On 11 June, the Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS) announced that the Quest, the ship on which the famed Anglo Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton died, has been found in the Labrador Sea off the east coast of Canada.

The announcement was made by the RCGS’s chief executive John Geiger at the Memorial University’s Marine Institute in St John’s, Newfoundland. In an interview with The Art Newspaper, Geiger says that the six-years-in-the-making expedition to find the ship that sank in 1962—when it was owned by a Norwegian shipping company—almost came to a halt.

Plagued with technical issues, the expedition left St John’s on 5 June with a limited window of four days, two of which were lost to delays, according to Geiger. “We had challenges with equipment on the ship,” he says. “The hydraulic winch kept failing and we had to turn back at St Anthony’s for repairs.”

The 2024 Shackleton Quest Expedition team poses with the flag of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society on the deck of LeeWay Odyssey the morning after the find. Standing, left to right: Geir Kløver, Derek Lee, Jan Chojecki, John Geiger, Tore Topp, Katherine Smalley, Mark Pathy and Craig Bulger. Kneeling, left to right: Sarah Walsh, Martin Brooks, Antoine Normandin, David Mearns, Jill Heinerth and Alexandra Pope Photo: Jill Heinerth/Canadian Geographic

“We spent 17 hours ‘mowing the lawn’—going back and forth over the same area with sonar,” says Geiger, who admits to a mild obsession with the famed explorer, who died aboard the Quest in 1922 after suffering a heart attack. “But there was nothing of interest and I began to despair that it wouldn’t happen. I was almost ready to give up. But then I remembered Shackleton’s favourite phrase: ‘Patience, patience, patience.’”

Sure enough, at the 18th hour, “I saw there was something striking on screen. I knew then that that was it. It was very obviously Quest,” Geiger says. His passion project to find the Quest began several years ago, after he researched Shackleton’s explorations in the Canadian arctic. But it was news that a US explorer was also hot on the trail of the sunken ship that spurred him into action. Geiger began to plan the expedition in earnest last autumn.

Working with the blessing of the explorer’s grand-daughter, Alexandra Shackleton, who has been keeping her grandfather’s legacy alive through documentation and advocacy, plans came together in April, when Geiger attended the dedication of the Shackleton memorial at Westminster Abbey, officiated by the Princess Royal. That was when US “wreck-finder” David Mearns—known for finding some of the world’s the oldest and deepest shipwrecks—agreed to join the expedition after Alexandra introduced him to Geiger.

