ADF STAFF

Some analysts worried that Somali pirates were staging a comeback when a Maltese-flagged merchant ship, the Ruen, was hijacked off the coast of Somalia in December 2023, marking the first successful attack on such a ship in the region in six years.

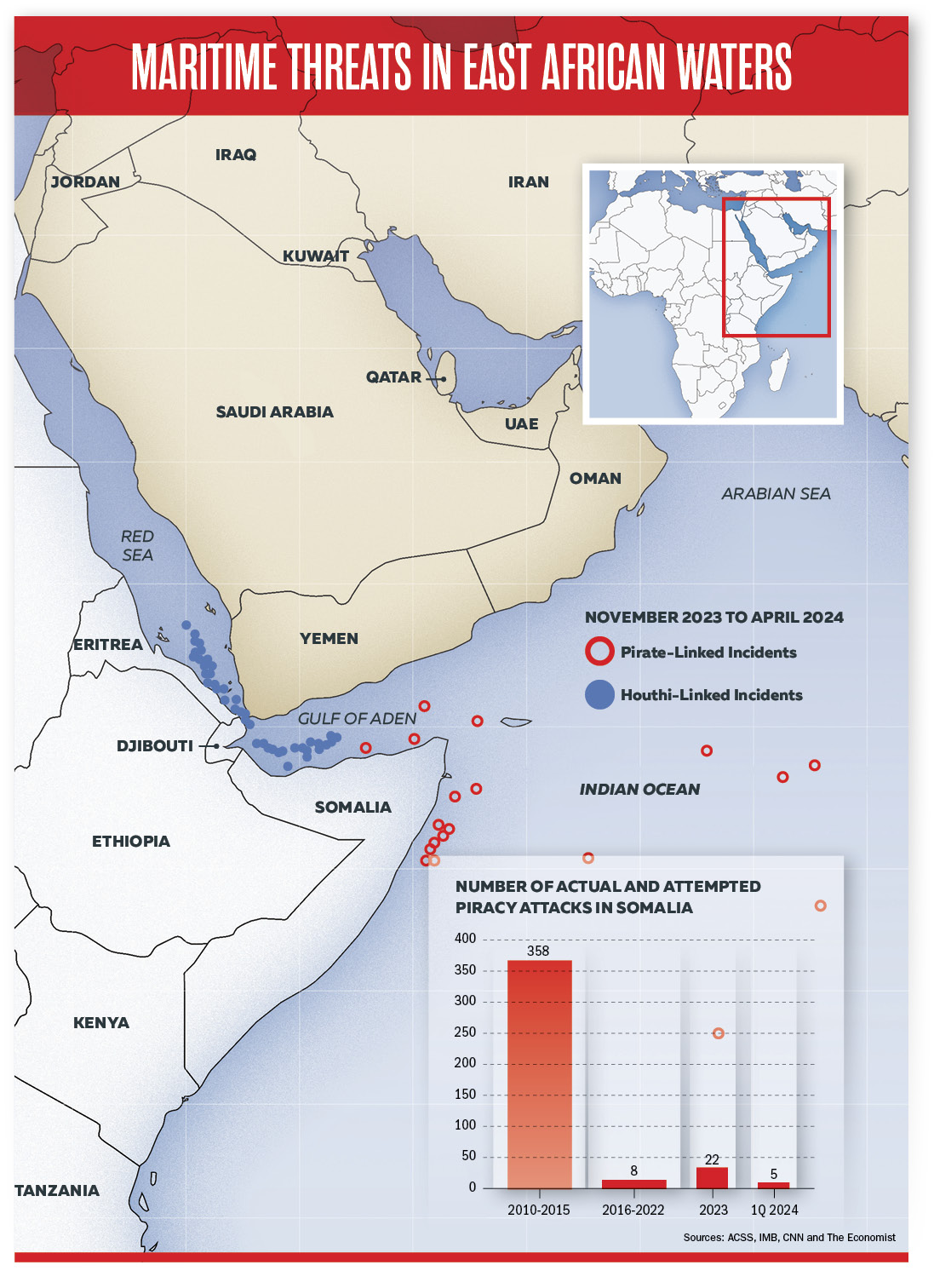

Increasing piracy in the ensuing months left little doubt that Somali pirates are back and seemingly more capable than ever, launching attacks at great distances from Somalia’s coast.

