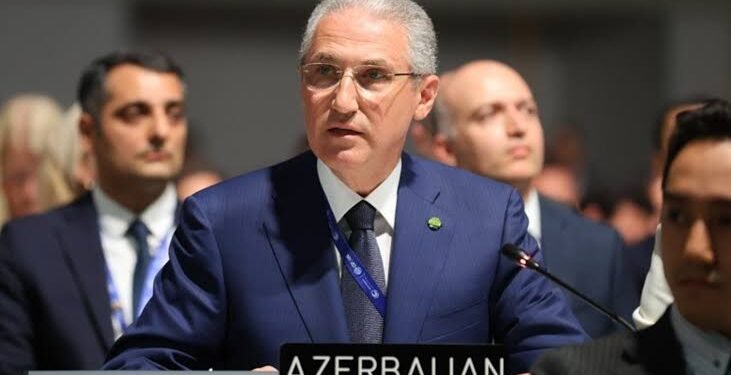

The stakes are once again high as the world heads to the 29th Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP29) from November 11-22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan, which takes place in a year of record-breaking temperatures, unprecedented weather events across the globe, off-the-rails climate policies, missing climate finance, and just days after the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States.

This year’s focus, climate finance, underscores the urgency of delivering funding at a scale and ambition sufficient to confront the climate crisis and help with a fast and fair energy transition in the Global South. Yet, if governments’ failure to address the key driver of the crisis — fossil fuel production and use — persists, even the most ambitious finance measures will fall short.

No climate finance would be enough without a full, fast, and fair phase-out of fossil fuels. Despite decades of discussions and the largely absent mention of fossil fuels, governments are way off track on their commitments to keep global warming below the 1.5°C limit and to avert the most catastrophic impacts on human rights.

As world leaders convene in Baku, they face a pivotal moment: COP29 is expected to reach an agreement on carbon markets — a dangerous distraction allowing countries to trade greenhouse gas emissions “credits” rather than reduce emissions to help achieve climate goals — and to signal how they will strengthen their national climate plans (NDCs) due in early 2025 (hint: committing to an urgent, full, and timebound fossil fuel phaseout, without loopholes or limitations, is key).

Delivering on Climate Finance

Dubbed the “Finance COP,” COP29 will focus heavily on adopting a new climate finance target, marking the first time in 15 years that countries will reevaluate the amount and type of finance developing countries receive to pay for climate action since the $100 billion annual target was set in 2009. This is a target that the world’s developed and wealthiest nations have consistently failed to meet, as the $100 billion by 2020 goal was reached two years too late, breaking trust with developing countries and those most vulnerable to climate change and hampering global climate progress.

After years of unmet commitments and, more recently, technical dialogues about both the quantity and quality of the finance, countries will commit to a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance — a chance to commit to climate finance that matches the scale of today’s crises. The NCQG is not intended to solve all climate finance issues, but it is a crucial piece of the puzzle.

The financial goal is not symbolic or optional: setting and delivering it is a legal obligation

The finance goal is not merely symbolic. Committing to and actually providing adequate and necessary funding is critical and essential to helping countries vulnerable to climate change pursue clean energy and other low-carbon solutions, build climate resilience, and fulfill or strengthen their national climate pledges. Countries in vulnerable regions need reliable resources to transition fairly, adopt clean energy, and prepare for worsening climate impacts.

The magnitude, form, and source of the financing

In Baku, negotiators and political leaders face key decisions, including the ultimate NCQG top-line dollar figure — in billions or trillions — and whether separate targets will be established for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. Other key considerations include which countries will be included as those who provide finance under this goal, whether certain financial instruments (such as grants or concessional loans) will be favoured, and how they will ensure transparency.

Climate finance must encompass money for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage

In addition to finance for mitigation and adaptation, wealthy nations have an obligation to provide climate finance to developing countries for loss and damage rather than continuing their years of delay and obstruction to avoid remedying the harms they have caused.

It’s past time for empty promises and failing to deliver. We need real finance, and we need it now.

