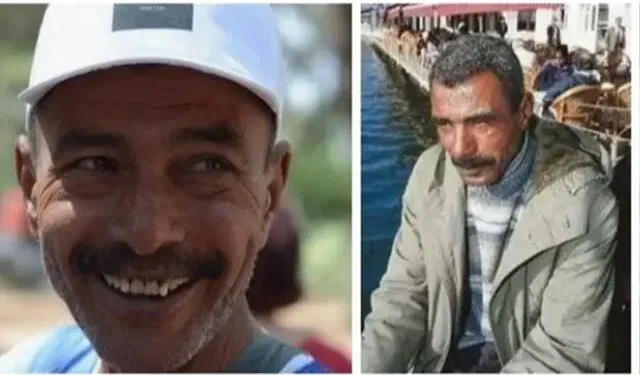

Mustafa Olpak grew up on the Aegean coast of Turkey believing his family’s story was simply one of migration, loss, and quiet survival. He knew his ancestors had lived on Crete and that they were among the Muslims uprooted in 1923 during the population exchange between Greece and Turkey. What he did not know—what no one in his family dared to speak about—was where they had come from before Crete, before the Ottoman household that owned them, before the Indian Ocean crossing that had erased their names.

It was an elderly relative’s offhand comment, spoken almost as a warning, that finally pushed him to begin asking questions: “Our people came from Africa, but that is a painful story. Leave it alone.”

He did not leave it alone.

Instead, Mustafa Olpak became the first Afro-Turk to methodically trace his family history, a journey that began in the archives of Crete and Istanbul but led him, unexpectedly, to Kenya. By cross-checking Ottoman household records, oral histories from Afro-Cretan families, and scholarship on East African caravan routes, he reached a conclusion that surprised even him: his ancestors had been Kikuyu, taken from the central highlands of Kenya in the late nineteenth century.

For a people rooted in the ridges and valleys of Mount Kenya—hundreds of kilometers from the Indian Ocean—this raised a difficult question that still lingers in Kenya today: How did highland farmers end up as slaves in the Ottoman Empire?

– Advertisement –

It is a question the late Kenyan historian Bethwell Ogot, one of Africa’s most respected voices on continental history, helped us frame. Writing in UNESCO’s General History of Africa, Ogot described the slave trade as an “endlessly bleeding wound,” a catastrophe that drained populations, warped economies and left scars across both the coast and the interior. Yet in Kenya, public memory of slavery is often confined to the coast—Fort Jesus, the old slave routes around Mombasa, the dhow imagery taught in school. The idea that Kikuyu farmers in the highlands could be linked to a Black community in modern Turkey feels, at first, almost impossible.

Olpak’s research, and the work of historians of the Indian Ocean world, helps explain that link. Tanzanian historian Abdul Sheriff, a leading scholar of East African maritime history, has spent decades showing that the Indian Ocean slave trade was not a sideshow to the Atlantic trade but an older, long-lasting system that tied the Swahili coast to Arabia, Persia, India and the Ottoman Empire. Mauritian historian Vijayalakshmi Teelock and others have reinforced this view, documenting how nineteenth-century plantations in Zanzibar and the western Indian Ocean drew in tens of thousands of enslaved East Africans.

For Kenya, their work has a particularly unsettling implication: the slave frontier did not stop at the coast.

In the 1870s and 1880s—before British abolition efforts really bit—Swahili-Arab caravans pushed deeper inland in search of ivory and, increasingly, people. Missionaries and travelers recorded caravan routes creeping toward the southern Aberdares and the slopes of Mount Kenya, while oral traditions in central Kenya quietly recall the disappearance of young people “taken by strangers” during years of famine and insecurity. Historians of caravan porters and routes have since mapped how paths from the highlands intersected with the wider East African trade network, making even inland communities vulnerable once demand for labor skyrocketed.

It was in this violent moment that Olpak believes his ancestors were seized—most likely in a Kikuyu community trading or interacting at the fringes of caravan routes. Chained into slave coffles, they would have been forced on a weeks- or months-long march toward coastal entrepôts such as Mombasa or Bagamoyo, joining thousands of other East Africans funneled into the Indian Ocean slave economy.

From there, the trail grows more familiar to historians, if no less brutal. Records of the Indian Ocean slave trade show enslaved East Africans being shipped by dhow to Zanzibar and onward to Oman, the Arabian Peninsula and, crucially in this case, Ottoman territories around the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. Some of those captives were purchased for domestic service or agricultural work on Crete and in nearby Ottoman provinces—including parts of today’s Greece and Cyprus—where African-descended communities would quietly take root.

This is where Olpak’s family story resurfaces in the written record. Afro-Turkish oral histories and Ottoman registers point to a population of African slaves and their descendants on Crete in the nineteenth century—people brought from East and Northeast Africa to work in homes and fields, their exact ethnic origins blurred under the generic label “Zanj.” Olpak’s painstaking reconstruction—triangulating his family’s stories, Cretan documents, and East African scholarship—convinced him that behind that vague label, in his case, stood Kikuyu ancestors torn from the Kenyan highlands.