There were 33 incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships by Somali pirates in the first three months of 2024, an increase from 27 incidents over the same period in 2023, the International Maritime Bureau reported. During that time, pirates held 35 crew members hostage, kidnapped nine and threatened another.

“This is a major, major uptick in terms of pirate activity,” Ian Ralby, a maritime security expert and chief executive officer of I.R. Consilium, told ADF. “It’s the most activity we’ve seen in the last six years, and it’s probably the hottest period we’ve had since the precipitous decline back in May 2012.”

Pirates held the Ruen until March, when the Indian Navy rescued the ship and 17 hostages. The Indian ship captured 35 armed pirates during a nearly 40-hour operation off Somalia’s coast.

The Indian Navy said it tracked the vessel before launching the rescue operation and intercepting the ship about 260 nautical miles east of Somalia. It confirmed the presence of armed pirates through a ship-launched drone.

“In a reckless hostile act, the pirates shot down the drone and fired at the Indian Naval warship,” an Indian Navy spokesperson said in a defenceWeb report. “In a calibrated response in accordance with international laws, [an Indian Navy ship] disabled the ship’s steering system and navigational aids, forcing the pirate ship to stop.”

Officials arrested the pirates and took them to India for prosecution. Ralby is eager to learn about their legal outcome.

“Nothing changes the risk-reward calculus more than being prosecuted and sentenced to a long time in jail when it comes to piracy,” Ralby said. “That’s a risk most do not want to take, and the reward is difficult to achieve if you have the ever-presence of naval forces either willing to take aim at you with a rifle or collect you and take you into court.”

“Nothing changes the risk-reward calculus more than being prosecuted and sentenced to a long time in jail when it comes to piracy,” Ralby said. “That’s a risk most do not want to take, and the reward is difficult to achieve if you have the ever-presence of naval forces either willing to take aim at you with a rifle or collect you and take you into court.”

The Ruen likely was used as the base for the takeover of a Bangladesh-flagged cargo ship off the coast of Somalia in mid-March, the European Union naval force said. This is a common tactic used by Somali pirates, most of whom hail from semiautonomous Puntland State.

Somali pirates in January 2024 hijacked eight fishing vessels in the Western Indian Ocean and used at least five of them to conduct more attacks, according to the Neptune P2P group, an international private security company. The rise in Somali piracy coincides with international navies leaving waters around Somalia to defend against repeated attacks by Yemen’s Houthi militia in the Red Sea and other regional waters.

“As we see the Houthis launch their assaults on global maritime commerce, obviously everyone in the region has diverted their attention to protect shipping and to protect the massive increase in the volume of traffic along the African coastline that have rerouted to avoid the Red Sea altogether,” Ralby said. “It’s a perfect scenario for pirates to look to gain criminal advantage once again.”

Two Somali gang members confirmed to Reuters that they were taking advantage of the distraction provided by Houthi strikes several hundred nautical miles to the north to get back into piracy after lying dormant for nearly a decade.

Abdinasir Yusuf of the Puntland Development and Research Centre attributed the surge in Somali piracy to political strife that distracted security forces, as well as the presence of foreign fishing vessels that undermine the livelihoods of local fishermen.

“Piracy never stopped,” Yusuf told The Economist, “it was overpowered.”

Disrupting Global Trade

The converging Somali pirate and Houthi attacks are disrupting global trade. The waterways off Somalia are some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Every year, about 20,000 vessels pass through the Gulf of Aden on their way to and from the Red Sea and the Suez Canal — the shortest maritime route between Asia and Europe. The attacks, which often include ransom demands, have increased security and insurance costs.