Carbon Markets Are Not Climate Finance

With increased attention to the massive funding gap for climate mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage, growing numbers of carbon market proponents are fashioning carbon trading as climate finance. But purchasing carbon credits to obtain a free pass to continue polluting, chiefly through fossil fuel production and use, cannot be considered true climate finance. Carbon offsets that allow polluters to buy emissions reductions from other countries instead of reducing their own emissions do not enhance overall levels of climate mitigation or adaptation — which is the very defining feature of climate finance. They must not be used as an escape hatch or excuse for developed countries to avoid their legal obligations to provide financing for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage, particularly in the Global South.

Wealthy countries that bear the greatest cumulative responsibility for the climate crisis are overdue on their payment of predictable, new, and additional grants-based climate finance, and they must agree to put real money on the table — not hide behind dangerous schemes like carbon markets and offsets that may be generated from illusory technologies for CO2 “removal” and geoengineering. These carbon markets primarily serve to delay effective climate action and bring risks to peoples and the environment.

Global South countries and communities on the front line of the climate crisis need real climate finance and should not be forced to accept carbon markets and the pressure to generate offsets to allow Global North polluters to continue business as usual because Global North countries continue to fail to live up to their obligations. Only offering a form of financing that ultimately undermines ambition and global climate action and likely increases the cost of mitigation measures Global South countries will have to take now and in the future to meet their climate goals is not in line with climate justice.

One of the thorniest issues at COP29

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement allows countries to trade carbon credits toward achieving their national climate goals. For example, a country rich in tropical rainforests could sell credits calculated on the basis of deforestation avoided or CO2 absorbed by forests to generate funds for forest protection (carbon offsets). However, that country wouldn’t get to count those emissions reductions or removals toward their own climate mitigation targets; instead, the countries purchasing the credits would count the resulting emissions reductions or removals toward their own national climate targets.

It’s fundamentally flawed — these Global South credit-generating countries are effectively trading away the cheapest climate action. Rules for these carbon markets have been on the agenda of the climate talks for years, and while a basic rubric was adopted at COP26, fully operationalising the carbon markets has lagged behind many of the other rules for implementing the Paris Agreement. And they have to be ironed out before trading can begin.

Many carbon market mechanisms create loopholes for polluters while posing significant risks to human rights, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the environment. They also serve as a dangerous distraction from the real climate action that is needed. The fundamental flaws make it all the more critical that, if markets are to be used, the right rules for trading carbon credits are agreed to before any activity takes place. It is exceedingly important to minimise the environmental damage of international carbon markets and mitigate the risk as they undermine global emission cuts or impact the rights and livelihoods of communities worldwide.

Since failing to reach a full agreement on the Article 6 rules at COP28, Parties have tried to find common ground. Notably, the Supervisory Body for the newly named Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), which involves carbon crediting between countries and various other entities, has reached conclusions on a flawed grievance mechanism and a Sustainable Development Tool.

The Supervisory Body has also tried again to reach an agreement on two standards (methodology requirements and activities involving removals) that provide the technical underpinnings for carbon crediting and that have not been accepted by the Parties in their previous iterations at COP27 and COP28 Concerningly, this time, the Supervisory Body has taken a different approach.

Rather than presenting the recommendations to the COP as in years past, the Supervisory Body claims these standards are fully operational and just need to be noted by the Parties in Baku. This attempt to circumvent oversight could set a dangerous precedent and it undermines the integrity of the PACM from the beginning.

Rather than focusing on this false solution to fossil fuel phaseout and finance, Parties should step up and take the climate action needed and put real money on the table to support the ambition required to tackle the climate crisis.

A strong financial outcome without loopholes in Baku will help ensure that all countries have the resources they need to pursue a just transition to a climate-safe, fossil-free future centered on human rights and on the needs and demands of the poorest countries in the most vulnerable contexts.

At a moment when countries are reevaluating their climate commitments, COP29 also offers a chance for major emitting nations to demonstrate stronger leadership, putting forward more ambitious climate plans and recommitting to deliver on these.

A Finance COP will be meaningless if leaders fail to take clear, actionable steps to commit to real finance and to end all fossil fuels, fast, fairly, and forever.

By Erika Lennon, Senior Attorney for the Climate and Energy Programme at the Centre for International Environmental Law, and Rossella Recupero, Communications Campaign Specialist at the Centre for International Environmental Law