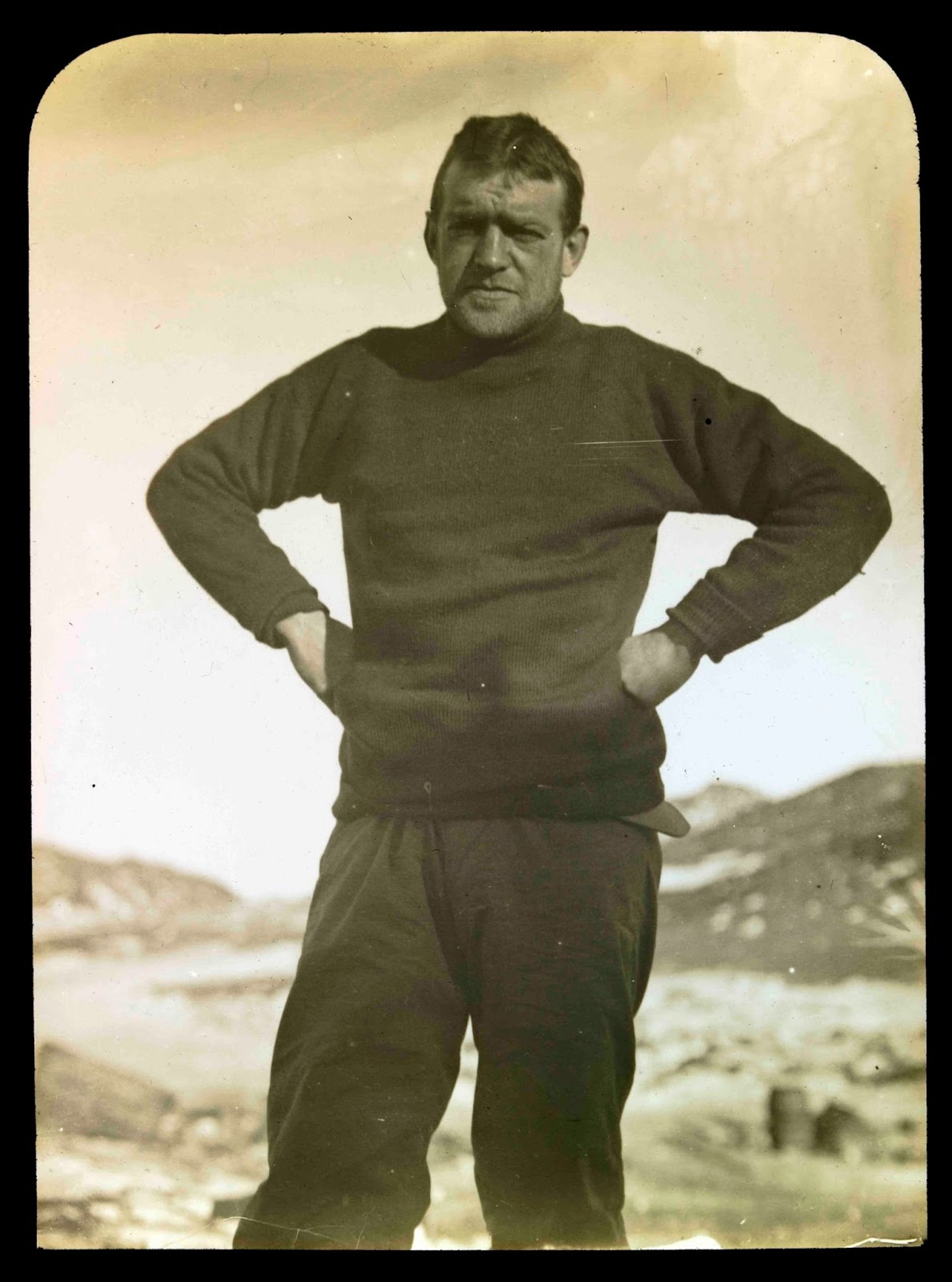

Ernest Shackleton in 1908 State Library of Victoria, via Wikimedia Commons

Geiger’s fascination with Shackleton, one of the last great explorers of the “heroic age”—before advanced technology and aircraft began to do what he calls the “heavy lifting”—was inspired by his “remarkable story”. “I was moved by the great humanity of the man and the poetry of his writing,” Geiger says. “He encapsulated the hero.”

He adds: “He had the patience and endurance that many other explorers of that era did not possess. He always put the safety of his crew ahead of his ego. While other explorers of the era often lost large numbers of men—he was exceptional in prioritising the well-being of his crew.”

When Geiger discovered Shackleton’s interest in Canada and his plans for an Arctic expedition, he became even more intrigued. Initially promised sponsorship by the Canadian government in 1921 for an Arctic voyage, with funding from the Eaton family, Shackleton abandoned these plans in favour of an Antarctic expedition when the Canadian prime minister at the time, Arthur Meighen, withdrew his sponsorship.

But the Quest was better suited for northern waters, not the rough seas of Antarctica. Shackleton, who was in ill health, suffered a heart attack during the journey. He died on 5 January 1922 aboard the Quest, off the coast of South Georgia Island, where he was buried. The ship continued to be used for various activities over the next four decades. During a seal hunt off the coast of Labrador in May 1962, the Quest struck ice and sank; the entire crew was rescued.

The Quest photographed as it slipped beneath the surface at 5:40pm on 5 May 1962 Courtesy Tore Topp

“There’s a Canadian stake in his story,” says Geiger, “and it seemed fitting that the RCGS should be involved in finding the lost ship.” The next steps include another expedition to document the largely intact ship with film and photography.

“There’s an amazing story to tell,” Geiger adds. He says he has plans for a possible book and exhibition at RCGS headquarters in Ottawa, where one about ocean conservation and exploration, Pressure: James Cameron Into the Abyss, has just opened.

The discovery of the Quest comes more than two years after the wreck of Shackleton’s most famous ship, the Endurance, was found 3,008 meters beneath the surface of the Weddell Sea.

Shackleton, Geiger says, who was knighted for his achievements by King Edward VII, was “one of the monumental figures of human history” Geiger adds, and there are “many more stories to tell”.