Last summer, gray-green grasshoppers crawled and skittered and flew so thickly across Monty Lesh’s land that the ground itself appeared to be moving. As they tumbled through the grass, their powerful jaws munched the blades down to nubs.

Periodic swarms of grasshoppers provide food for species ranging from sage grouse and songbirds to swift foxes and trout. But for ranchers who need grass to feed their livestock, the outbreaks can be devastating.

“In the middle of July, grasshoppers moved in, and by the middle of August we were supplementing feeding because they stripped everything,” Lesh said from his ranch near Miles City, Montana. “This year, it could be infestations of epic proportions.”

“This year, it could be infestations of epic proportions.”

Historically, grasshopper outbreaks have been triggered by consecutive wet springs, which allow eggs to survive and provide plenty of food for juveniles. But as the climate changes and storms, fires and droughts become increasingly destructive and erratic, the outbreaks may be worsening, too. And depending on who you ask, the go-to solution — spraying chemicals including one called diflubenzuron — is either a lifesaving intervention or a treatment that can be worse than the disease.

“The grasshoppers will win”

Even the worst of the recent outbreaks — or “plagues,” as some ranchers call them — bear little resemblance to the waves of Rocky Mountain locusts that blackened the region’s horizons in the 1800s. That species was extinct by the early 1900s, likely due to the European settlers who tilled the soil where the locusts laid eggs.

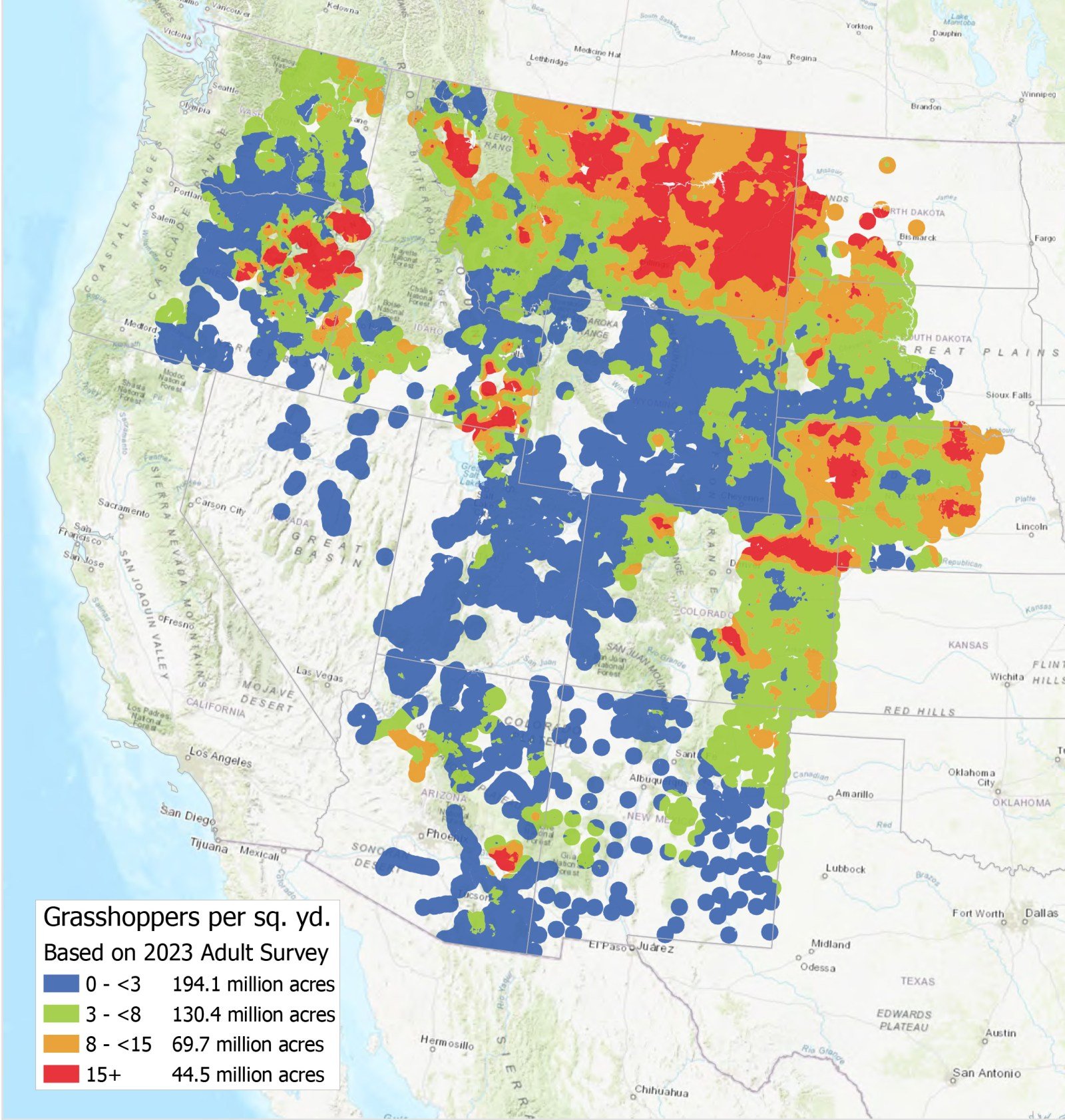

But grasshoppers can still become numerous enough to strip thousands, if not tens of thousands, of acres of valuable pastureland — which is exactly what happened last summer, and the summer before that, and the one before that. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is predicting another bad season this summer, largely based on data from last summer.

“Old-timers used to claim you’d have three bad grasshopper years, and they would go away,” said Lon Reukauf, a rancher in southeastern Montana. But several of Reukauf’s neighbors are struggling through their fourth or fifth consecutive summer of outbreaks.