Legally, the world around them was shifting. By the 1880s, the British Royal Navy was aggressively patrolling the Indian Ocean, and treaties between London and the Sultan of Zanzibar sought to choke off the export of slaves from East Africa. In 1897, the British forced Zanzibar’s ruler to issue a decree abolishing slavery’s legal status in the archipelago, with a final measure in 1909 extending emancipation to women held as concubines—often the last category the authorities hesitated to touch.

The 1897 abolition decree technically applied to the 10-mile coastal strip under the Sultan of Zanzibar’s authority, which included parts of present-day Kenya. However, enforcement was inconsistent, and debates in the British Parliament show that slavery and quasi-slavery continued in practice in these coastal areas into the early 1900s, with legal and social remnants persisting well into the first decade of the twentieth century.

What this means for Olpak’s story is important: his ancestors were almost certainly captured before these abolition measures took full effect, at a time when raiding into the interior was still possible and profitable, even as diplomatic pressure on the trade was mounting. Abolition on paper did not magically free everyone. As one historian of East Africa has put it, slavery had a “long tail”—illegal trafficking, coerced labor and social stigma continued well into the colonial period.

By the time the Ottoman Empire crumbled and Crete passed permanently into Greek hands, Olpak’s ancestors had lived on the island for generations. Their children spoke Greek, worked Cretan soil, and practiced Islam under Ottoman rule. Then, in 1923, came the Lausanne Convention and the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, which forcibly uprooted about 1.5 million Orthodox Christians from Turkey and roughly 500,000 Muslims from Greece and its islands. Among those Muslims were Afro-Cretan families—Africans by ancestry, Cretan by culture—who were loaded onto ships and told they were now “returning” to a homeland they had never seen.

They landed in western Anatolia, in villages around Izmir, Aydın, Muğla and Balıkesir, where their descendants still live today. Their story, however, remained largely invisible. Afro-Turks were folded into the new republic through a deliberate process of “Turkification”; their Africanness was quietly downplayed, their memories of slavery and Cretan exile domesticated into a more palatable narrative of national unity.

Even within Turkey, many citizens are still surprised to learn that there is a Black Turkish minority whose ancestors arrived not as guest workers or recent migrants, but as slaves centuries ago. Across the wider African continent, the ignorance is even deeper. Ask most Kenyans about the diaspora, and you will hear about African Americans, Afro-Brazilians, or Caribbean communities. Few know that there are Black populations in Turkey, Cyprus and Crete whose roots trace back to East Africa, including Kenya—a remnant of the Ottoman Empire’s entanglement in the Indian Ocean slave trade.

It was against this backdrop of silence and erasure that Mustafa Olpak decided to act. He did not just want to know where his family came from; he wanted the world to know that Afro-Turks existed at all.

His 2005 memoir, Kenya–Girit–İstanbul: Köle Kıyısından İnsan Biyografileri (“Kenya–Crete–Istanbul: Human Biographies from the Slave Coast”), was the first book in Turkey to publicly trace a family’s journey from East African enslavement to Ottoman domestic servitude to citizenship in the modern republic. Turkish journalists quickly dubbed it a kind of Turkish Roots, echoing Alex Haley’s famous reconstruction of his family’s Gambian origins.

But whereas Haley’s story helped African Americans see themselves in African history, Olpak’s work offered something slightly different: it forced both Turks and Africans to see the Indian Ocean as a shared historical space. For Afro-Turks, it meant rediscovering that their ancestors were not simply “from Africa,” but from specific places—Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Tanzania, and, in Olpak’s case, the Kikuyu highlands of Kenya. For Kenyans, it meant realizing that the slave trade Ogot called an “endlessly bleeding wound” did not just send people westward across the Atlantic; it also sent them northwards into empires and societies we rarely associate with blackness.

Olpak did more than write. He founded the Afrika Kültür ve Dayanışma Derneği—the Africans’ Culture and Solidarity Society—to give Afro-Turks a collective voice. The group helped revive Dana Bayramı, a traditional spring festival with African roots that had been pushed underground for decades, and began pushing for broader recognition of Afro-Turks in public life. Through interviews, cultural festivals, and partnerships with scholars, they started documenting stories that might otherwise have vanished as the oldest generation passed away.

For many Afro-Turks interviewed in recent years, discovering that there are people in Kenya who care about their story has been deeply moving. For many Kenyans, learning that there are Kikuyu-descended families in western Turkey is equally jarring. It complicates comforting narratives about “home” and “diaspora,” and it raises awkward questions about what else our history books have left out.

Yet there is also a kind of healing in this recognition. When Kenyan historians like Ogot insist that Africa must reclaim its past in “authentic and all-encompassing form,” they are calling for exactly this kind of connection—for us to see that a boy in Izmir and a girl in Murang’a might share more than a faith or a language; they might share bloodlines ruptured by the Indian Ocean slave trade and partially restored through memory.

Mustafa Olpak died in 2016, but his legacy lives on in the Afro-Turks who now speak openly about their ancestors, in the Kenyan scholars and journalists who are finally tracing these links, and in the quiet shock of recognition when a Kenyan reader realizes: our people are there too.

By Njuguna Kabugi/Diaspora Messenger contributor