The hijackings have extended the area in which insurers impose additional war risk premiums on ships. These premiums are an additional cost that insurance companies charge to cover the risks associated with war, terrorism and political unrest in areas of conflict. War risk premiums add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of a typical seven-day trip, insurance industry officials told Reuters. The cost to hire a team of private armed guards aboard ships for three days also increased in February 2024 to between $4,000 and $15,000 monthly, a roughly 50% increase.

Somali pirates on April 15 collected a $5 million ransom after freeing the Bangladeshi cargo ship Abdullah and about 23 crew members. Pirates overtook the coal-carrying vessel about 600 nautical miles east of Somalia in mid-March.

“The money was brought to us two nights ago as usual,” Abdirashiid Yusuf, one of the pirates involved in the hijacking, told Reuters. “We checked whether the money was fake or not. Then we divided the money into groups and left, avoiding the government forces.”

In their heyday, Somali pirates collected $53 million in ransom payments every year, according to the World Bank. Piracy reached its peak in Somalia in 2011 when pirates launched 212 attacks, during which 1,200 seafarers were held hostage and 35 died. That year, the Oceans Beyond Piracy monitoring group estimated that piracy cost the global economy about $7 billion.

Officials recorded only five Somali pirate attacks between 2017 and 2020. The lull was attributed to coordinated anti-piracy naval operations, safety measures such as armed guards on ships, and increased prosecution and imprisonment of pirates.

Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud acknowledged the renewed piracy threat in March 2024. “If we do not stop [piracy] while it’s still in its infancy, it can become the same as it was,” Mohamud told Reuters.

Analysts at The Economist doubt that piracy will return to 2011 levels because opportunities exposed by the Houthis eventually will abate.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Al-Shabaab Involvement

Reports emerged in early 2024 that al-Shabaab militants in Somalia’s northern Sanaag region had extended an offer to cooperate with pirates. Analysts believe the deal is to provide protection to pirates in exchange for 30% of all ransom proceeds and a cut of any loot, Emirati newspaper The National reported. The deal could provide al-Shabaab with critical funds after the Somali government clamped down on its other illegal money sources and froze its bank accounts. The terrorists also are suspected of negotiating with pirates and Houthi rebels to acquire weapons.

The Houthi attacks on maritime commerce “are a great inspiration to anyone who has the capacity and intent to attack shipping” because the Houthis successfully gained global visibility, legitimacy and credibility, allowing them to recruit more members, which may appeal to pirates and their supporters, Ralby said.

“That’s where the concern remains for al-Shabaab to — almost out of jealousy over the Houthi rise to prominence — do something to regain its own visibility and momentum,” Ralby added. “So, if al-Shabaab is watching carefully, which I’m sure they are due to the longstanding arms trafficking flow that went through al-Shabaab up to Yemen, I suspect that al-Shabaab will look for similar opportunities to gain momentum and prominence. That’s an area of real concern.”

Pirates historically have not been attached to terrorist organizations, as pirates almost solely seek money, while terrorists seek financing for ideological reasons. Linking pirates with terrorists can be dangerous, Ralby argued.

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

“Why? Because if we are labeling pirates as terrorists that makes it very hard to negotiate a ransom,” he said. “If we’re trying to get kidnapped personnel or a kidnapped vessel away from the control of pirates, and we call them terrorists, we hamper our own ability to get them back.”

He said that he hopes the “fiery resistance” to piracy by the Indian Navy and other international forces will deter further attacks, “although we’ll likely see more.”

One important tool in the fight against piracy is the Regional Coordination Operations Center (RCOC) in Seychelles, which organizes regular maritime security operations.

The RCOC in December expanded its area of responsibility and now coordinates operations to counter sea crimes for 21 countries.

“That is a very strong mechanism that did not exist previously,” Ralby said. “So we should be able to see more effective deterrence and hopefully any kind of operational activity on the water is paired with legal finish in a court in order to make sure that the pirates are truly held accountable and not just caught and released. That is not an effective deterrence.”