David Lightfoot, a grasshopper ecologist and University of New Mexico professor who has documented outbreaks for the past 30 years, said that overgrazing is at least partly responsible for the run of bad years. Too many cows on the landscape for too long has caused a kind of desertification, he said, leading to a decline in the less-destructive specialist species — grasshopper species that thrive only in certain environmental conditions — along with a boom in common pest species, such as the lesser migratory grasshopper and the clearwing grasshopper. At the same time, climate change is disrupting the specialists’ life cycles and creating more of the hot, dry soil conditions compatible with generalist grasshopper egg-laying, resulting in yet more pasture-chomping grasshoppers.

“Last year, we had places where you couldn’t tell which pasture the cattle had been in and which pasture it hadn’t been in.”

Reukauf agreed that overgrazing can make grasshopper outbreaks worse. But he’s found that even when he leaves fields untouched by his cows for a season or two, the grasshoppers return in force. Three factors affect the outbreaks, he said: soil type, weather and cover.

“Last year, we had places where you couldn’t tell which pasture the cattle had been in and which pasture it hadn’t been in,” he said. “If the weather and soil type are against you long enough, the grasshoppers will win”— forcing ranchers to either truck in food or sell off cows. To avoid these heavy costs, some ranchers have asked the government for help.

“They need to be more transparent”

In June 2023, a member of the Xerces Society, an international nonprofit focused on invertebrate conservation, spotted a public notice from APHIS. Anticipating a bad grasshopper year, the agency planned to spray a pesticide over more than 24,000 acres of northern New Mexico.

Locals worried that the chemical, which turned out to be a neurotoxin called carbaryl, would kill pollinators like bees and butterflies and possibly end up in sensitive watersheds like the Rio Chama. Tribal members, recreational boaters, lawmakers and others erupted in protest, and the Bureau of Land Management Taos Field Office decided not to permit the spray on its land. Not long after the uproar, APHIS canceled the proposal.

The controversy drew local media attention, but even after activists filed information requests with APHIS, it remained unclear why the spraying had been planned in the first place. When asked, agency representatives told High Country News via email that APHIS only sprays if ranchers request treatment and if counts of certain pest grasshopper species exceed a set threshold. After the treatment proposed in New Mexico, the representative wrote, “several landowners and managers withdrew their requests for treatment.”

This lack of information concerns Terry Sloan (Diné and Hopi), the director of the nonprofit Southwest Native Cultures.

“They need to … give us information on the impact on monarchs, bees, pollinators, fowl, animals, the water life, all of that.”

“They need to be more transparent, letting us know what is happening and what chemicals will be used and give us information on the impact on monarchs, bees, pollinators, fowl, animals, the water life, all of that,” Sloan said.

The agency said it uses four chemicals to suppress grasshoppers: carbaryl, diflubenzuron, malathion and chlorantraniliprole. Carbaryl kills adult grasshoppers, while diflubenzuron kills young grasshoppers by preventing them from forming a new exoskeleton after they shed the old one. Diflubenzuron is generally considered environmentally safer than other insecticides, and APHIS — often in cooperation with counties, states, municipalities and individual landowners — sprays it on hundreds of thousands of acres each year. The harsher carbaryl is used less often.

Sharon Selvaggio of the Xerces Society, who worked with local activists to oppose the New Mexico spraying, worries that many of these pesticides are unnecessary. Diflubenzuron needs to be sprayed early in the season to be effective, so the decision to use it must be based on the previous year’s grasshopper counts combined with the current year’s juvenile numbers. But a large population of baby grasshoppers — many just millimeters long — doesn’t always reflect the number that will survive to do damage in adulthood.

“Like any insect, there’s always a lot more eggs and juveniles,” Selvaggio said. “You shouldn’t be putting insecticide over hundreds of thousands of acres of land without knowing if (the outbreak) will be bad.”

Looking for alternatives

Even ranchers beset by grasshopper outbreaks find that spraying isn’t always worth it. Lesh said that unless his timing is right, spraying accomplishes little and costs more than he wants to spend. Most years, he simply prays that enough rain falls to keep the soil wet and cool and yield plenty of grass for both insects and livestock.

Reukauf, however, has sprayed diflubenzuron three times in the last 24 years, coordinating with his neighbors to share the cost. Because federal assistance from the Farm Services Agency rarely covers the cost of treatment, ranchers and counties typically contract with APHIS to spray their rangeland in strips, alternating to cover a larger area and preserve some native grasshopper predators. Those treatments have helped reduce the outbreaks, Reukauf said.

Instead of spending money on chemicals, Selvaggio would like the government to consider compensating ranchers for income lost during bad grasshopper years, as it typically does after damaging hail or floods. Lightfoot said that land managers should also focus on improving rangeland health, which in turn would boost grasshoppers’ natural predators, including birds and other insects. More perennial grasses, which tend to increase with less grazing, would benefit forage and provide habitat for grasshoppers’ natural enemies — and that, he said will ultimately decrease the pesky insects.

APHIS representatives said that while the agency “does not have authority to work on other conservation measures,” such as working with ranchers to change management, it “routinely tests new products, formulations, and application methods to increase economic viability and reduce negative environmental impacts.”

Sloan, for his part, suggests that the federal government consult with tribes, which have dealt with grasshopper issues for millennia. “We are here to protect Mother Earth and her inhabitants,” Sloan said. “We have to be more responsible.”

This story is part of High Country News’ Conservation Beyond Boundaries project, which is supported by the BAND Foundation.

Christine Peterson lives in Laramie, Wyoming, and has covered science, the environment and outdoor recreation in Wyoming for more than a decade. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Outdoor Life and the Casper Star-Tribune, among others. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.